Table of Contents

- Introduction

- An unprecedented economic downturn—and rebound

- Potential signs of an equitable recovery

- Government focus has shifted to long-term priorities

- More options and leverage for workers

- Persistent inequality may eclipse recent progress

- Inflation has eaten away at wage growth

- Upward mobility is a steep climb

- Maximizing employment depends on a healthy care sector

- Remote work offers greater flexibility . . . for some

- Not a recovery, but a transformation

- Additional figure notes

We take a look at where California’s economy has been, where it might be headed, and how we can better insulate Californians against future upheavals.

The COVID-19 pandemic upended the status quo—changing how we work and where we live, snarling global supply chains, driving rapid price increases, and prompting massive government aid. After the initial shock of job losses, Californians are back to work and unemployment is low. But continued inflation, interest rate hikes, and a volatile stock market are raising concerns about an upcoming recession.

Ahead of the midterm elections, Californians say the economy, jobs, and inflation are the top issue facing the state. As residents try to make sense of the unsettling economic times we are living in, it’s no wonder many are uneasy. In a recent PPIC survey, seven in ten Californians say rising prices are causing them financial hardship, and less than a third say the US is going to have good times financially in the next year.

An unprecedented economic downturn—and rebound

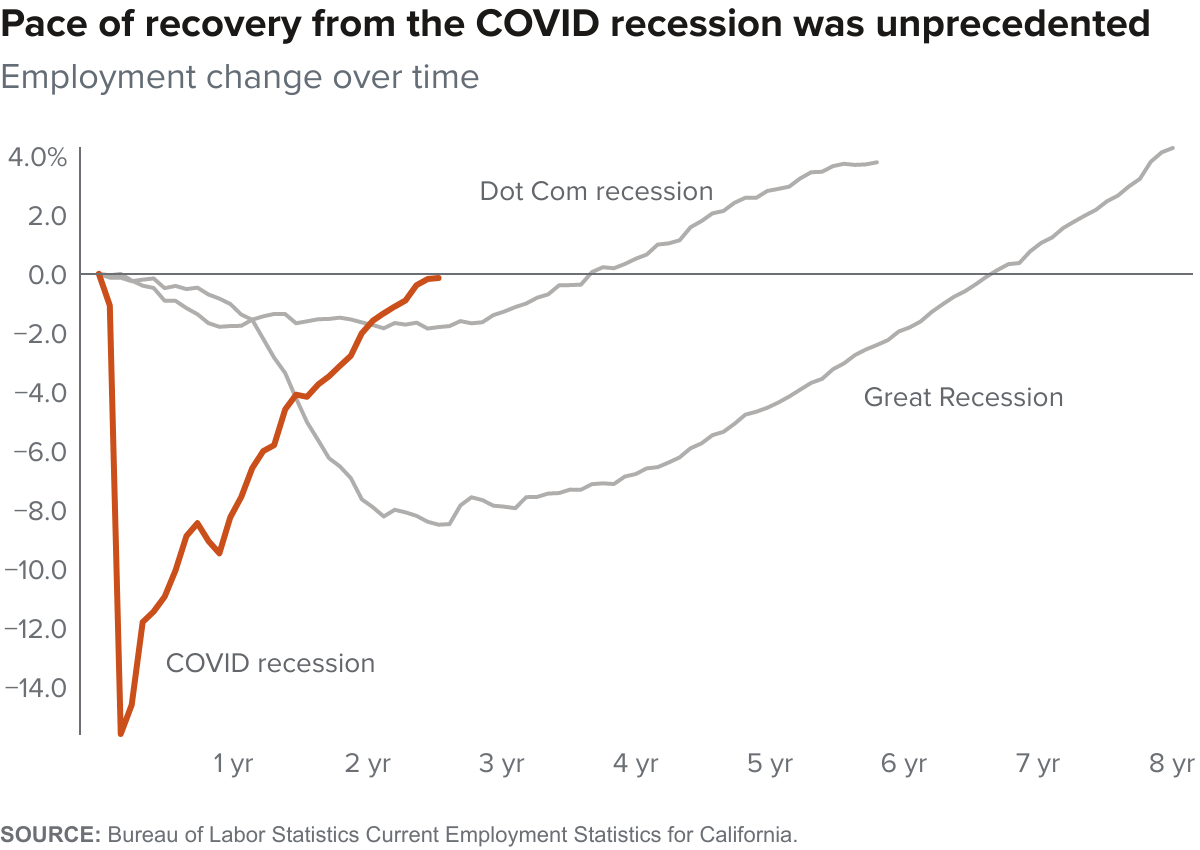

At the onset of the pandemic, business shutdowns led to sudden, severe employment losses, especially in face-to-face service jobs. But the pace of jobs recovery has also been incredibly quick—about twice as fast as the sluggish recovery that followed the Great Recession. In September, the unemployment rate (3.9%) was below pre-pandemic levels, though gains have been uneven across industries. Recovery in leisure, hospitality, and other service sectors has been slow, with jobs still down 7 percent compared to pre-pandemic times. Meanwhile, demand in transportation, warehousing, and utilities has been strong—employment is 16 percent higher than before the pandemic—and likely signals a long-term shift in the job market.

