Table of Contents

- Key Takeaways

- Introduction

- The Pandemic and the Implementation of AB 705 in ESL

- A Portrait of Degree-Intending English Learners at CCCs

- How Have ESL Placement Policies Evolved under AB 705?

- How Are Colleges Structuring ESL Sequences under AB 705?

- Enrollment and Outcomes for Degree-Intending ESL Students

- Conclusion and Recommendations

- Notes and References

- Authors and Acknowledgments

- PPIC Board of Directors

- Copyright

Key Takeaways

California’s community colleges began implementing Assembly Bill 705 (AB 705) reforms for credit English as a Second Language (ESL) in fall 2021, two years after implementing similar reforms in English and math. With a broad goal of improving success and equity for students pursuing degrees and transfers to four-year colleges, AB 705 reforms are already making notable transformations to ESL placement policies and the ESL courses into which English Learners (ELs) are placed. Building on our previous research, this study reports on the progress colleges have made in implementing AB 705 in ESL across the community college system.

- Colleges implemented AB 705 reforms to ESL despite the challenges created by COVID-19. By fall 2021, many colleges had moved away from standardized placement tests (30%) and toward guided placement (79%), engaging students more actively in the placement process. →

- Colleges have made great strides in shortening their ESL course sequences. In 2021, over half of colleges offered sequences of four levels or less, compared to just under one-third in 2016. AB 705 distinguishes ESL from remediation in English; this recognition that ESL students are foreign-language learners seeking proficiency in an additional language has allowed for growth in transferrable ESL courses for general education credit, including ESL equivalents of college composition. →

- Variation across colleges in placement policies and ESL sequences could potentially undercut equitable access and success—it means that an English Learner’s likelihood of enrolling in or completing college composition may depend on which college that EL attends. →

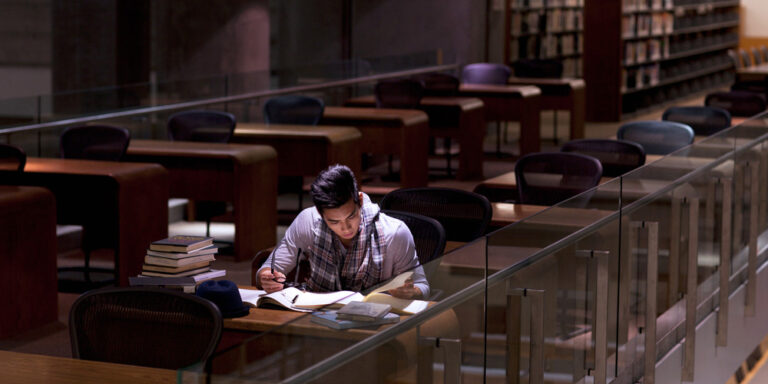

- Colleges are now required to place ELs who are US high school graduates in college composition. Since some of these ELs may need language support, a growing number of colleges are offering a transfer-level English ESL-equivalent course (TLE-ESL), a TLE designed for multilingual speakers, or ESL corequisite support for TLE. So far, success rates in those courses are higher than rates in traditional TLE offered in English departments; they are above 70 percent regardless of race/ethnicity, gender, or age. These findings suggest that colleges should continue to expand access to and support in college composition for ELs. It will be important to monitor the effectiveness of these courses as they become more prevalent. →

- Given the growing number of ESL courses that are transferrable, colleges have opportunities to connect ESL with Guided Pathways, the College and Career Access Pathways (CCAP), and the Vision for Success. This would help boost enrollments while also improving the pathway for EL students from high school to college and beyond. →

- Given AB 705’s three-year timeframe for EL students’ completion of transfer-level English or the ESL equivalent, it is too early to assess the effects of ESL reform on this key outcome. And because implementation has occurred during the pandemic, the changes in enrollment and outcomes that we observe cannot be solely attributed to AB 705. →

Introduction

Every year, tens of thousands of English Learners (ELs) with a range of goals, citizenship statuses, and educational backgrounds enroll in English as a second language (ESL) coursework at the one of 115 California Community Colleges (CCCs). Some intend to improve their English language skills or their job or career prospects. Others enroll with the goal of obtaining a college degree or certificate, or transferring to a four-year university. Moreover, some of these students take ESL courses in community college after graduating from a US high school, while others have completed various levels of education (ranging from primary school to graduate education) in their home countries. Undoubtedly, the range of educational backgrounds and motivations make it challenging to serve this population.

The CCCs educate a large number of ELs—more than either of the state’s other two higher education systems. English proficiency is related to economic mobility, access to high-wage jobs, lower levels of unemployment and underemployment, and greater productivity (Wilson 2014). And California’s future is tied to the success of ELs, since 19 percent of K–12 students are ELs. While California has the fifth-largest economy in the world, its level of income inequality is among the highest in the US, and more than a third of its population lives in or near poverty (Bohn and Thorman 2021; Bohn, Danielson, and Malagon 2021). Given the need for more college graduates in the coming years, the returns to a college degree, and the strength of the current labor market, the CCC system has a unique opportunity to help ELs (and their families) achieve social and economic mobility. Therefore, it is important to understand how California’s community colleges are serving ELs who enroll in ESL courses with the goal of obtaining a degree or transferring to a four-year college.

For this group of degree- or transfer-seeking students, ESL courses are one of the primary pathways to college success (Rodriguez et al. 2016; Raufman et al. 2019). Research has found ample room for improvement in these pathways. First, colleges in California and across the country have historically relied on standardized tests to place students into lengthy and complex ESL sequences (Bunch et al. 2011; Hodara 2015; Rodriguez et al. 2016; Rutschow and Mayer 2018; Willett 2017). Research has indicated that ESL placement tests should not be the primary determinant for placement because they often provide an incomplete understanding of a student’s English language and literacy skills (Bunch et al. 2011; Kokhan 2013; Li 2021; Llosa and Bunch 2011). Second, there is evidence that lengthy developmental English and ESL sequences significantly reduce students’ chances of completing gateway English courses (Bailey et al. 2010; Cuellar Mejia et al. 2016; Rodriguez et al. 2019).

Partly in response to this research, Assembly Bill 705 (AB 705 Irwin) sought to increase successful completion of transfer-level math and English courses by addressing systemic problems in traditional placement policies and curricular structures. The law requires colleges to maximize the probability that students who enroll in credit ESL courses complete transfer-level English within three years. It also requires community colleges to use high school records as the primary criteria for placement and provides flexibility for colleges to use guided or self-placement if high school records are not accessible. Notably, the bill acknowledges that ESL is distinct from remediation in English and that students enrolled in ESL credit coursework are foreign-language learners seeking proficiency in an additional language.

Systemwide, ESL reform was scheduled to be implemented in fall 2020, one year after similar reforms were enacted in math and English (California Community Colleges Chancellor’s Office 2018). However, the advent of the COVID-19 pandemic in spring 2020 delayed ESL implementation by a full year (Lowe and Davidson 2021). Practitioners, researchers, ESL faculty and department chairs, and other stakeholders agree that it will be extremely difficult to disentangle the impact of AB 705 on ESL course enrollment and successful completion from the effects of the pandemic. During this period, colleges, faculty, and students faced unimaginable challenges due to the public health crisis and the shelter-in-place orders (see Text Box). While it is important to keep in mind the different ways the pandemic disrupted the implementation of AB 705 for ESL, an examination of the way AB 705 efforts played out during the first year can inform and improve its ongoing implementation. As we will see throughout this report, AB 705 did lead to remarkable changes to placement and credit ESL curricular structures, and existing research suggests these changes will likely have a lasting impact on the outcomes of English Learners statewide. More recently, follow-up legislation, known as Assembly Bill 1705 (AB 1705), has been signed into law with the aim of clarifying AB 705 requirements (see Text Box).

This report builds on our previous research on ESL in California Community Colleges (Rodriguez et al. 2019) by shedding light on the progress colleges have made toward implementing AB 705 across the CCC system in fall 2021. To better understand the changes that colleges across the state have made to their ESL placement policies and curricular structures in response to the law, this report uses qualitative and quantitative data:

- To identify how colleges modified placement systems and ESL course offerings during the first year of implementation, we have drawn information from college websites and documents, including college catalogs and course schedules, as well as the AB 705 adoption plans submitted to the CCC Chancellor’s Office (CCCCO).

- We used student-level data from all 115 colleges to conduct a descriptive examination of ESL and transfer-level English or ESL equivalent course enrollment and successful completion in fall 2021.

- We conducted interviews with ESL faculty and department chairs at 16 colleges across the state to better understand the challenges and opportunities created by AB 705 and the pandemic. These colleges are representative of the different types of placement and curricular reforms as well as regions of the state.

Importantly, across all these areas we pay special attention to how the pandemic affected implementation efforts.

Our work is well-timed to provide early insights to policymakers, researchers, and practitioners on the role of AB 705 in addressing equity gaps for ESL students, and well-positioned to inform and improve reform efforts in California and nationally.

The Pandemic and the Implementation of AB 705 in ESL

In this section, we draw on insights from our interviews with ESL faculty and department chairs to highlight several ways the pandemic disrupted AB 705 implementation and affected ESL students as well as ESL departments and faculty.

The Pandemic Disrupted AB 705 Implementation

The delay in official implementation until fall 2021 gave colleges more time to prepare, but the planning that had been done on the placement and curricular front had to be rapidly moved online in response to the COVID-19 pandemic (Lowe 2020; California Community Colleges Chancellor’s Office 2018).

Therefore, at a time when many colleges were planning to offer new ESL courses for the first time, they had to shift them online. Many colleges—and all of the colleges involved in our interviews—had never offered ESL courses fully online, and most instructors did not have training or experience in teaching remotely. While professional development helped ease this transition, all faculty and department chairs we spoke to indicated that this disruption to teaching and learning posed challenges for both students and faculty. A silver lining of the pandemic, however, was that it brought forth important opportunities to expand ESL access via effective and well-supported online learning. All of our interviewees indicated that online learning would continue to be an option. Interviewees noted that online learning expands access to populations in need of more scheduling flexibility. Still, given the mixed evidence on the effectiveness of online learning for underserved populations, it will be critical for colleges to ensure that courses are accessible, effective, equitable, and supported.

While standardized placement tests had been eliminated in math and English as of fall 2019, many ESL programs relied on approved ESL assessment tests administered at on-campus testing centers to determine placements. But the challenge of designing and launching fully remote assessment and placement systems in spring 2020 accelerated the movement away from the tests. In California, and in other states and systems, most colleges adopted guided and/or self-placement methods that relied on students’ self-reported information (Brathwaite et al. 2022; Morton 2022; Cuellar Mejia et al. 2020). All ESL stakeholders we interviewed agreed that while the move to online or remote placement was not easy, and it is still not perfect, continuing to build on and improve this new method brings with it the opportunity to make the process and courses more accessible.

