Table of Contents

- Key Takeaways

- Introduction

- The Pandemic and Community College Enrollment among Transfer-Intending Students

- The Pandemic and the Composition of Transfer-Intending Cohorts

- The Pandemic and Persistence across Terms among Transfer-Intending Students

- The Pandemic and the Academic Progress of Transfer-Intending Students

- Conclusion and Recommendations

- Glossary of Terms

- Notes and References

- Authors and Acknowledgments

- PPIC Board of Directors

- Copyright

Key Takeaways

COVID-19 hit in the middle of the spring 2020 term, forcing California’s community college system to shift immediately to an online learning environment, and widening inequities in access and well-being between students. The effects of such disruptions on student outcomes are just beginning to emerge. In this report, we analyze short- and medium-term outcomes through the fall 2021 term, focusing on students who intend to transfer to a four-year university, a group that accounts for 57 percent of total enrollment.

- The pandemic magnified challenges with attrition and retention: enrollment among transfer-intending students declined by 20 percent from fall 2019 to fall 2021. Asian, Black, and Latino students faced disproportionately large drops in student counts, especially among first-time students. →

- While continuing students who enrolled during the pandemic had better academic histories than students enrolled in previous terms, and this group was relatively successful, continuing students over time had been entering the fall with stronger academic histories before the pandemic. →

- Persistence and successful completion of at least one course in subsequent terms fell modestly. Latino and first-time students faced the largest declines, and Black and Latino students were disproportionately represented among transfer-intending students who did not persist. →

- Students who remained enrolled during the pandemic maintained steady unit accumulation, and a higher share reached critical milestones along the transfer pathway—a likely effect of pre-pandemic reforms aimed at widening access to and success in transfer-level coursework. However, gaps in student success that predated the pandemic remained. →

- For an effective recovery, the state must prioritize collaborative efforts that improve enrollment, prevent future declines in transfer attainment, narrow equity gaps, strengthen student supports and course offerings to meet student needs, and expand opportunities for institutional and external research. →

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated the digital divide in education and disrupted learning—hitting vulnerable communities the hardest—as institutions of all levels scrambled to provide quality remote instruction. The state’s community colleges were not left unscathed. Enrollment plummeted while the need for expanded supports heightened for students and instructors alike (Bulman and Fairlie 2022; Linden et al. 2022; California Student Aid Commission 2020).

California’s community college system is the largest in the country, comprising 115 credit-bearing colleges and serving almost 2 million students each year, a majority from low-income and historically underrepresented groups. Because of this, the system is central in the state’s efforts to improve economic mobility, especially through transfer, as the value of a four-year degree, and the state’s need for more college graduates, remains high.

A considerable share of graduates from the University of California (UC) and California State University (CSU) systems are students who transferred from a state community college. Accordingly, the pandemic’s effects on community colleges—especially among Black, Latino, first-generation, and low-income students—have large implications for economic recovery and growth in California, informing future efforts to improve outreach, supports, modes of instruction, and policy.

Before the pandemic hit in the middle of the spring 2020 term, several reform efforts were underway across the community college system. Implemented in fall 2019, Assembly Bill (AB) 705 has significantly reshaped how California community colleges place and remediate students, widening access to and success in gateway transfer-level courses in English and math (Cuellar Mejia, Rodriguez, and Johnson 2020; Cuellar Mejia et al. 2021; Cuellar Mejia et al. 2022). Additional reforms, such as Guided Pathways and Associate Degree for Transfer (ADT), are meant to ensure more students persist beyond these introductory courses to reach their educational goals. Such efforts have proven crucial as the system strives to meet its own five-year goals set out in its Vision for Success in 2017, including significantly increasing transfers to UC and CSU and reducing equity gaps across a variety of student success metrics.