Potential signs of an equitable recovery

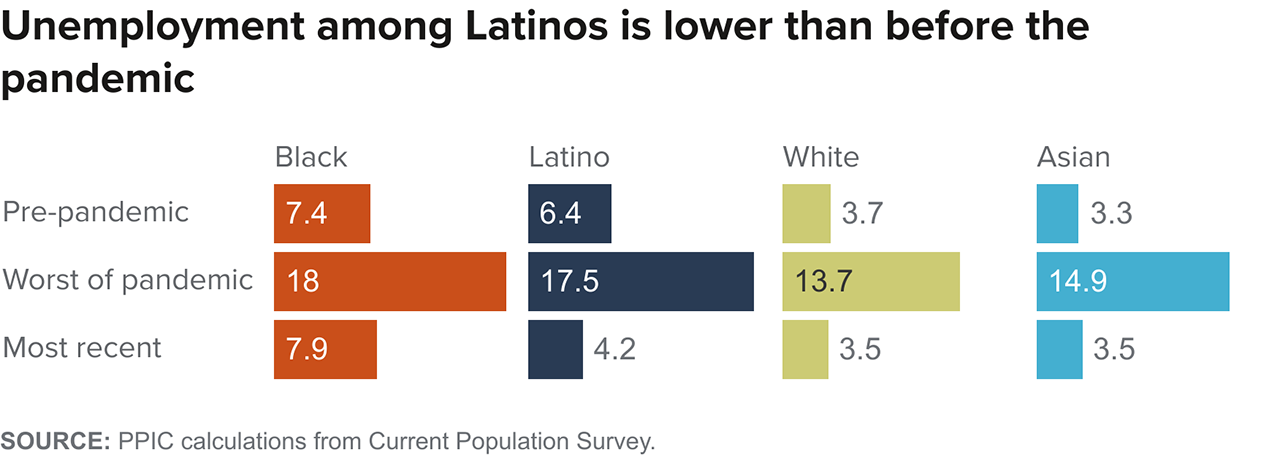

The speed of recovery is just one way the COVID recession broke the mold. Early on, it looked like we would see a repeat of past recessions, which have worsened inequality. But today, a couple of hopeful signs have surfaced: Unemployment rates across racial/ethnic groups are all nearing pre-pandemic levels, and notably, the unemployment rate among Latino Californians is lower than before the pandemic (4.2% vs. 6.4%). Regional gaps have also shrunk—inland areas with historically higher unemployment, including the Central Valley, central coast, and far north, are faring better than before. In fact, all the California metros in which current non-farm employment has surpassed pre-pandemic levels are inland.

This promising pattern is driven partly by sectors of work. For example, many Latinos work in construction and agriculture, sectors that have recovered quite well. However, a recent rise in Black unemployment (from a low of 6.5% in the first quarter to 7.9% in the third) could suggest equity concerns amid ongoing economic volatility. Moreover, employment is only one measure of economic well-being. It will take longer to determine if people are seeing improvements in earnings, hours worked, benefits, and other measures that more fully capture economic prosperity.