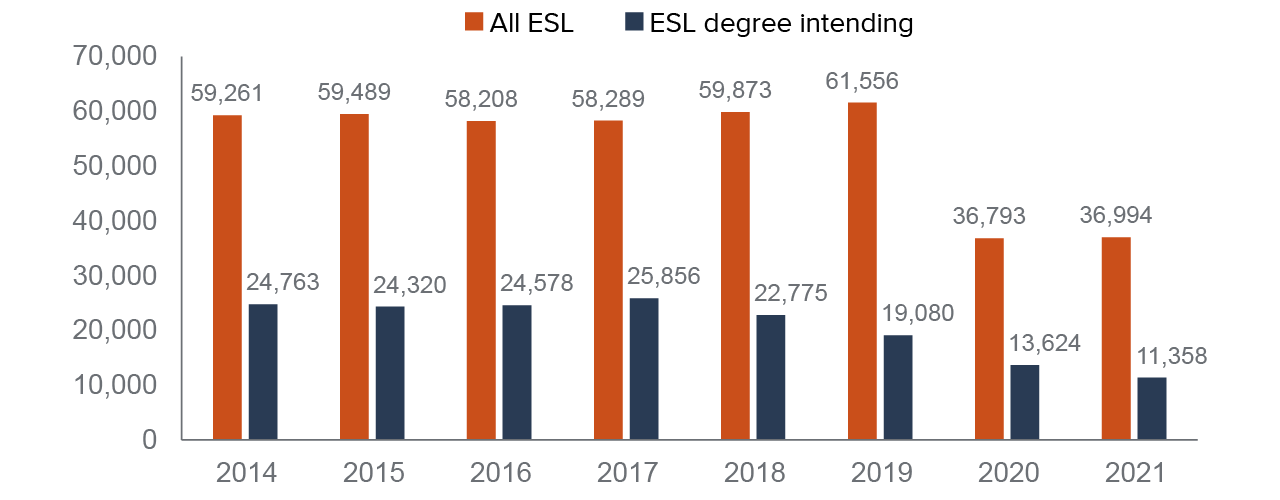

Severe enrollment declines induced by the COVID-19 pandemic have been widely documented at California’s community colleges (Bulman and Fairlie 2022; Perez et al. 2022). Very early on, it became clear that the statewide shelter-in-place order along with the health impacts of COVID-19 would have a disproportionate impact on low-income communities and people of color, the populations most likely to enroll in community college. Unsurprisingly, ESL enrollments experienced steep declines in fall 2020 that have persisted ever since (Figure 1). Moreover, ESL faculty and department chairs also shared that the political climate on immigration prior to and during the pandemic coupled with COVID travel restrictions, which strictly limited or cut off travel from certain countries, also affected the ability of international students, a key part of many colleges’ ESL populations, to enroll. Indeed, our data show that between fall 2019 and fall 2020, overall enrollment in ESL among student visa holders declined 55 percent, compared to 41 percent for ESL overall.

Our ESL faculty and department chair interviewees noted that AB 705-induced enrollment declines were expected given that the law now required that all US high school graduates be placed into college composition. Additionally, lower enrollments were also expected at many colleges that had reduced sequence lengths to be compliant with AB 705’s goal that student placement maximize the likelihood that ELs complete college composition within three years. These declines in enrollment have affected the student composition but it will be nearly impossible to disentangle the enrollment effects of the pandemic versus AB 705. As a result, interviewees concurred that the interpretation of course enrollment, success, and equity data will always require an asterisk for this period and cannot be attributed to AB 705.

The number of ESL students declined steeply during the pandemic

SOURCE: Author calculations from Chancellor’s Office MIS data.

NOTES: Fall of each year. Degree-intending ESL students are identified using ESL students’ self-reported goals.

The Pandemic Took a Toll on ESL Students and Faculty

In our interviews with ESL faculty and department chairs, we asked them to describe the pandemic’s impact on their students and themselves.

Physical and mental health and economic concerns were highlighted in our conversations. Faculty recounted their frustration about the lack of in-person engagement with students, which made it challenging to check in and provide educational and sometimes emotional support. One faculty member recounted that mental health strain and loneliness were factors for her students, especially international students, and that she “tried to keep class as a space for hope. … For some, this was all they had.” Educational and resource assistance services were either not provided or were reduced after campuses closed their physical doors. For example, on one campus, the free food pantry that had been open seven days a week before the pandemic was open just one day as a drive-through. Educational resources, such as language labs, did not operate as they had before, and libraries were closed. And community-building events such as graduations and ESL fairs were put on hold.

At the beginning of the pandemic, many students withdrew from school because they were homeschooling their children, providing child care or elderly care, and/or had lost work; later in the pandemic, students withdrew or did not enroll because they were working too many shifts. Faculty reported that ESL students, often employed as essential workers, had less time for school once their jobs reappeared, either due to pressure from employers or to make up for lost wages.

Technology was another major issue. Not all students had sufficient access to devices, software, internet bandwidth, or the technological skills early in the pandemic to make the shift to online education. Although community colleges quickly worked to provide students with access, and online education provided new opportunities for some ESL students to fit schooling into their schedules, faculty said there were tradeoffs. The increased flexibility of online instruction allowed employed students to take classes during breaks in shift work (e.g., in the fields or retail). But some students struggled with the online school platforms, and remote instruction was often interrupted by home life—for example, young children in the background of a Zoom class session or family members providing too much help with assignments.

Faculty found it challenging to adapt to online learning—they grappled with technological issues and major shifts in teaching and connecting with students. Placement processes had to be moved online while ESL faculty were trying to plan for AB 705-induced changes to placement policies. After a struggle to ensure that all ESL faculty had the necessary home technology, online classroom management tools (e.g., Canvas), and techniques for teaching online, by fall 2020 there was a bit more of a rhythm to ESL instruction. However, not all faculty made the transition: some retired early. Some respondents mentioned the particular challenges for part-time faculty, who earn much less and were less likely to own the necessary equipment and connections required for online teaching.

While many faculty talked about their bouts with and concerns about COVID and their mental health struggles, our conversations were especially focused on the fatigue they experienced. Sources of fatigue included the non-stop effort to transition online and the continued strain of running classrooms (whether in person or on Zoom) with students who had protracted absences due to COVID and evolving concerns about variants. The challenges of online instruction—organizing group work, for example—also came up repeatedly. Faculty also talked about isolation being hard on them personally, and remote work making it more difficult to connect with colleagues about students who were struggling or who might benefit from a different course placement.

Now that they have both in-person and online options, some faculty have expressed clear preferences. Some will only teach in-person sections. But many others were surprised to find that online learning had many benefits, for both their students and themselves. On at least one campus, where a certain percentage of courses must be offered in-person, the ESL department chair noted that it was a challenge to find enough instructors willing to teach on campus.

A Portrait of Degree-Intending English Learners at CCCs

This report focuses on EL students who intend to continue their community college education beyond ESL coursework. We identify these students as “degree-intending” based on their declared intent to pursue a degree or transfer to a four-year college. This group is the main population of interest for AB 705 reforms.

Among all community college students enrolling in fall 2021, 68 percent of students declared an intent to pursue a college degree and/or transfer. Given the wide range of motivations for learning English at a CCC, it is perhaps unsurprising that a much lower share of the ESL population—only about one-third—declared this goal. The decline in the number of degree-intending ESL students accelerated during the pandemic, along with the decline in the overall ESL population (Figure 1 and Technical Appendix Figure C3).

Degree-intending ESL students are more likely to be female than male (67% versus 32%); female students are similarly overrepresented among ESL students overall (71% versus 27%). The female-to-male ratio was increasing among ESL students before the pandemic (Technical Appendix Figure C4).