Then the pandemic hit, forcing community colleges to move instruction and student support services—such as academic advising, mental health counseling, financial aid, and tutoring—to online settings (Hart et al. 2021). Colleges provided their students with emergency aid and resources that included technology, food, and housing services, and cash assistance, while widening access to training in online course development for faculty. The California Community Colleges (CCC) Chancellor’s Office provided widespread administrative relief and guidance, expanded online resources and technical assistance for faculty and staff, and enacted policy changes— including suspending regulations on excused withdrawals—to ensure that students were not penalized academically or financially for withdrawing from classes due to the pandemic. At the same time, many departments and instructors adopted more flexible grading policies to support student persistence and success during a challenging, online-only environment.

Despite these actions, the disruptions brought on by the pandemic have greatly impacted student enrollment and well-being. Similar to national trends, community college enrollment in California has dropped sharply, especially compared to four-year institutions, and most steeply among Black and Latino students (Brock and Diwa 2021, Bulman and Fairlie 2022; Linden et al. 2022). According to data from the Census Household Pulse Survey, four in ten households in California with a prospective or current community college student had cancelled their plan to enroll in post-secondary courses in fall 2020 (Belfield and Brock 2021).

Such trends expose the unique hurdles posed by the pandemic. Historically, community college enrollment has increased during economic downturns (Betts and McFarland 1995; Dundar et al. 2011; Barr and Turner 2013; Foote and Grosz 2020). Yet, the current tight labor market offers more opportunities than in the past, and wage increases among workers without a college education have incentivized labor force participation (Bauer et al. 2021).

At the same time, those who remained in community college weathered many challenges. Surveys conducted with California community college students suggest that more than half of students reduced their unit loads, faced decreases in work hours and income, and struggled to meet basic needs as a result of the pandemic, with Black and Latino students hit disproportionately hard (Reed et al. 2021; Nguyen et al. 2021).

Still, more work is needed to understand how pandemic-related changes have affected academic trajectories, especially among those seeking to transfer to a four-year institution—or more than half of all California students enrolled in community college. The transfer role is especially important for low-income students, first-generation college students, and students from underrepresented groups, all of whom are more likely to start their higher education journey in a community college.

At a national scale, the pandemic has led to steep declines in upward transfers to four-year colleges (Causey et al. 2022). In California, combined state community college transfers to University of California and California State University rose from fall 2019 to fall 2020, then fell from fall 2020 to fall 2021. The pandemic’s effects on transfers are only beginning to emerge, as community college enrollment continues to drop, and challenges continue to rise for current transfer-seeking students (Brohawn et al. 2021).

In this report, we identify and analyze the short-term effects of the pandemic on outcomes among transfer-intending students, analyzing trends in enrollment, success, and progress towards transfer through the fall 2021 term. In turn, we attempt to lay a strong foundation for future research on the pandemic’s impacts on longer-term academic trajectories as such data becomes available. To do so, we utilize longitudinal student-level data provided by the CCC Chancellor’s Office—this data covers the universe of students enrolled across all colleges in the system.

We begin by discussing how the pandemic affected enrollment among transfer-intending students, providing a brief descriptive analysis of fall term enrollment outcomes through 2021. Next, we analyze how the composition of transfer-intending cohorts changed over the same period, emphasizing changes in the demographics and academic histories of students declaring a transfer goal. These analyses are followed by a discussion on the effects of the pandemic on academic trajectories. First, we examine how the pandemic affected rates of enrollment and persistence in subsequent terms among already-enrolled transfer-intending students. We then look at success outcomes, analyzing how the pandemic affected the cumulative units that students attempted and earned, GPA, and progress towards transfer. We conclude with recommendations derived from our research.

The Pandemic and Community College Enrollment among Transfer-Intending Students

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit in the middle of the spring 2020 term, colleges immediately transitioned to an almost fully remote learning environment amid heightened concerns over the well-being, economic security, and health of students. The California Community Colleges system may have lost nearly 300,000 students from fall 2019 to fall 2021 as a result of these disruptions, according to recent research using administrative summary-level data (Bulman and Fairlie 2022). Losses varied widely among student groups and across community colleges (Linden et al. 2022).