Government focus has shifted to long-term priorities

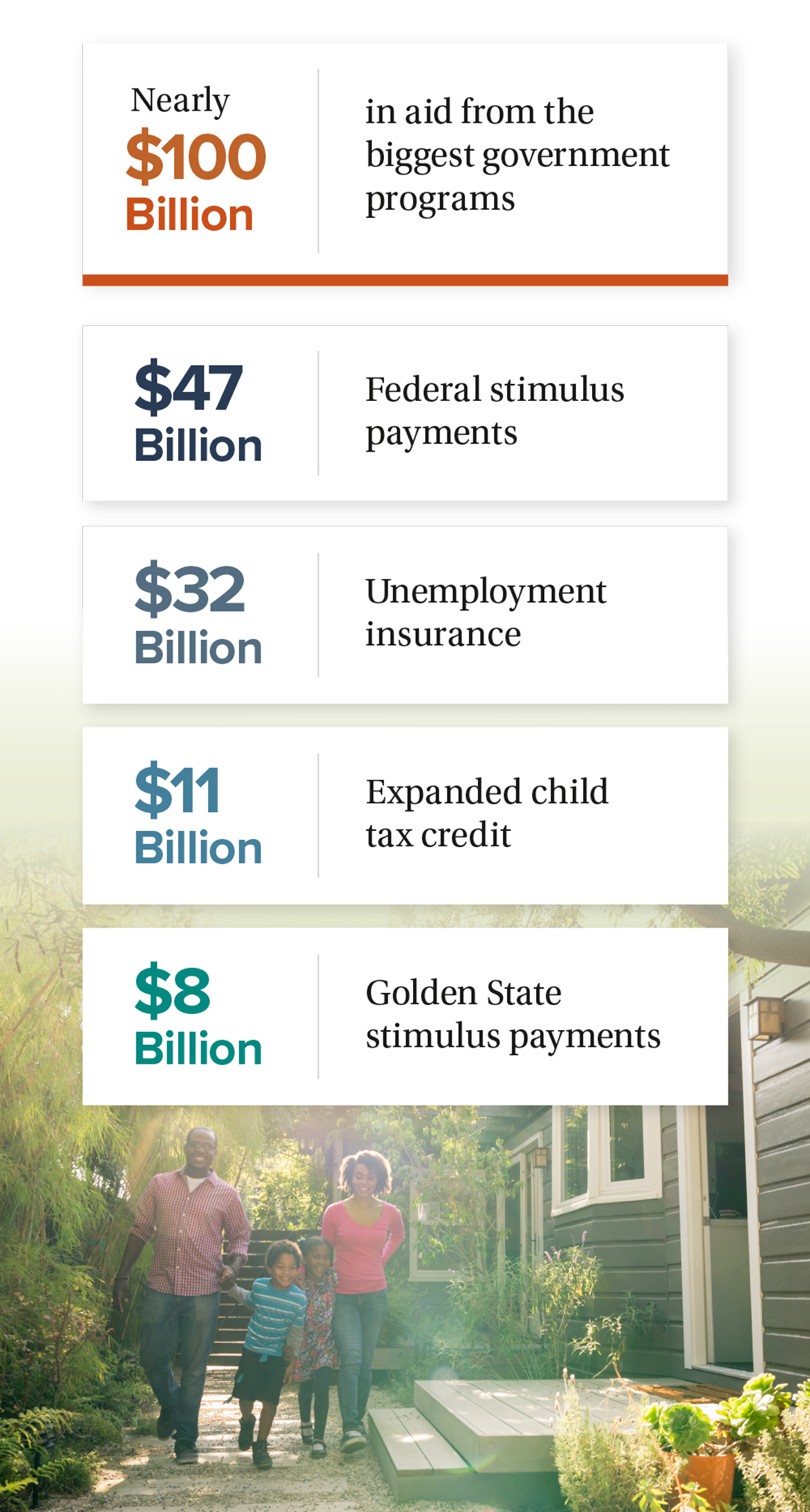

The US and California responded to the COVID crisis with massive aid to families and businesses, which lowered poverty and reduced income inequality—albeit temporarily. While this generous aid kept many families afloat, others were left out due to inequitable distribution, flaws in the unemployment insurance system, and limited eligibility for undocumented immigrants and their families. Now there are also questions about the extent to which aid buoyed consumer demand during a time of severe supply-chain bottlenecks, potentially fueling inflation. And employers have started paying back the debt from expanded unemployment benefits, further straining businesses as they struggle to hire and retain workers.

While some pandemic supports remain in place, new government investments have shifted to long-term priorities in infrastructure, regional economic development, and climate adaptation. These investments hold promise for supporting a robust future economy—if resources can be directed in efficient, effective, and equitable ways.

Pandemic aid to California families totaled nearly $100 billion

SOURCES: Census Bureau Supplemental Poverty Measure (2020 federal stimulus payments and unemployment insurance); IRS (2021 expanded child tax credit); California Franchise Tax Board (2021 Golden State Stimulus I and II).