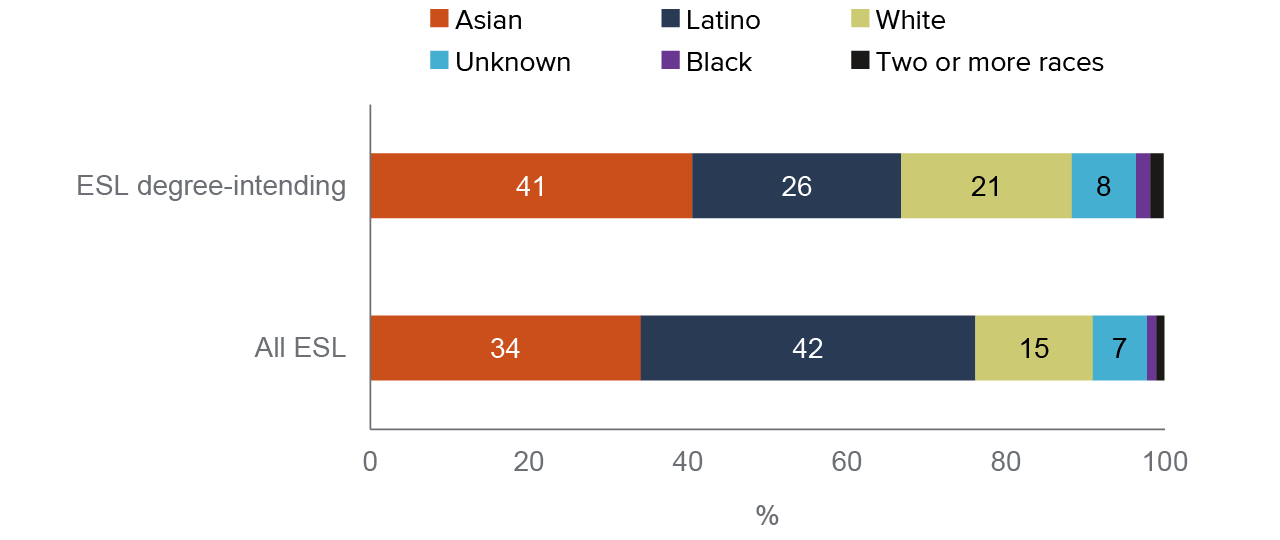

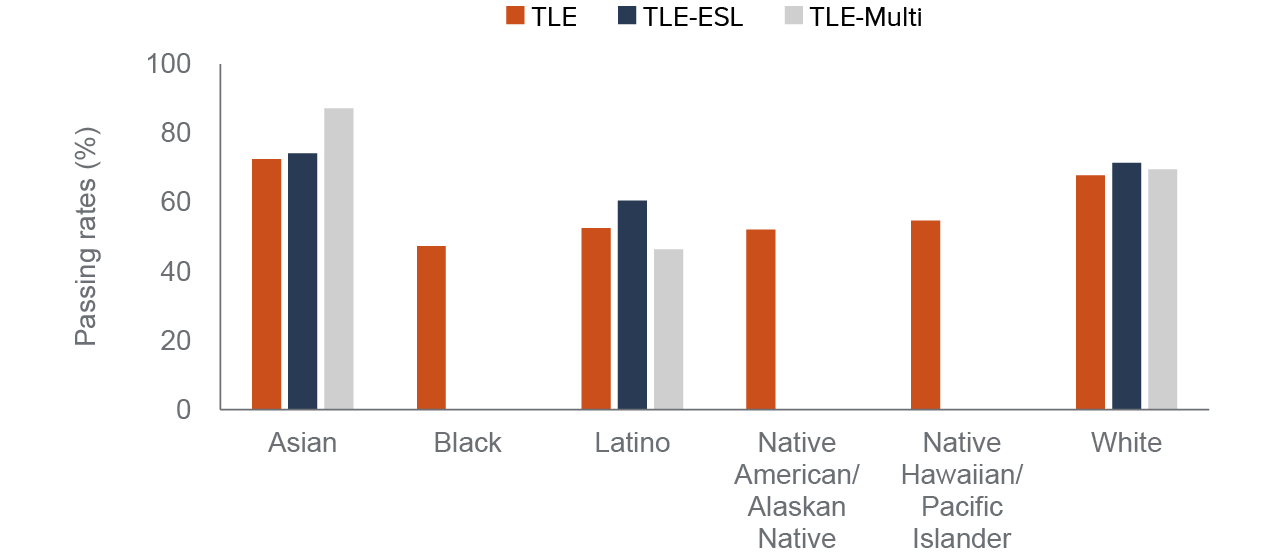

Degree-intending ESL students are more likely to be Asian, less likely to be Latino, and more likely to be white than the total population of ESL students (Figure 2). The racial/ethnic distribution of ESL degree-intending students has held steady over time (Technical Appendix Figure C5).

Higher proportions of degree-intending ESL students are Asian and lower proportions are Latino

SOURCE: Author calculations from Chancellor’s Office MIS data.

NOTE: Degree-intending ESL students are identified using ESL students’ self-reported goals.

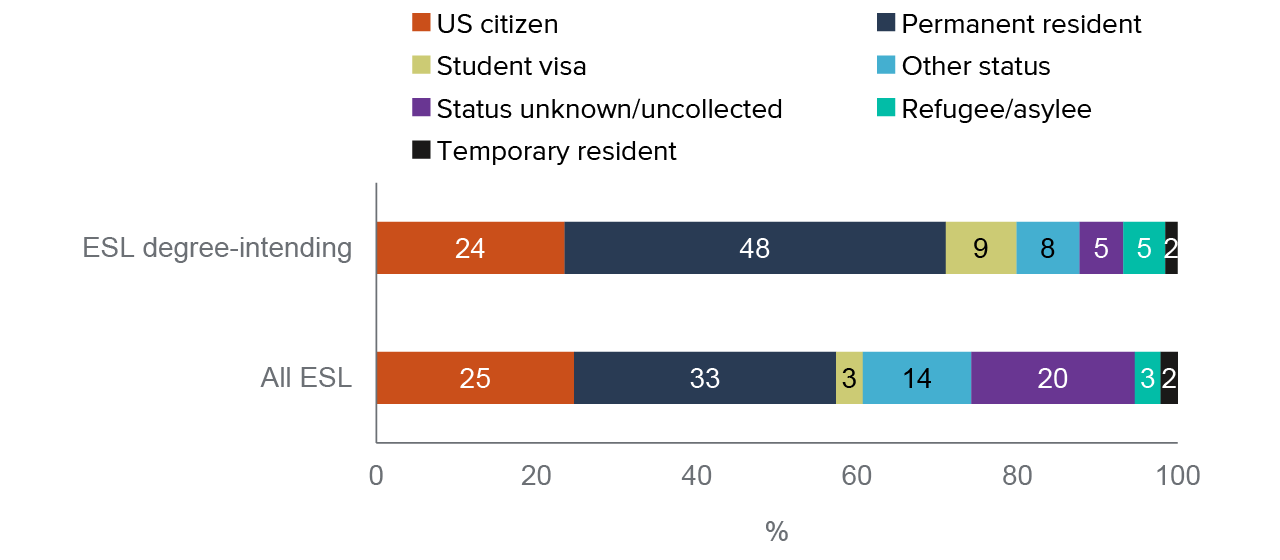

Degree-intending ESL students are much more likely to be legal permanent residents and student visa holders than ESL students generally, and they are less likely to be undocumented immigrants (Figure 3). The mix of immigration statuses was shifting before the pandemic and AB 705 implementation—as the share with student visas declined and the share of undocumented students rose (Technical Appendix Figure C6). Student visa holders are a relatively small share of degree-intending ESL students; they are slightly more likely to be Asian, less likely to be female, more likely to be of traditional college age (18–24), but no more likely to be foreign high school graduates than other visa status groups.

Degree-intending ESL students are more likely to be legal permanent residents

SOURCE: Author calculations from Chancellor’s Office MIS data.

NOTE: Degree-intending ESL students are identified using ESL students’ self-reported goals.

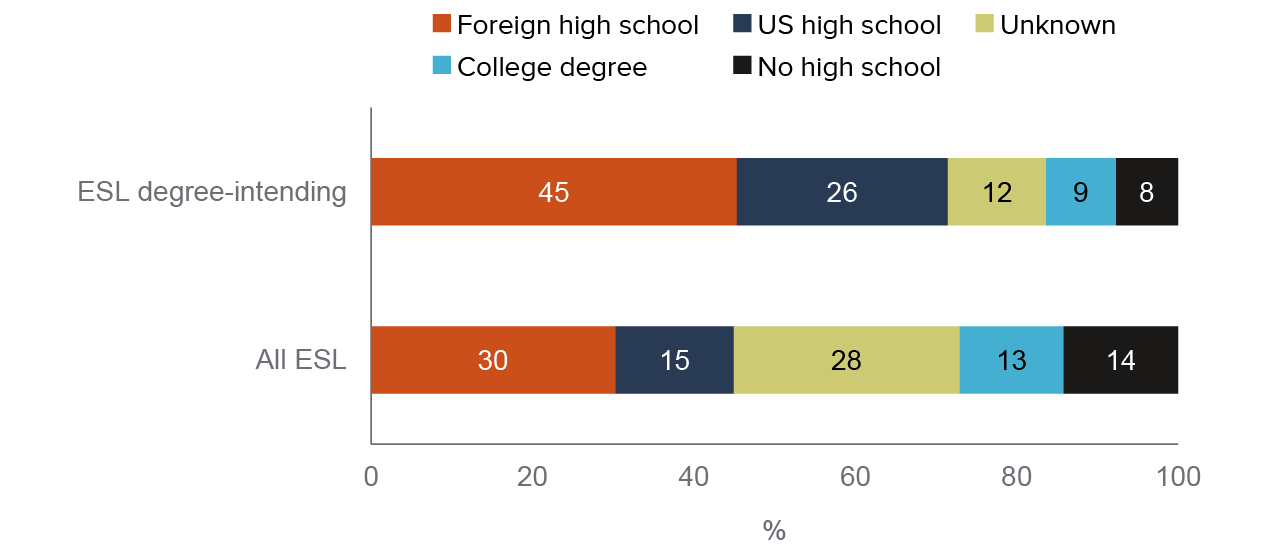

Degree-intending ESL students are substantially more likely to have graduated from high school (either in the US or in a foreign country) than the ESL population more generally (Figure 4). ESL students overall are nearly twice as likely to lack a high school diploma from any country and 4 percentage points more likely to have a college degree than ESL students seeking a degree. The number of degree-intending high school graduates enrolled in ESL courses has declined dramatically since 2015 (Technical Appendix Figure C7).

Most degree-intending ESL students have high school diplomas

SOURCE: Author calculations from Chancellor’s Office MIS data.

NOTE: Degree-intending ESL students are identified using ESL students’ self-reported goals.

How Have ESL Placement Policies Evolved under AB 705?

In this section, we explore ESL placement policies in fall 2021, the first term of systemwide AB 705 implementation. Comparisons of the placement policies across the CCC system before and under AB 705 are derived from a PPIC survey of placement policies during the 2014–15 academic year (Rodriguez et al. 2016) and an analysis of AB 705 adoption plans for the 2021–22 academic year. Where relevant, we also indicate how the ESL placement policy compares to the AB 705 English placement policy (Cuellar Mejia et al. 2020). Finally, we also report statistically significant differences in the length of the sequence and the characteristics of students at colleges reporting the use of the different placement methods.

Prior to AB 705, California’s community colleges used a variety of measures to assess English language skills, but all relied heavily on assessment tests (Bunch et al. 2011; Regional Educational Laboratories 2011; Rodriguez et al. 2016; Venezia, Bracco, and Nodine 2010). Although multiple measures were required by law prior to AB 705, we found that 100 percent of colleges relied on standardized assessment tests and only 12 percent reported using high school records to inform ESL placement (Rodriguez et al. 2016). It was common for colleges to use high school records (or other placement measures) only if a student challenged the results of the assessment test. As we report below, the implementation of AB 705 transformed ESL placement policies and practices across the system.

A student’s English learning journey varies widely and depends on placement results and the ESL course sequence offered by the college at which they are enrolled. At most colleges, for example, an EL with the highest results is typically placed into the highest level of ESL, one level below transfer-level English, but this same student might get direct access to transfer-level English (TLE) or an ESL equivalent (TLE-E) at other colleges. Also, students can be placed into an ESL sequence that varies in length from one level to more than eight (see Figure 8 and the next section for a more detailed discussion on the ESL sequence).

Direct access to college composition increased for ELs who are US high school graduates. California’s code of education regulations (also known as Title 5)—enacted in response to AB 705—now stipulate that ELs who are US high school graduates must be assessed using high school records and given direct access to transfer-level English or a transfer-level English ESL equivalent course. This requirement is supported by recent research suggesting that US high school graduate ELs are more likely to complete college composition if they enroll directly in that course instead of starting in an ESL course that is meant to build language competency (Hayward et al. 2022; Hayward 2020). We find that most colleges (83%) report using high school records and the default rules to place this group of students into these courses (see Technical Appendix Table B1 for more details about the rules). These default rules—which are research-based placement thresholds provided by the Chancellor’s Office—effectively direct all US high school graduates into TLE or TLE-ESL; a student’s high school GPA is used to determine the level of concurrent support needed (Hope and Stanskas 2018). The colleges that are not using the default placement rules are largely using guided or self-placement or an assessment test approved by the CCC Chancellor’s Office.