More options and leverage for workers

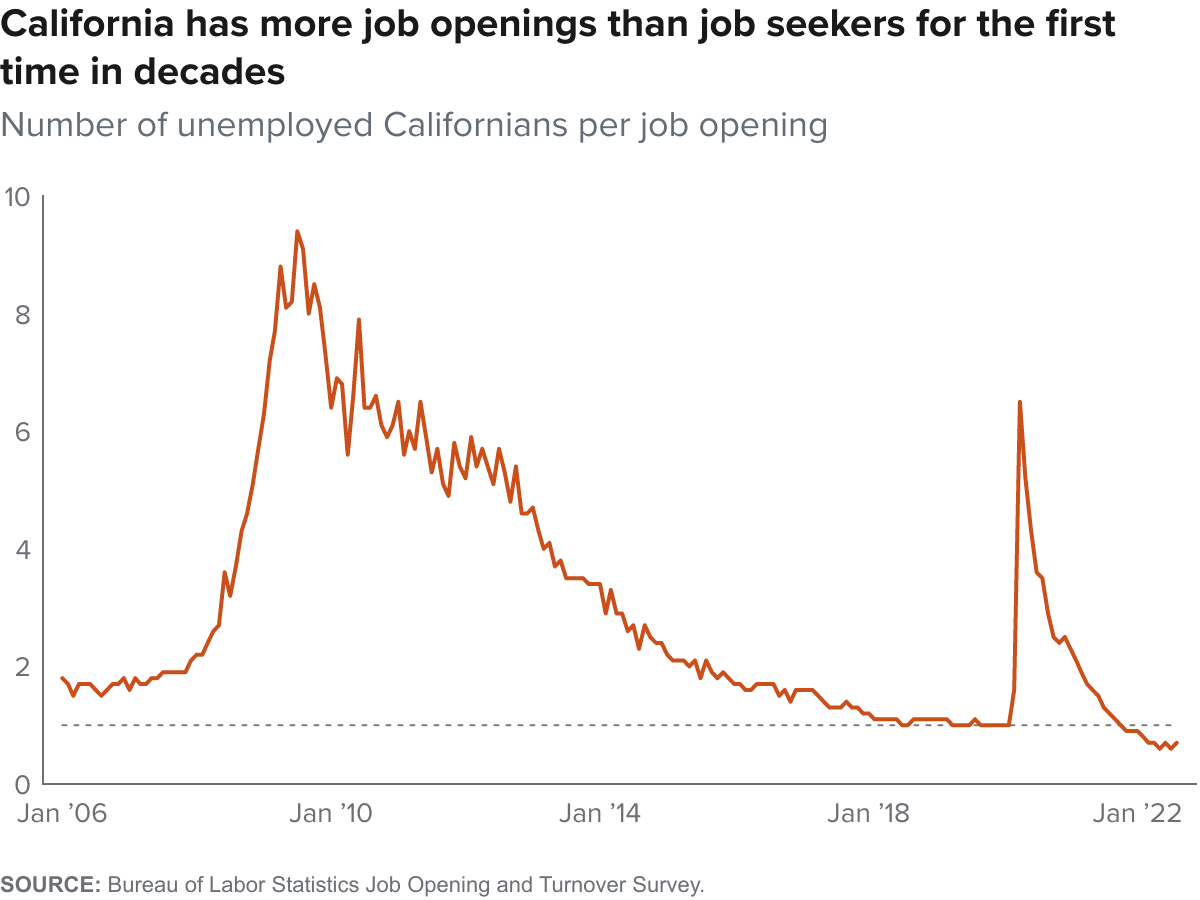

The Great Resignation gave way to the “Great Reshuffling,” as workers found new jobs and higher wages, especially in sectors like leisure and hospitality. For the first time in decades, California now has more job openings than job seekers. While this is good news for people looking for work, it also limits businesses’ workforce plans and growth—and wage increases have put upward pressure on prices.

Workforce participation has been gradually declining for decades, but it fell dramatically at the start of the pandemic. The strong job market has helped participation bounce back: the rate in September (62.3%) is nearly at pre-pandemic levels (62.8%), and some groups—including women, those ages 55–64, Latinos, and Asians—are participating at higher levels than before. However, white Californians and those with a high school diploma but no college degree have still not returned to prior levels of labor participation. In the face of long-term demographic factors like the aging population, a slowdown in immigration, and increased migration out of California, overall labor force participation may continue to stagnate. Policies that enable and encourage employment among all who are able to work will be critical to meeting the state’s workforce needs.

Persistent inequality may eclipse recent progress

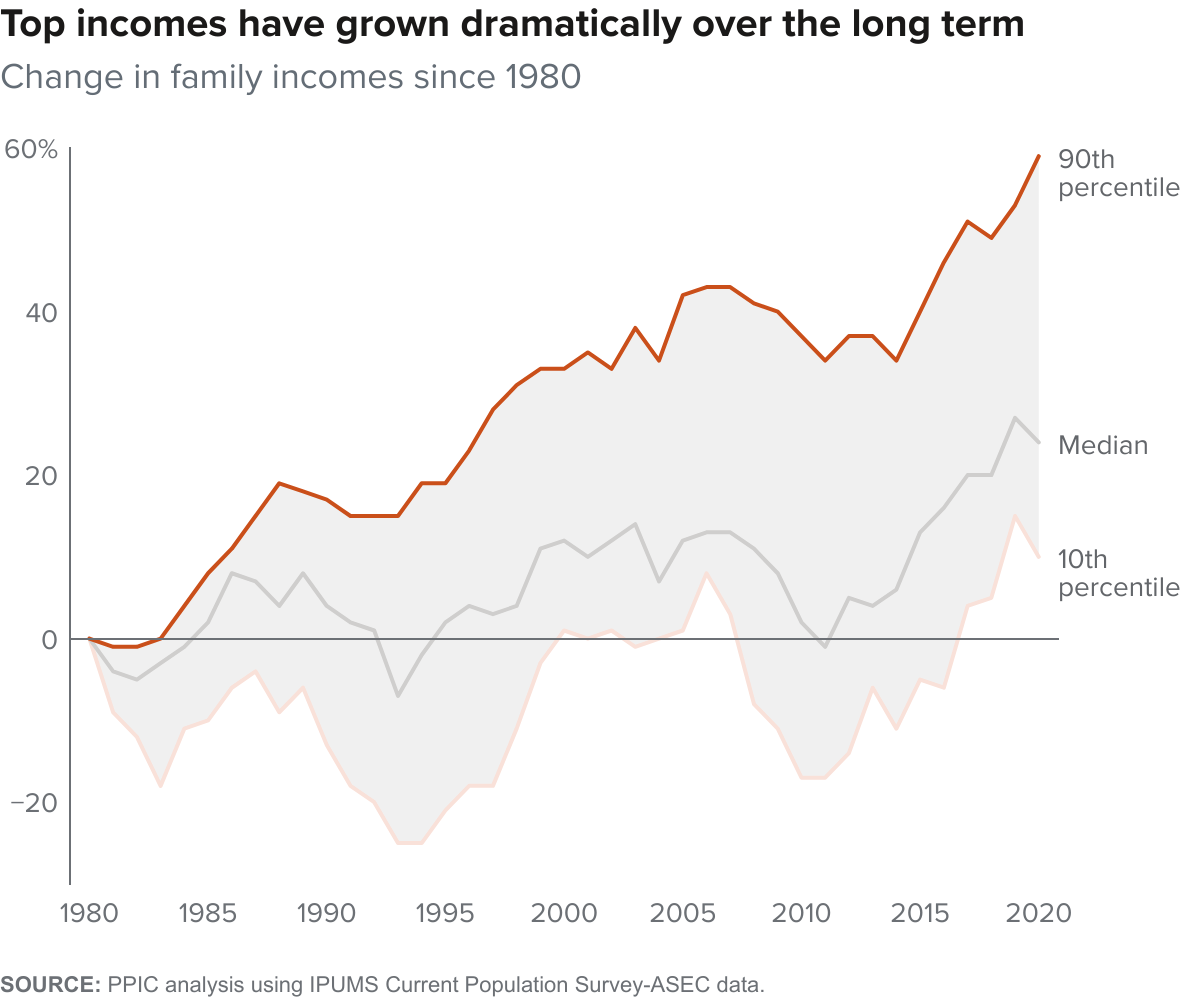

Good news about jobs and wages might just be a blip amid growing inequality over the long term. Driven by increased global trade, technological advancements that have favored more educated workers, and other factors, top incomes have grown 60 percent over the last 40 years (reaching $270,000 for families at the 90th percentile). Meanwhile, bottom incomes have suffered several large downward swings, only increasing about 10 percent ($25,000 at the 10th percentile).

Pandemic aid temporarily reduced income inequality, but fundamental economic trends suggest that growing income polarization is likely. In particular, increased automation and e-commerce may continue to shift job opportunities for workers with lower education levels. Through 2021, the rapid rebound of the stock market and soaring housing prices also benefitted wealthier individuals. More recent fluctuations in stocks and uncertainty with housing prices are disrupting gains that lower-income residents mostly never saw.