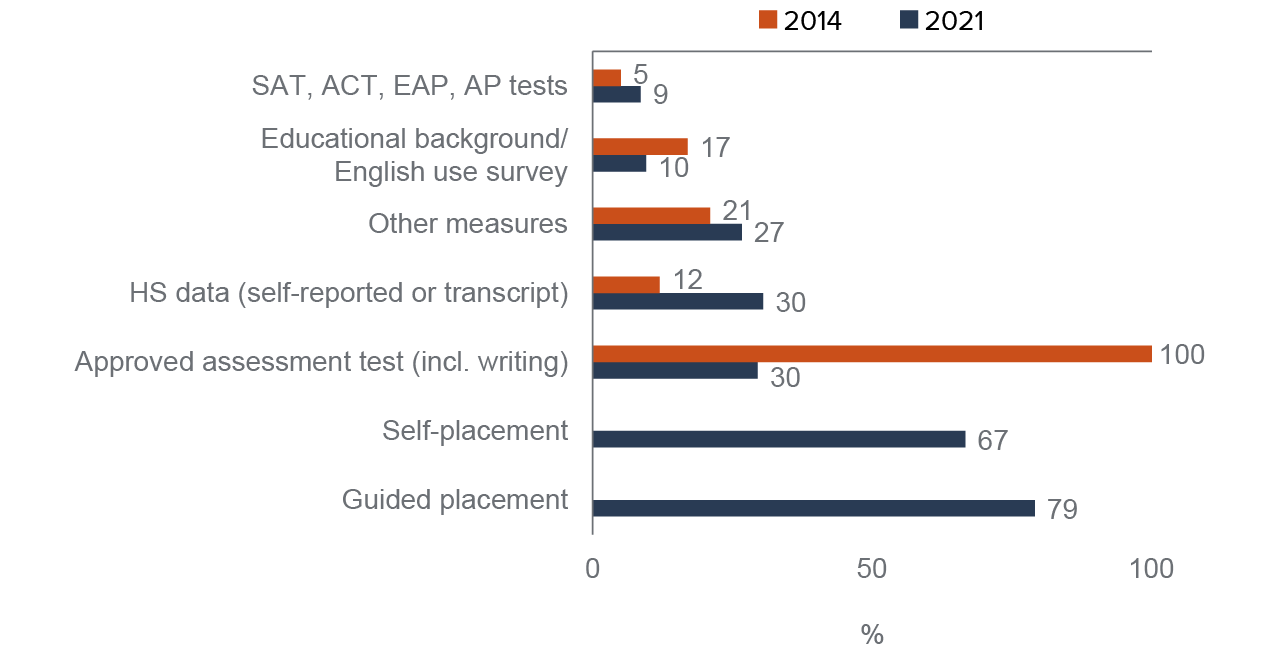

Placement policies for students who did not graduate from US high schools have varied considerably over time (Figure 5). In the past, the typical community college in California used two methods to determine placement within the ESL course sequence, in fall 2021 the number was three (Rodriguez et al. 2016; Technical Appendix Table B1). As seen in Figure 5, methods included those that have been traditionally used for placement, like assessment tests, as well as new methods, like guided placement.

ESL placement policies for non–US high school graduates have varied over time

SOURCE: Data on placement policies in 2021 is derived from authors’ calculations using CCC Chancellor’s Office AB 705 adoption plans submitted by 113 of 115 colleges in the CCC during the summer of 2021.

NOTES: Only the subset of colleges that submitted an AB 705 adoption plan and also offered an ESL sequence are included in the calculation (N=105 colleges). Data from 2014 derived from PPIC survey of assessment and placement policies that surveyed colleges on policies in place during the 2014–15 academic year (Rodriguez et al. 2016).

Under AB 705, many colleges have eliminated prerequisites to college composition and now grant direct access to this course to all students, including ELs who graduated from a US high school. Indeed, through our scan of ESL course pathways we found about one-third of colleges where no ESL course was listed as a prerequisite to college composition. Partly in response to this change, faculty indicated that colleges are seeking ways to support ELs who go directly into college composition. These supports are discussed below.

The use of assessment tests declined significantly. Colleges can use tests approved by the Chancellor’s Office to assess an EL’s reading comprehension, sentence skills, grammar skills, listening skills, and/or writing skills (Lowe 2022). These tests are typically multiple choice and can be completed either on paper or on a computer (see Technical Appendix B for an example). The writing assessments usually ask students to respond to a writing prompt, which is typically scored by two or more graders. Some of these tests are locally developed by individual campuses or districts, but most are standardized placement tests acquired from a third-party vendor (e.g., Accuplacer or CELSA). Both categories of assessment tests must be submitted for approval by the Chancellor’s Office.

Prior to AB 705, colleges relied on a variety of measures to determine a student’s placement into the ESL sequence, but all colleges relied on assessment tests. In contrast, in 2021, only 30 percent of colleges with an ESL sequence did so. This decline is likely attributable to both AB 705 and the pandemic. However, the use of assessment tests is still much more common in ESL than in English, where assessment tests are banned. Some faculty have argued that these assessments are needed to properly assess the English language skills of English Learners.

However, ESL faculty and department chairs identified the shift away from assessment tests as one way their policy is aligned with AB 705. Although the use of approved ESL placement tests was extended to July 1, 2021, some colleges were already headed in the direction of lower reliance prior to the implementation of AB 705 in ESL.

In examining the characteristics of colleges reporting the use of assessment tests, we noted interesting patterns: colleges that reported using assessment tests were more likely to have longer ESL sequences (5.3 courses vs. 4.4 courses), more likely to enroll Asian students (13% vs. 9%), and more likely to enroll permanent residents (7% vs. 5%), compared to colleges that did not use this method (Technical Appendix Table B3).

Assessment cut scores still vary across colleges. We find continued variation in the scores that determine ESL placement; as a result, an EL’s starting point in the ESL sequence depends largely on the college that student attends. For example, at colleges that reported their cut scores for placing students into the ESL course one level below college composition, we found that scores ranged from 100 to 114 for the Accuplacer reading skills test, and 63 to 70 for the CELSA. Some colleges also use the assessment to place students into TLE or TLE-ESL courses. This means that a student with a score of 115 on the Accuplacer reading skills test at a college with no TLE-ESL course will be referred to ESL one level below college composition, while this same student would be referred to TLE-ESL at a college that does offer that option. We find similar variation in the minimum cut scores students need to access TLE-ESL courses (Technical Appendix Table B2).

The use of high school records more than doubled. Not surprisingly, given the language of the law and the changes to Title 5 regulations, AB 705 helped increase the use of high school data for ELs graduating from US high school and helped bring some consistency to the way it informs the placement decisions for this subset of ELs. Namely, between 2014 and 2021, we find that the use of high school records for ESL placement more than doubled under AB 705, increasing from 12 to 30 percent (Figure 5). Prior to AB 705, data from high school records as a placement measure was often supplementary—used alongside the assessment test scores. Additionally, some colleges used high school data as an input in a placement algorithm, while others used this data only when students challenged their assessment test results (Rodriguez et al. 2016). This is an important improvement that aligns with the goals of AB 705 while recognizing that some ELs who graduate from US high schools may opt into the ESL course sequence. Still, it is worth noting that under AB 705, all CCCs reported using high school records for US high school graduates to determine placement into college composition (TLE or TLE-ESL), as mandated by the law.

Guided placement has become the most commonly used method. Nearly eight out of ten colleges reported using guided placement to inform ESL placement decisions (Figure 5). AB 705 allows colleges to use guided placement if high school records are unavailable. As part of a guided placement process, a college may provide students with course descriptions, sample course materials, and questionnaires to help them assess their reading and writing preparedness. One of the main goals of this process is to “encourage a student to reflect on his or her academic history and educational goals that may include the student evaluating their familiarity and comfort with topics in English or mathematics” (Perez 2019). Guided placement is designed to be a holistic approach that helps place students in courses that align with their educational goals and abilities. (See Technical Appendix C for examples of typical measures used.)

Self-placement is widely used. The Chancellor’s Office placement guidelines define self-placement as a “process in which a student chooses their placement after consideration of the self-assessment survey results and other relevant factors.” Instead of receiving a placement recommendation based on multiple measures such as test scores, educational goals, course information/materials, self-assessment of skills, and/or GPA, students determine their own placement after reviewing and reflecting on these various factors. Two-thirds of all colleges reported using self-placement in ESL (Figure 5).

We find that 66 percent of colleges that reported using self-placement also reported using guided self-placement (GSP). This is important, as recent research suggests that self-placement without guidance could have inequitable effects. Underrepresented students are more likely to have had negative academic experiences that have affected their confidence and perception of their academic abilities. In such cases, guided self-placement involves counselors or advisors encouraging students to believe in their capabilities (Brathwaite et al. 2022). (See Technical Appendix Table B1.)

While student engagement in the placement process was not a goal of AB 705, our interviewees characterized the process as student centered because it puts students in charge of assessing their goals, skills, and abilities. Faculty and department chairs lauded the GSP placement process as a way for colleges to provide “guidance, not placement.” Faculty at multiple colleges indicated under a GSP approach students are more empowered and are less likely to challenge their placement. However, faculty also indicated that it is important to encourage students to select the highest placement possible—to counteract a tendency to start at a lower level because that feels safer.

Use of counselors to inform student placement. A detailed analysis of colleges’ descriptions of placement policies found that 40 percent reported using counselors or ESL faculty to help inform the placement process, and 10 percent reported using ESL faculty or counselors specifically dedicated for ESL students (Technical Appendix Table B1). Some colleges use ESL welcome centers to support matriculation, registration, and retention among incoming and current ELs. Our faculty interviewees indicated that dedicated ESL placement support is critical, given that this population is especially likely to need support in navigating the college system. Dedicated counselors are keenly aware of the various challenges ELs face, such as learning a new educational system; residency issues; having to balance school, work, and family responsibilities; and having foreign degrees. Our interviews highlighted one ESL center in the Bay Area that engages in outreach at local high schools and connects students with financial aid opportunities, academic supports, and other student supports, like child care, food assistance programs, and other programs and benefits.