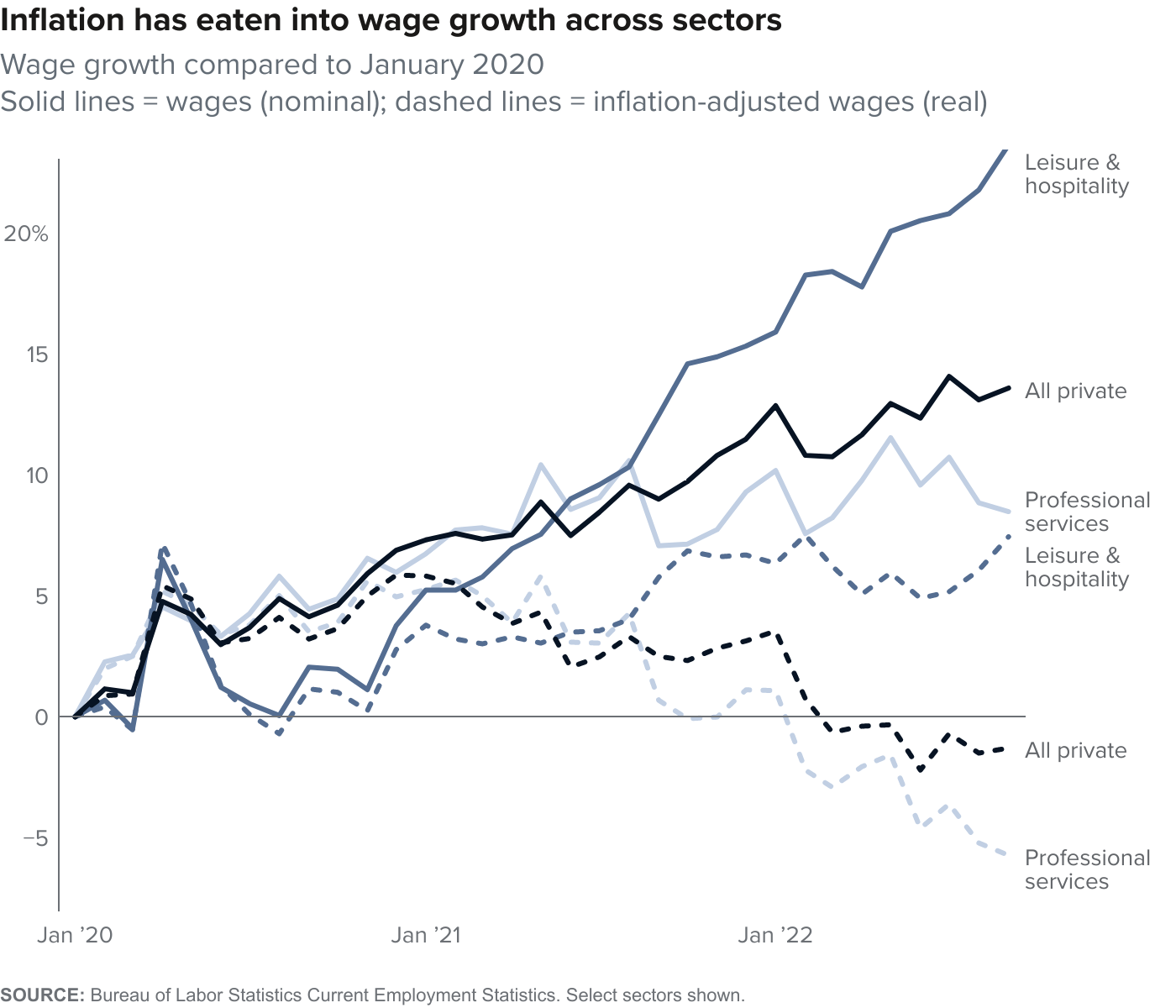

Inflation has eaten away at wage growth

Rising costs for food, housing, gas, and other goods and services continue to cut into Californians’ budgets. Wage increases provide a bit of a buffer, but in most sectors wages have not kept pace with inflation. Since the beginning of 2020, wages have increased 14 percent for all private-sector workers, but after adjusting for inflation, they are down 1.3 percent. Only two of the largest sectors have shown growth in inflation-adjusted wages: leisure and hospitality (up 7%), and trade, transportation, and utilities (up 1%; not shown in chart). However, these are traditionally lower-wage sectors, so even with this growth many workers may still face difficulties meeting their basic needs.

Recessions can often follow on the heels of inflation. To control inflation, the US Federal Reserve raises interest rates and takes other actions that constrict the economy, potentially increasing unemployment and the risk of recession. Achieving a “soft landing” is difficult. The most generous assessments suggest that in half of previous inflationary episodes the Federal Reserve managed to tame inflation without an ensuing recession. Furthermore, while the benefits of reduced inflation will be broadly felt, the potential income and employment impacts of a recession may be uneven; in most recessions, low-income, Black, and Latino workers fare worse.

Upward mobility is a steep climb

High income inequality in California coincides with high levels of poverty and stagnant upward mobility. About 6.3 million Californians cannot meet their basic needs and it has gotten harder to climb the economic ladder over time. Sky-high housing costs have left many—especially younger, lower-income, and nonwhite residents—without the meaningful opportunity to own a home, a vital path to wealth creation for earlier generations. And in our increasingly knowledge-based economy, a college degree is key to economic mobility, but college affordability and debt are limiting the viability of this pathway for those who might benefit the most.

Pathways to economic success are constrained

SOURCES: Chetty et al. (2017); PPIC calculations using 1960 Census, 2020 Current Population Survey-ASEC, and 2020 American Community Survey data accessed via IPUMS.

Maximizing employment depends on a healthy care sector

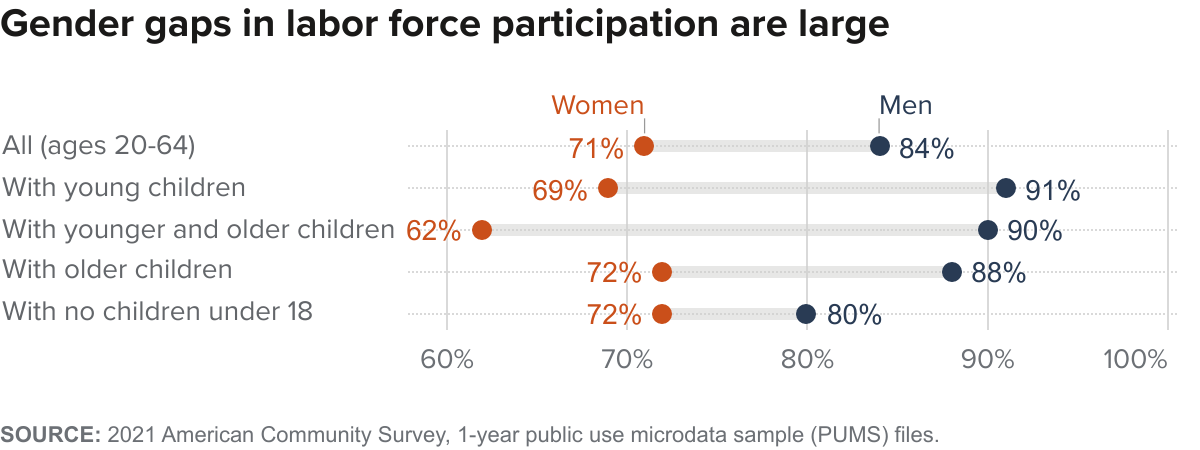

COVID shined a stark light on women’s vulnerability in the workplace. During the height of the crisis, unemployment among women rose much higher than it did for men, and women were more likely to leave the labor force—the result of the overrepresentation of women, especially women of color, in hard-hit service jobs and frontline work, as well as women choosing to leave their jobs when confronted with increased health risks and school closures.

Today, overall labor force participation rates for women—including women with children—are actually above pre-pandemic levels. But gaps between men and women are still large, especially for women with children in the household; notable disparities also exist between women with and without college degrees. If current trends in women’s employment persist, levels will likely fall short of what the labor market needs over the long term. Supporting families’ child care and elder care needs—including addressing the precarity of work in this sector—would help relieve a significant constraint on employment that disproportionately affects women.

Remote work offers greater flexibility . . . for some

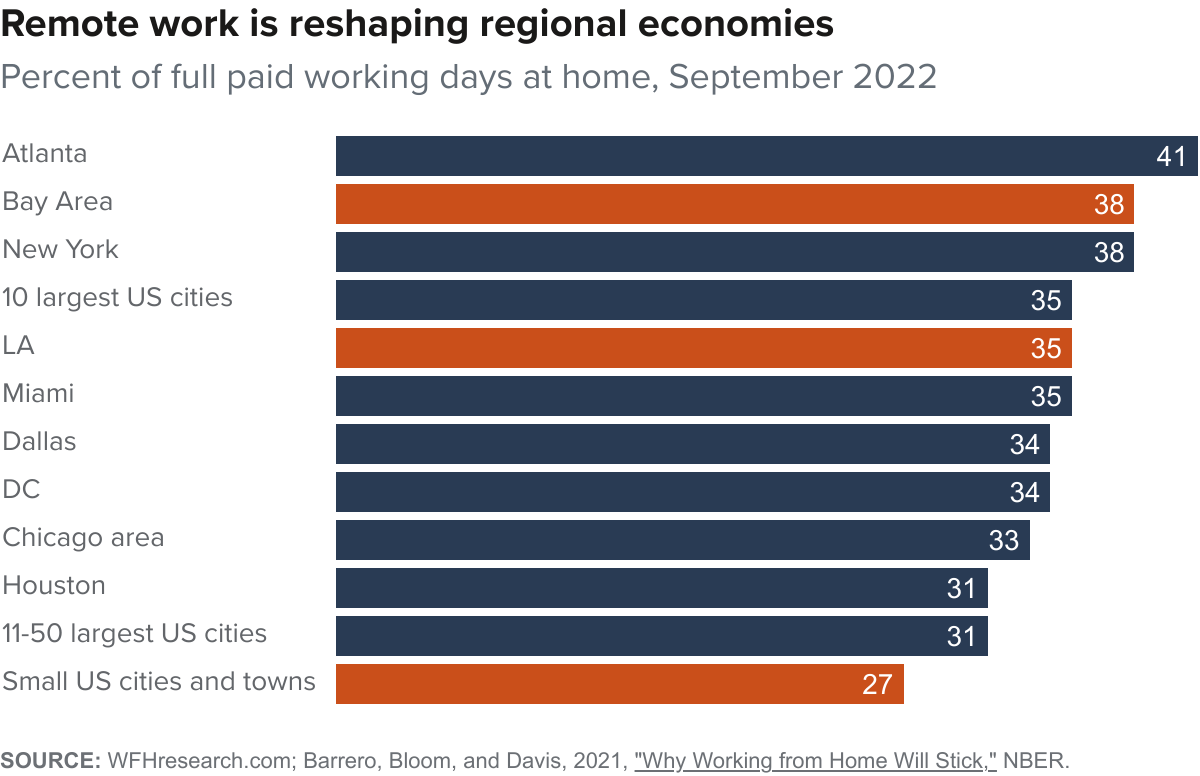

We are in a period of “Great Experimentation” in remote work, which may further polarize economic opportunity. Pre-pandemic, about 5 percent of working days were spent at home—this shot up to 60 percent when COVID hit. In some sectors, especially those that skew toward well-educated workers in higher-paying jobs and industries such as information and finance, remote work is common. In lower-wage sectors such as food services, transportation, and retail, it is rare.

Remote work may also trigger shifts in economic inequality within and between regions. Today, the share of work-from-home days is 35 percent in Los Angeles and 38 percent in the Bay Area (about two days per week). Nationwide, remote work is more prevalent in large metro areas than smaller cities and towns. As higher-wage workers move away from places with higher costs of living, these changing migration patterns are reshaping regions. Urban areas must figure out new ways to sustain healthy downtown economies; elsewhere, population surges are providing a boost to local economies but also placing new demands on physical and social infrastructure.

Not a recovery, but a transformation

For all the turmoil of the past few years, California’s economy remains remarkably strong and dynamic. The state continues to be dominant in diverse industries, including technology, trade, finance, tourism, entertainment, and agriculture, which have helped drive its recovery. California’s world-class universities, highly educated workforce, and wealth also undergird its position as a longstanding leader in research, innovation, and entrepreneurship.

We are living in a unique time. Historical patterns that have shaped our economy in previous eras may not hold. And those past patterns and policies produced the gaping economic inequality that currently pervades California’s regions and populations.

Now is the time to chart a new path forward. The unexpected transitions brought by the pandemic, as well as those long predicted due to a changing climate, exorbitant housing costs, and technological developments, are daunting. But they also offer a distinct opportunity to leverage California’s many assets and transform our approach to the economy and economic well-being.