While counselors or advisors can enhance the placement process, it is also possible that their biases can have detrimental effects on student placement or decision making. Brathwaite and colleagues (2022) note that guided placement systems are best positioned to create equitable outcomes if counselors or advisors have been trained to identify biases and prevent them from affecting the guidance they provide students. This is of particular importance as we also found that colleges using GSP were more likely to enroll higher shares of Latino students (51% vs. 44%) and lower shares of Asian students (8% vs. 13%) compared to colleges not using this method (see Technical Appendix Table B3). No statistically significant differences emerged when examining gender or age.

There are benefits and challenges in moving from placement tests to guided self-placement. GSP is more accessible, can be easily conducted online, and can be made available in different languages. The placement test, on the other hand, requires a testing center and proctor, and has typically been offered only in English. Importantly, the assessment test must be approved by the CCC Chancellor’s Office, while the GSP relies on local validation practices. However, GSP can be labor intensive, as it requires faculty and counselors to develop and maintain the process—and to support students in making their placement decisions. The placement test, on the other hand, provides rapid placement recommendations based on one or more scores.

GSP can serve as the sole placement method because it naturally draws on multiple measures. For example, it is common for a GSP process to provide students with course sequence information as well as a questionnaire that asks students to report on their prior education. But because GSP data is often collected via locally developed online portals or through meetings with advisors/counselors, the data can be more difficult to integrate with administrative data. The computer-based nature of the assessment test has the advantage that it more seamlessly connects with the colleges’ student information systems. (Technical Appendix Table B4.)

How Are Colleges Structuring ESL Sequences under AB 705?

Community colleges have made dramatic changes to their ESL sequences. Sequences are shorter, more likely to be integrated across language skills (e.g., listening, speaking, reading, grammar, writing, vocabulary), and more likely to include an ESL version of transfer-level English. We drew from our scan of community college course catalogs for fall 2021, MIS data from the Chancellor’s Office, and our interviews with ESL department chairs and professors to understand how ESL courses were structured in the first semester of AB 705 implementation.

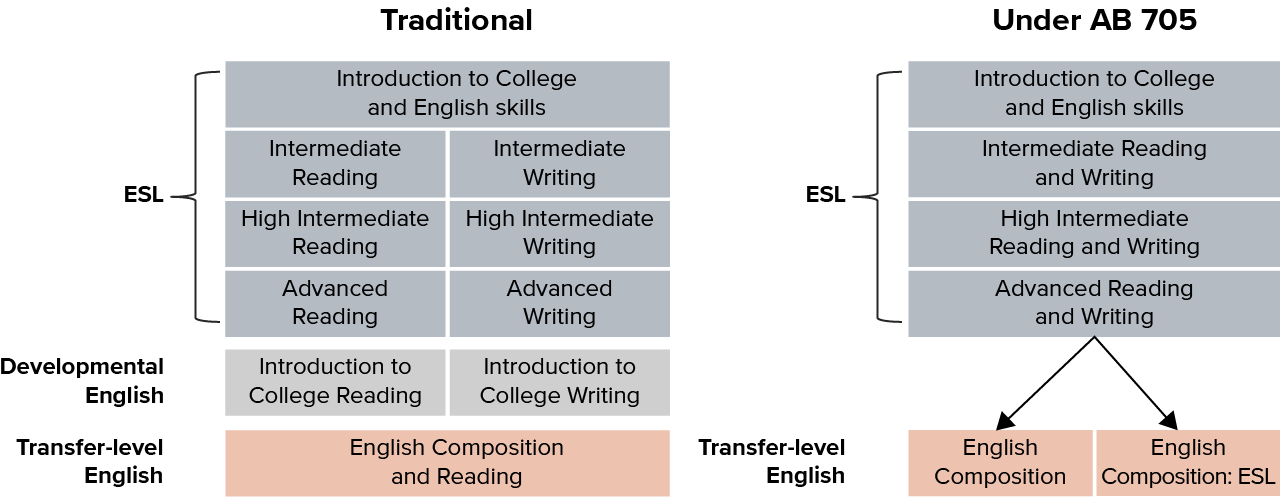

ESL pathways vary across college campuses, but we can draw a general picture of course sequences before and under AB 705. As of 2016–17, 29 colleges retained the traditional sequence depicted in the left side of Figure 6. In our scan of college course catalogs for fall 2021, we found that most colleges (90%) were offering integrated ESL courses (Figure 6). While our prior research demonstrated the effectiveness of integrated courses in increasing TLE completion (Rodriguez et al. 2019), at least one faculty member we interviewed reported an unintended consequence.

Under AB 705, essentially no colleges require ESL students to take developmental English prior to enrolling in TLE; 19 colleges (or 17%) offer an ESL version of TLE, and 3 colleges (Cabrillo, Diablo Valley, and Fullerton) offer TLE for multilingual students within the English department.

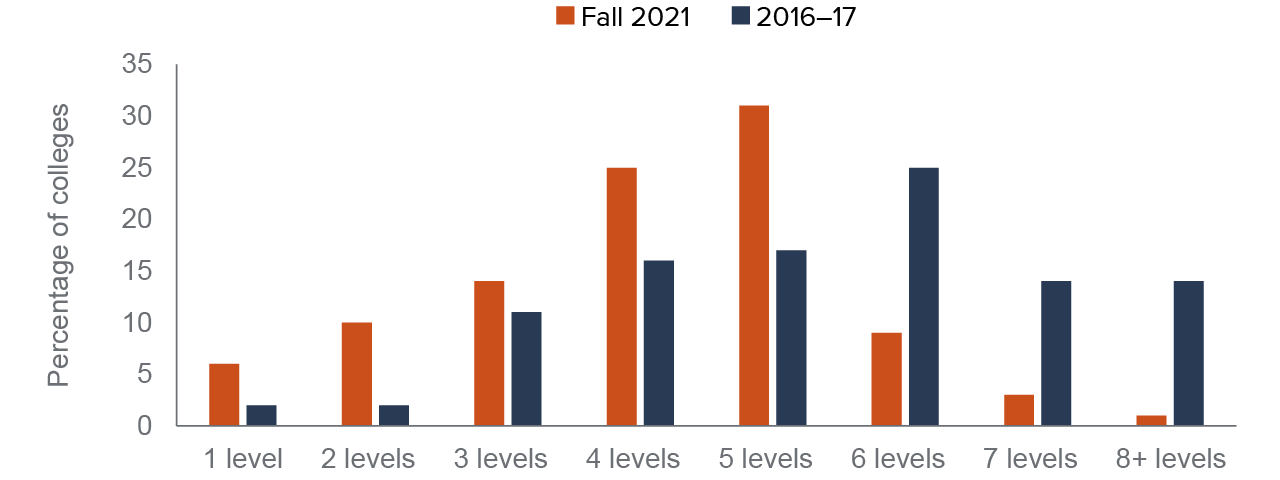

Skill integration and direct advancement to English Composition are hallmarks of course sequences under AB 705

In addition, colleges have dramatically shortened the ESL sequences that lead to TLE. Our prior research has shown that longer sequences mean students face greater risks of attrition, and if they are able to persist it means that students take longer to reach their goals (Rodriguez et al. 2019). Figure 7 illustrates that 87 percent of colleges now offer sequences with five or fewer levels. Prior to AB 705, 54 percent of colleges offered sequences with at least six levels, making it impossible for students starting at the first level to complete TLE within three years. Our interviews with ESL faculty and department chairs suggested that most ESL departments began revising their ESL curricula in anticipation of the AB 705 deadline. Of course, where students begin is more important than how long the sequences are. We examine sequence placement in the next section.

As noted earlier, enrollment was down systemwide during the pandemic, particularly among ESL students. At some campuses, ESL faculty reported that this led to course cancellations and meant that not all ESL sequence courses were offered or that some courses were combined.

Colleges have shortened their ESL sequences

SOURCE: Course catalog scans from 2021–22 (fall only) and 2016–17 school years.

NOTE: The length of the sequence is based on a backward mapping of the ESL course sequences that lead to transfer-level English or the ESL equivalent course.

A few types of courses meant to increase ESL students’ success in completing transfer-level English are worth highlighting. First, we look at ESL courses that are transferrable to the UC, CSU, or both systems as elective units. Among the ESL credit courses leading to TLE, the transferability rate is about 16 percent (12% to either UC or CSU and 4% to CSU only) and the share of courses that has both UC and CSU approval has increased slightly since we last examined transferability for ESL (from 10% to 12%; Rodriguez et al. 2019). And increasingly, advanced ESL courses are approved for direct fulfillment of general education requirements—not just as elective credits.

Next, there are corequisite support classes tailored for students needing extra support because they are either current or former English Learners. Students take these sections simultaneously with English composition in either the English or ESL departments. Not many colleges offer them—we only identified four. Some corequisite courses are for any student who might need additional support in TLE, not just ESL students. Some colleges offer corequisite courses that are exclusively for ESL students. There is variation across the colleges offering these sections. Some corequisite sections are linked to specific sections of the TLE courses. Some corequisites are taught by the same instructors that teach the English composition class, and some are taught by different instructors (who are ESL instructors). While we are very interested in understanding the role of corequisites in ESL student outcomes, this variety poses a challenge.

Finally, some colleges have developed TLE courses specifically for multilingual English Learners. At least five courses at three colleges are offered within the English department, while at 19 colleges these courses are housed in the ESL department. Courses in ESL departments are typically taught by faculty with the minimum qualifications to teach ESL, while those taught in the English departments are taught by faculty with minimum qualifications in English but have backgrounds or training in supporting English Learners. Both meet the English composition requirements of a standard TLE course and most are transferrable to the UC and CSU systems. These college composition courses provide additional support to multilingual learners and are intended just for those students. They represent a notable improvement since 2019, when only five colleges offered TLE-ESL equivalent courses, and not all of them were transferable to all UC and CSU campuses. This meant that many students had to take the standard TLE in the English department to meet the transfer requirements (Rodriguez et al. 2019).

In our interviews with ESL faculty and department chairs, we learned that TLE courses taught within ESL departments usually have more scaffolding—especially for writing assignments—and embedded tutors. Colleges that had successfully developed, secured Intersegmental General Education Transfer Curriculum (IGETC) 1A and CSU A2 approval credit, and implemented TLE-ESL highlighted the strong relationships the ESL and English departments shared—alignment and/or collaboration between the two departments was cited as critical to their success. More than once, ESL faculty reported that some English faculty were happy to have separate courses of TLE for ESL students because they felt less equipped to meet the academic needs of ELs in a standard TLE course. Not all colleges have succeeded in implementing TLE-ESL classes. We heard from one ESL faculty member that the English department was resistant—in part because students who completed the ESL sequence were highly successful in English composition.