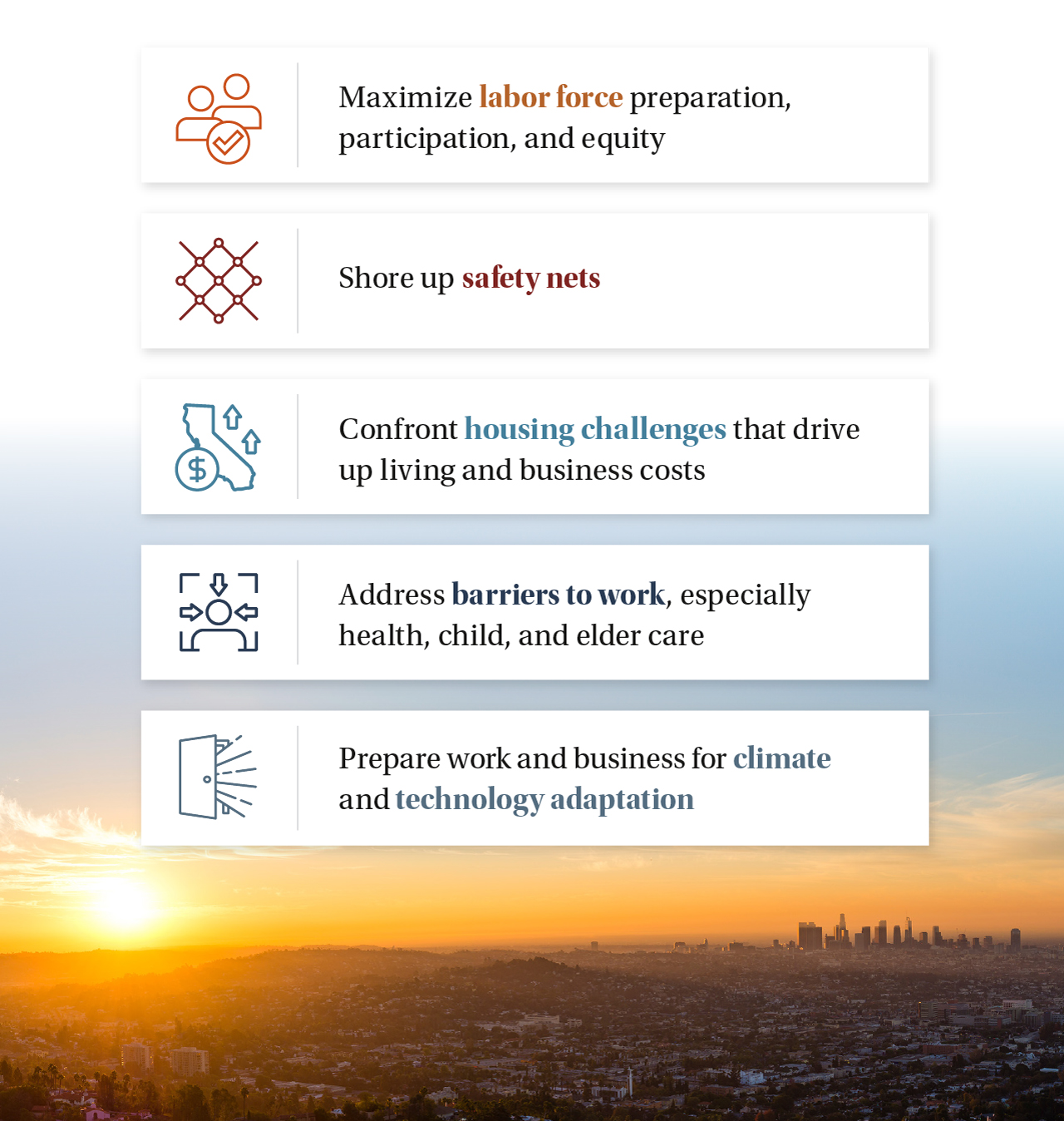

Strengthening the ecosystem that enables businesses to create jobs—and that helps Californians prepare for and access jobs—is an essential piece of the puzzle. Key features of this ecosystem include: equitable access to training and education, a strong safety net for those facing unforeseen disruptions, housing conditions that allow for the state’s people and businesses to move and grow, and reliable and affordable access to health, child, and elder care. This ecosystem must also foster a nimble business environment that allows businesses to remain competitive amid rapid changes in our climate reality, technology, and an increasingly global economy.

Bolstering the state’s economic foundations and eliminating barriers to economic opportunity would open up the California Dream and ensure that more people can participate in and benefit from the state’s economic prosperity.

Preparing California for an uncertain future

Topics

COVID-19 Economy Health & Safety Net Housing Poverty & InequalityLearn More

A Regional Look at the Availability of Well-Paying Jobs after COVID

As the COVID Emergency Ends, a Look at the Pandemic’s Economic Impact

A Tight Labor Market: Challenges for Business, Opportunities for Workers?

How Is Remote Work Affecting Worker Preferences and the Economy?

Shifting Gender Employment Patterns and California’s Care Sector