Enrollment and Outcomes for Degree-Intending ESL Students

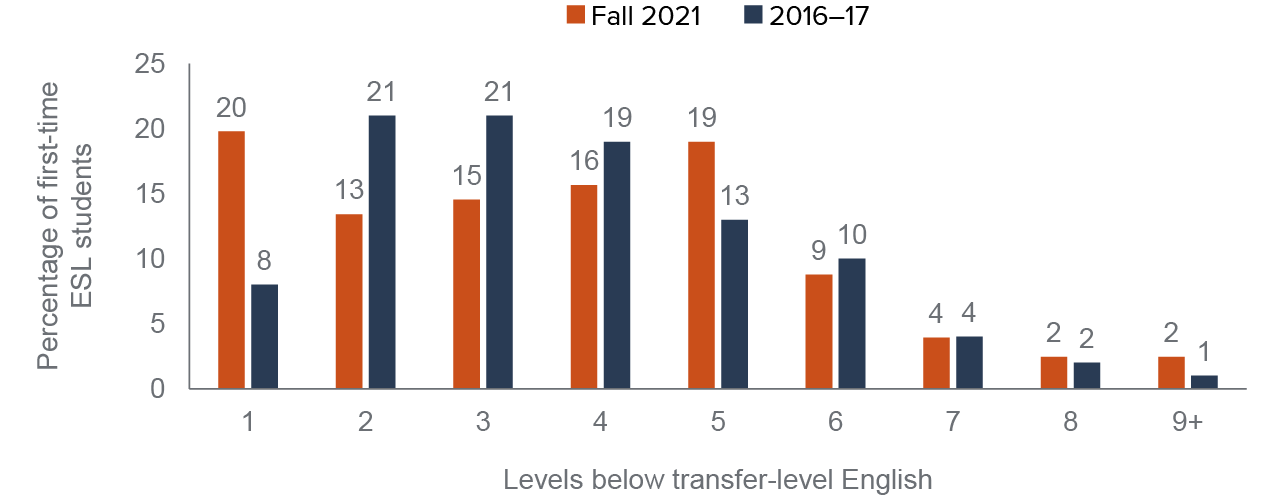

In this section, we look briefly at enrollment in ESL sequences and examine successful completion of Transfer-Level English (TLE) for first-time students. Overall, we find that more students are starting ESL sequences at higher levels than in 2016, and that students enrolling in TLE courses designed for English Learners have very high success rates. The same is true for students who took their first community college course in fall 2021 (first-time students) and students who had been enrolled in the college prior to this term (continuing students). However, comparing success rates in fall 2021 to prior success rates in these courses is challenging because the mix of students taking them has changed along with the course structures and the sequences. This is partly because implementation has occurred entirely during the COVID-19 pandemic. As a result, the changes to enrollment and outcomes presented in this section cannot be attributed exclusively to AB 705.

As we have seen, ESL sequences offered by colleges were dramatically shorter in the first semester of full AB 705 implementation than they were in 2016–17. We find that students in ESL sequences are much more likely to start just one level below TLE—close to 20 percent in fall 2021 compared to 8 percent in 2016–17 (Figure 8). If they are to complete TLE within six semesters, new students need to start no more than five levels below TLE. We find that the share of students starting between one and five levels below TLE has held steady (82% in fall 2021; 83% in 2016–17). But because many students who might have been placed in ESL sequences in the past are now able to enroll directly in TLE, the distance to the English gateway courses is shorter.

Under AB 705, first-time ESL students are more likely to start one level below TLE

SOURCE: Authors’ calculations using COMIS data.

NOTES: Degree-intending students are coded according to their first sequence ESL course, for students who first enrolled between the 2009–10 and 2016–17 academic years (N=120,365) and for 2021–22 (N= 5,146). Colleges are coded according to the longest sequence offered in the academic year. If ESL coursework leads to developmental English, the developmental English course(s) count in the sequence. ESL sequences do not include students enrolled in TLE courses.

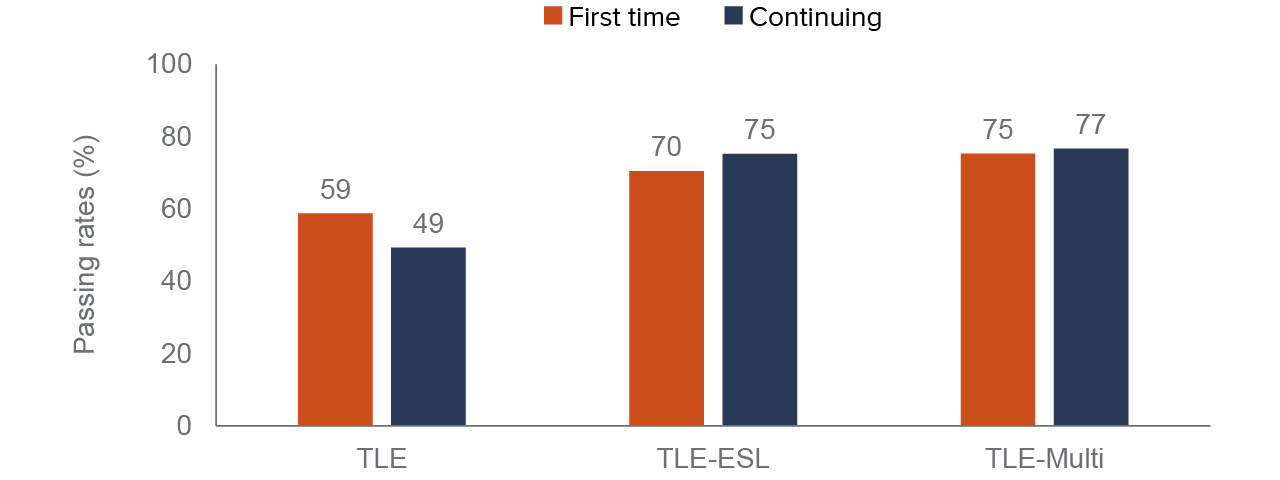

Now we examine outcomes for TLE and TLE-ESL students in fall 2021 (159,928 and 754 students, respectively), the first semester when community colleges were required to implement the new placement procedures and course structures mandated under AB 705. We examine pass rates in TLE separately for first-time community college students (those taking their first community college class) in fall 2021, the first term under which placement and course structures are mandated by AB 705 and continuing students (those who took community college courses prior to fall 2021).

First-time students (103,032 out of 160,682) passed TLE at a rate of 59 percent (Figure 9); this rate is similar to what Cuellar Mejia et al. (2022) found in their analysis of fall 2020 students who were not specifically identified as ELs. Fall 2021 students were the first cohort to go through the ESL placement process outlined in AB 705, whereby ELs who are US high school graduates are placed directly into TLE, TLE-Multilingual, or TLE-ESL, unless they choose a different placement. Unfortunately, because our data does not include information about students’ academic or linguistic background, we are unable to identify enrollment and outcomes for ELs in the mainstream TLE course. Due to these data constraints, we cannot tell how well ELs are doing in mainstream TLE courses.

Passing rates are higher in courses designed for ESL or multilingual students

SOURCE: Authors’ calculations using COMIS data.

NOTES: TLE is the standard transfer-level English class taught by the English department, TLE-ESL is taught by ESL faculty at the ESL Department, and TLE-Multilingual is a TLE course taught in the English department, usually by ESL faculty, with additional support for multilingual learners. Passing rates from fall 2021 term. N is 159,928 for TLE, 754 for TLE-ESL and 227 for TLE-Multi.

Most notably, fall 2021 passing rates are much higher among students taking TLE-ESL courses. First-time and continuing students in both TLE-ESL and TLE-Multilingual courses have passing rates above 70 percent. (Continuing students do slightly better, possibly because they took prior ESL courses.) These high passage rates suggest that efforts to develop and implement these courses are promising. However, future research should monitor their effectiveness as they become more prevalent. It will also be important to examine EL outcomes in higher-level English courses, particularly those that fulfill the Critical Thinking IGETC 1B/CSU A3 requirements. Future research should also look closely at curriculum, instruction, academic supports, and peer effects in these courses.

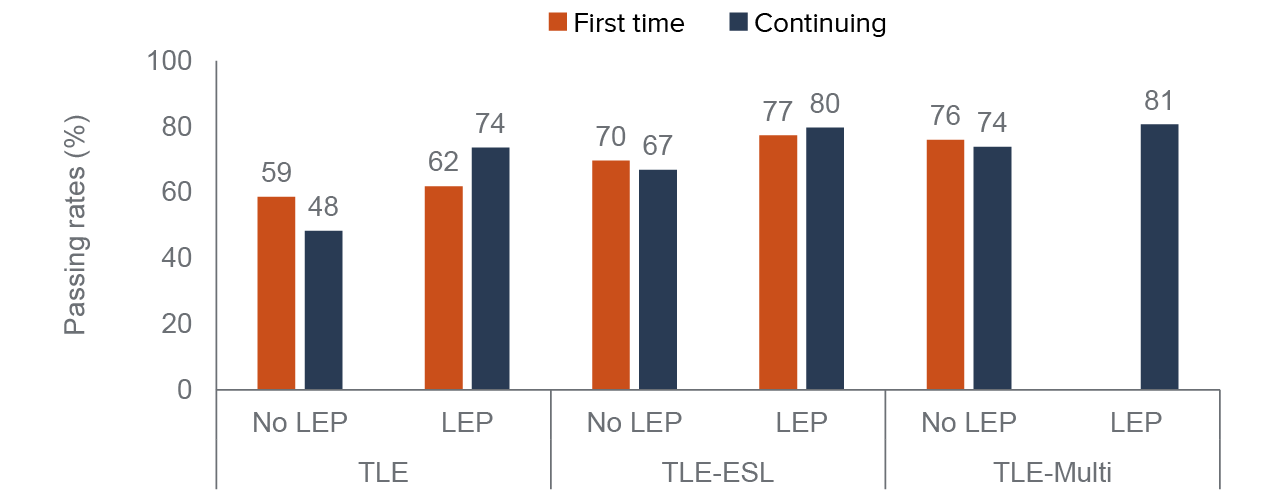

Due to data limitations, we are unable to identify the group of ELs who bypass ESL courses and enroll directly in TLE. However, by using the Limited English Proficient (LEP) identifier included in the MIS student-level data we can determine whether a first-time EL student taking a TLE course also enrolled in a corequisite or another ESL course. The LEP identifier is also helpful in examining outcomes of continuing EL students who started at a college before fall 2021 and most likely took ESL classes that are part of the sequence to prepare for TLE. We can use the LEP identifier included in the student-level data to examine outcomes for this group of English Learners.

We find that passage rates among first-time TLE students who took ESL courses (using the LEP flag) are slightly higher (62%) than first-time students who did not (59%) (Figure 10). We also find that passage rates for continuing EL students are much higher (74%) than rates for all first-time students and for continuing students who are not ELs (48%). Continuing EL students likely took courses in the ESL sequence prior to enrolling in TLE in fall 2021; we find that the number of ESL courses completed by this group of students was on average 4.6. These students’ positive outcomes provide suggestive evidence of reports we heard from some ESL faculty that students who have succeeded in the ESL sequence are prepared for TLE and might have successfully completed TLE earlier. Indeed, these are the students AB 705 is designed to benefit.

English Learners identified as LEP students have higher pass rates than non-LEP students in all TLE class types

SOURCE: Authors’ calculations using COMIS data.

NOTES: Passing rates from fall 2021. Passing rates from fall 2021 term. LEP students are identified by having taken an ESL course before or at the same time than the TLE course. Results are omitted when cell size is less than 10. N is 159,928 for TLE, 754 for TLE-ESL, and 227 for TLE-Multilingual.

The students who are most likely to pass TLE are continuing ELs in a TLE-Multilingual learner course (81%), followed closely by continuing EL students enrolled in a TLE-ESL course (80%). ELs with prior ESL course-taking experience also pass the standard TLE class at very high rates (74%). No matter the class type, ELs identified as LEP students have higher pass rates than all non-LEP students (which includes students who graduated from US high schools). This suggests that even in TLE-ESL or TLE-Multilingual classes, concurrent ESL or prior courses could be helpful. However, our prior research suggests that attrition in long ESL sequences is a major problem (Rodriguez et al. 2019). Notably, the passing rates are similar enough for first-time (77%) and continuing ESL students (80%) taking TLE-ESL courses to indicate that the benefits of prior course taking may not be worth the additional time and expense for ELs who are US high school graduates, and that support courses would be enough to foster students’ success.

How Do Outcomes Vary across Demographic Groups?

We next explore TLE passing rates by gender, age, educational attainment, race/ethnicity, and immigration status. Overall, the findings we observed in Figures 10 and 11 hold for our analysis by gender, educational attainment, and race/ethnicity—passing rates are higher in TLE-ESL and TLE-Multilingual courses. The story for citizenship status is less clear.

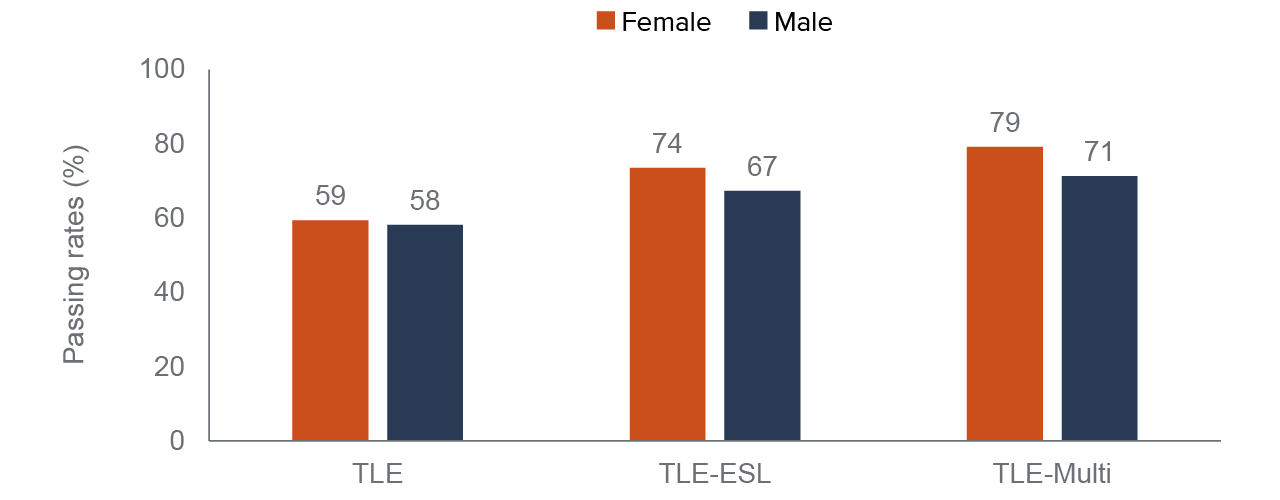

Female students are more likely to pass TLE courses than male students (Figure 11). Both male and female students in TLE-Multilingual courses are more likely to pass than female and male students taking TLE-ESL and TLE.

Female first-time students are slightly more likely to pass TLE

SOURCE: Authors’ calculations using COMIS data.

NOTES: Passing rates from fall 2021. First time community college students. N is 102,812 for TLE, 220 for TLE-ESL, and 154 for TLE-Multilingual.

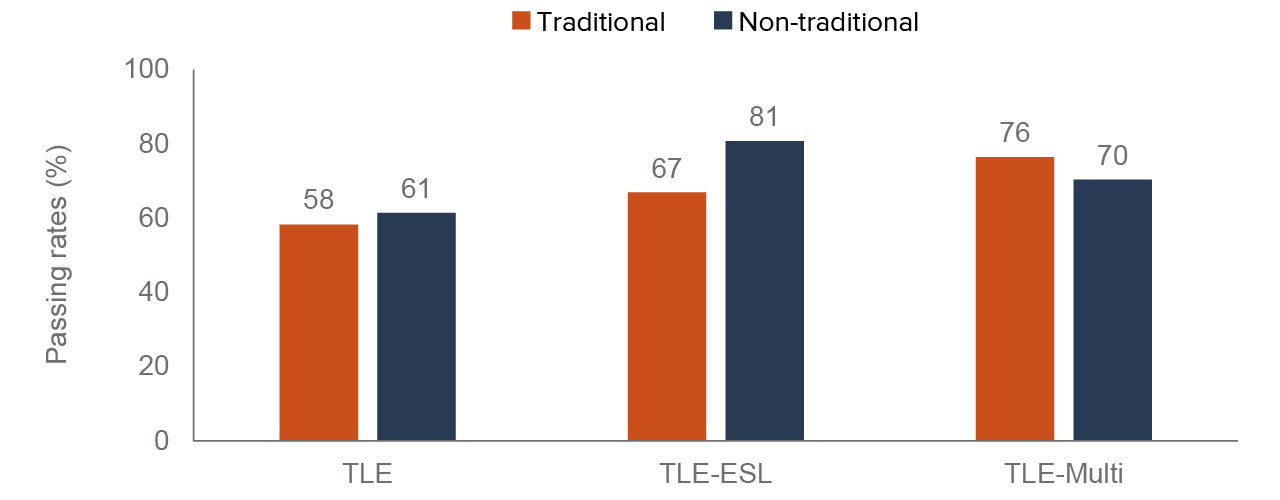

Passing rates for non-traditional-aged students (older than 24), were higher than those for traditional-aged students (between 18 and 24 years old) in TLE and TLE-ESL (Figure 12). For TLE-Multilingual, traditional-aged students had better pass rate. Almost 75 percent of the first-time students enrolled in TLE-ESL were between 18 and 24 years old; for TLE and TLE-Multilingual the share was greater than 80 percent.

Non-traditional-aged students are more likely to pass TLE and TLE-ESL courses

SOURCE: Authors’ calculations using COMIS data.

NOTES: Passing rates from fall 2021. First-time community college students. N is 102,761 for TLE, 220 for TLE-ESL, and 154 for TLE-Multilingual.

Across racial/ethnic groups, first-time Asian students were the most likely to pass standard TLE courses (73%), followed by white students (68%), Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander (55%), Latino (53%), Native American/Alaskan Native (52%), and Black students (47%) (Figure 13). Latino students taking TLE-ESL have higher passing rates than those placed in standard TLE (61% vs. 53%) as well. However, pass rates for Latino students are lower in TLE-Multilingual than in TLE-ESL or TLE courses. This could be because there were only 24 Latino students taking these classes, and they may not have been representative of potential TLE-Multilingual students. Also, since these courses are offered at only three community college campuses, these results should be interpreted with caution.

TLE-ESL passing rates are higher than TLE passing rates for all racial/ethnic student groups

SOURCE: Authors’ calculations using COMIS data.

NOTES: Passing rates from fall 2021. First-time community college students. N is 102,812 for TLE, 220 for TLE-ESL, and 154 for TLE-Multilingual.

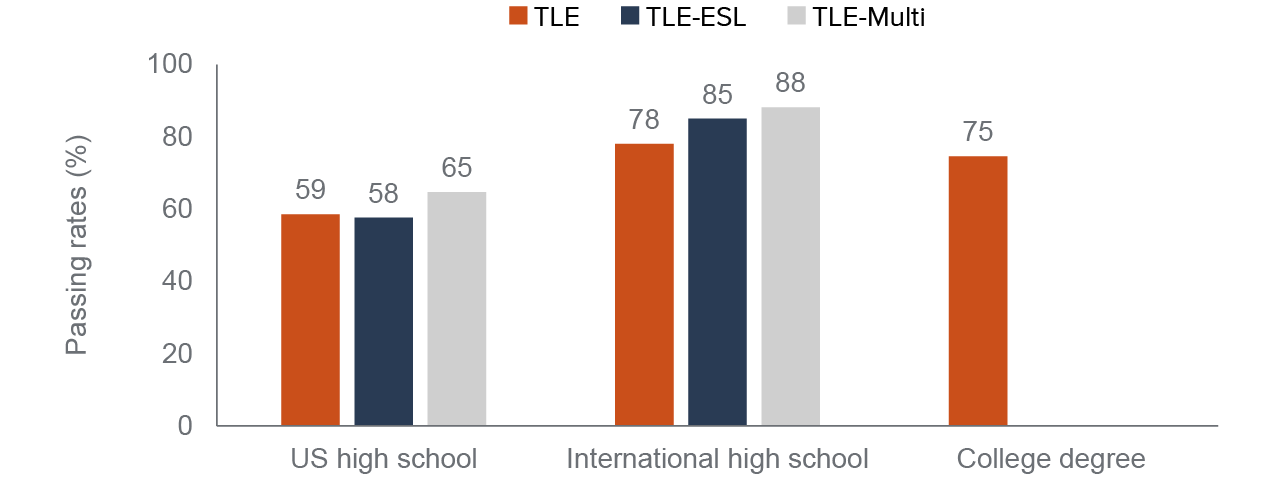

Now that US high school graduates are placed by default into standard TLE, it is important to investigate passing rates across TLE course options. We find that passing rates are very similar for US high school graduates in TLE and TLE-ESL, and 7 to 8 percentage points higher in TLE-Multilingual (Figure 14). International high school graduates in TLE-Multilingual classes also outperform those in TLE-ESL, but the gap is smaller (3 percentage points).

International high school graduates have the highest passing rates, especially in TLE for English Learners

SOURCE: Authors’ calculations using COMIS data.

NOTES: Passing rates from fall 2021. First-time community college students. N is 102,812 for TLE, 220 for TLE-ESL, and 154 for TLE-Multilingual.

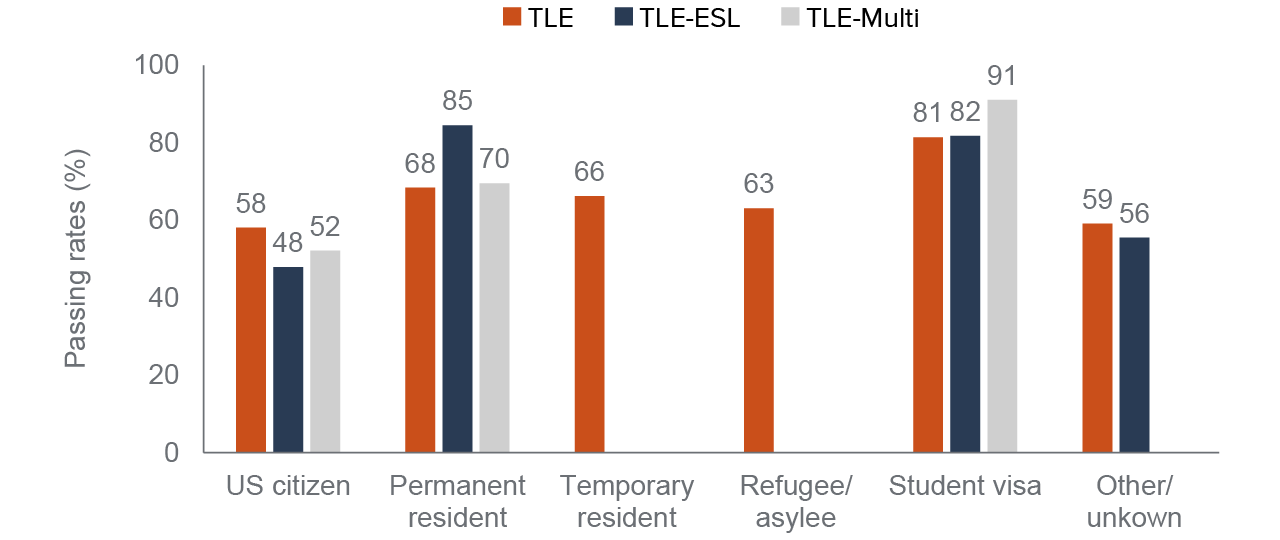

As we noted earlier, passing rates are generally higher in the TLE-ESL and TLE-Multilingual courses than in standard TLE. However, that is not true for all immigrant status groups. US citizens are more likely to pass their TLE course if it is the standard TLE (Figure 15). The same is true for the group that is likely to be undocumented (other/unknown status), although we cannot examine passing rates for TLE-Multilingual because there are insufficient numbers of undocumented students enrolled in those classes. Permanent residents and student visa holders are the most likely to pass their TLE-ESL courses. This does not appear to be related to prior educational attainment—refugees are the most likely to have at least a high school diploma (94%) and student visa holders are among the least likely (61%). A relatively high proportion of permanent residents (84%) have at least a high school diploma.

Student visa holders have especially high passing rates for any type of TLE

SOURCE: Authors’ calculations using COMIS data.

NOTES: Passing rates from fall 2021. First-time community college students. N is 102,812 for TLE, 220 for TLE-ESL, and 154 for TLE-Multilingual.

In this first semester of AB 705 implementation, during a period of adaptation to instructional and enrollment changes, we find some evidence that students placed directly in TLE, TLE-ESL, and TLE-Multilingual classes did relatively well. However, future research should examine additional first-time cohorts of students as well as examine later outcomes, including completion of more advanced coursework, associate degrees awarded, and transfers to the CSU and UC systems.

Conclusion and Recommendations

We find that California community colleges have made important progress in implementing AB 705’s ESL placement reforms by moving away from a heavy reliance on standardized assessment tests and toward the adoption of multiple measures and guided placement policies. These changes are expanding opportunities for students to meaningfully engage with the placement process. AB 705 prompted changes to Title 5, California’s code of education regulations: US high school graduates must now be placed directly into college composition. Also, colleges have restructured their ESL sequences to align with AB 705: they have made great strides in shortening the length of sequences, integrating skills, and increasing opportunities for ESL course transferability. Our previous research suggests all of these features are positively associated with improved short- and longer-term outcomes for English Learners (Rodriguez et al. 2019).

Still, our student data and interviews indicate that the work is far from over. Given the three-year timeframe AB 705 provides ESL for the completion of transfer-level English or the ESL equivalent, it is too early to assess the effects of the reform on this key outcome. AB 705 implementation in ESL has occurred during a historic pandemic, which will continue to pose challenges and create opportunities moving forward. Drawing on our examination of the first year of AB 705 ESL implementation, we offer a set of recommendations intended to improve student success at California’s community colleges.

Expand access to college composition for all English Learners. Research examining early implementation of AB 705 has shown that direct access to the gateway course is the single most impactful way colleges can increase the number of students who successfully complete gateway courses (Cuellar Mejia et al. 2020, 2021, 2022). Recent research and our analysis of the first term of implementation for ESL suggest that a similar story is emerging: providing direct access to college composition to ELs produces higher rates of successful completion than requiring ELs to begin in an ESL course below college composition (Hayward et al. 2022). AB 705 has helped open the door to college composition to ELs who graduate from a US high school. A growing number of colleges across the system have stepped up to support ELs at this level by offering a TLE-ESL equivalent course, a TLE designed for multilingual speakers, or corequisite support tailored to the needs of ELs. Our analysis of the first semester of AB 705 implementation suggests these students have high passing rates (above 70%).

Given these outcomes, all colleges should be encouraged to innovate in designing college composition courses that support the needs of all English Learners, including those who do not graduate from a US high school. Ultimately, the type of dedicated EL support in college composition will depend partly on faculty expertise, the relationship between the English and ESL departments, and curriculum committees and IGETC/CSU articulation. As these courses become more widespread, it will also be imperative that future research monitor whether the courses are effective and whether access and outcomes are equitable.

Monitor the validity and effectiveness of placement rules. The importance of expanding access to college composition for ELs and providing them with support is heightened by our analysis of ESL assessment cut scores and our finding that colleges using assessment tests have longer ESL course sequences on average. In fall 2021, colleges using a test had about one additional ESL course in their sequences and colleges using the same instrument are using different cut scores to determine access to the one-level-below-ESL courses and the TLE or TLE-ESL courses, if those are an option at the campus. It is likely that there is also variation in other placement methods—for example, if ESL guided placement requires placement into ESL, even when ELs may be better served by direct access to TLE or TLE-ESL. As such, it will be critical for the Chancellor’s Office and individual colleges to assess the validity and effectiveness of the rules used across placement methods. Per our recommendation above, all colleges could work toward systematically providing access to TLE courses designed for English Learners. Otherwise, inequitable outcomes will persist, as a student’s chances of completing TLE will continue to depend on where that student enrolls in college.

Make deliberate connections between ESL reforms and other systemwide initiatives. The rising number of ESL courses that are transferrable to both UC and CSU offers opportunities to connect ESL reform with larger systemwide initiatives. The TLE-ESL equivalent courses are now actively contributing to a key metric used in the Vision for Success and the funding formula. Offering transferrable ESL courses through College and Career Access Pathways (CCAP) dual enrollment partnerships could boost enrollment while also boosting college-going among EL students in high school. Such an approach is being adopted at Cuyamaca College. Additionally, colleges could adopt the approach taken by Cypress College, which created ESL milestone certificates to recognize student achievements in learning a language and completing prerequisite courses in a program of study (Rodriguez et al. 2019; RP Group 2021). This approach connects ESL with AB 705, Guided Pathways, and the Vision for Success. A next phase in this innovative work could extend milestone certificates to high school students through dual enrollment.

Provide guidance and information to ongoing implementation efforts. After noting that they benefitted from pre-implementation guidance from the Chancellor’s Office, many faculty and department chairs expressed a desire for more formative guidance and information from the Chancellor’s Office about how implementation is going. For example, we heard that a lot of time and effort went into submitting AB 705 adoption plans last summer, but that colleges had not yet received much direct feedback about their plans. A number of faculty and department chairs also expressed concern about the uncertainty around AB 1705 and how it will affect ESL—several were concerned that the new proposed legislation might mean they could not offer any ESL courses that are not transferrable. It will be important to clarify how AB 1705 will affect ESL.

It will also be imperative for researchers to help inform and improve ongoing AB 705 implementation efforts in ESL. In the implementation of AB 705 in math and English, the research community came together to provide timely data and evidence that helped shape implementation efforts and policy refinements. Future work could examine the impact of Assembly Bill 2121 (Caballero)—which exempts newcomer students and other special populations from local high school graduation requirements—on college readiness and AB 705.

Establish a longitudinal data system. One notable limitation of this study is that we are unable to observe all EL students who enroll in the CCC—we are only able to identify ELs based on ESL course taking (or per the LEP flag). Linked K–12 and postsecondary data would allow us to identify all US-educated ELs. There could be important equity gains if high schools and CCCs were able to share data and automate what is currently a complex application process. Longitudinal data is especially critical for accurately identifying and meeting the needs of EL students. Given that the goal of so many ELs is to improve language skills and employment prospects, connecting the data to labor market outcomes is also essential. The governor and the legislature are supporting efforts to establish a data system that connects K–12, higher education, workforce, and social services data; this system would include information on high school English Learner status (Jackson 2021).

It is important to reiterate that ESL programs across the system have worked tirelessly to implement AB 705 while simultaneously responding to the challenges posed by a historic pandemic. The encouraging findings should provide reassurance that the work colleges have been doing is bearing fruit in spite of all they have faced. Supporting English Learners in acquiring a postsecondary education is critical in light of California’s demographic trends, future workforce needs, and the demand for college graduates.