While community college enrollment in California already had been declining in recent years—especially among transfer-intending students—the pandemic magnified the system’s challenges with attrition and retention. During the pandemic, enrollment drops among students with a transfer goal were, in aggregate, in line with declines among all students, or about 20 percent of students over two years—from fall 2019 to fall 2021. While enrollment dropped less steeply among transfer-intending students from fall 2019 to 2020, from fall 2020 to fall 2021 the decline was especially large in magnitude compared to students on an associate’s degree or career technical education (CTE) path. Such impacts on the size of transfer-intending cohorts may have longer-term implications on transfer volume and enrollment in California’s four-year institutions. In this section, we discuss and contextualize these enrollment trends.

The Pandemic Exacerbated Declines in Enrollment

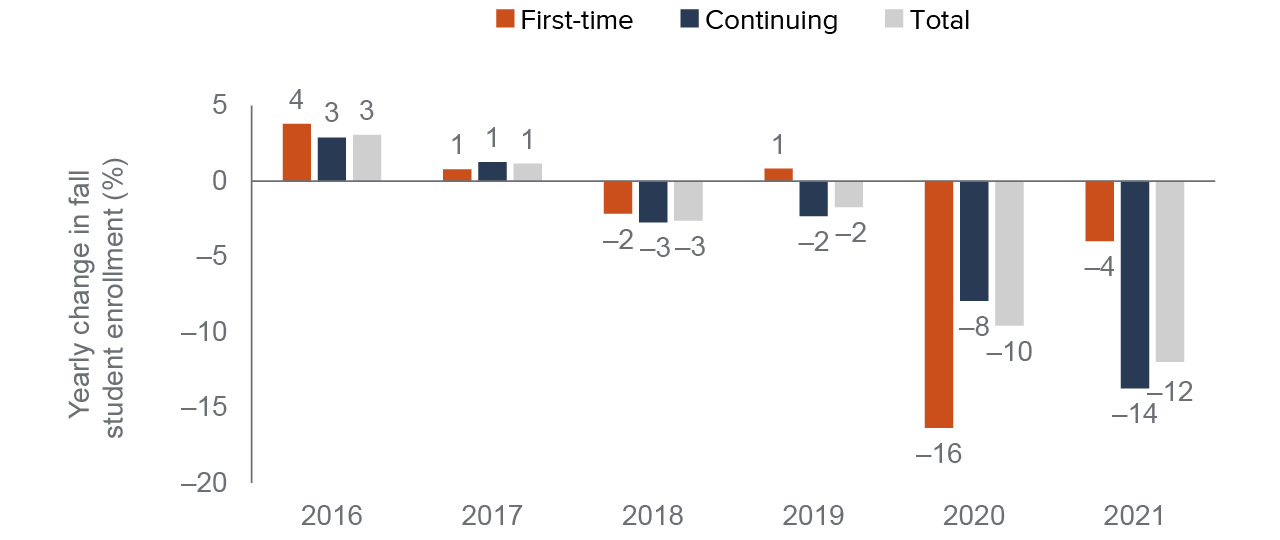

Enrollment declines among transfer-intending students fell into the double digits from fall 2019 to fall 2021—much steeper than previous declines, which had been 3 percent and 2 percent in the two years prior (Figure 1). Overall, 152,332 fewer transfer-intending students enrolled in fall 2021 (593,604) compared to fall 2019 (745,936).

While enrollment dropped more steeply among first-time students (16%) compared to continuing students (8%) from fall 2019 to fall 2020, counts for first-time students fell by only 4 percent in the following year. Among continuing students, enrollment fell by 14 percent. It is possible that many would-be first-time students who delayed enrolling in fall 2020 enrolled the following fall, leading to a smaller decline from fall 2020 to fall 2021.

Fall enrollment dropped sharply for continuing and first-time transfer-intending students during the pandemic

SOURCE: Authors’ calculations using MIS data.

NOTES: Fall term of each year. Restricted to transfer-intending students who enrolled in at least one credit course in the fall term of interest. Excludes enrollments from special-admit students. See Technical Appendix Tables C1 and E4 for student counts and percent changes.

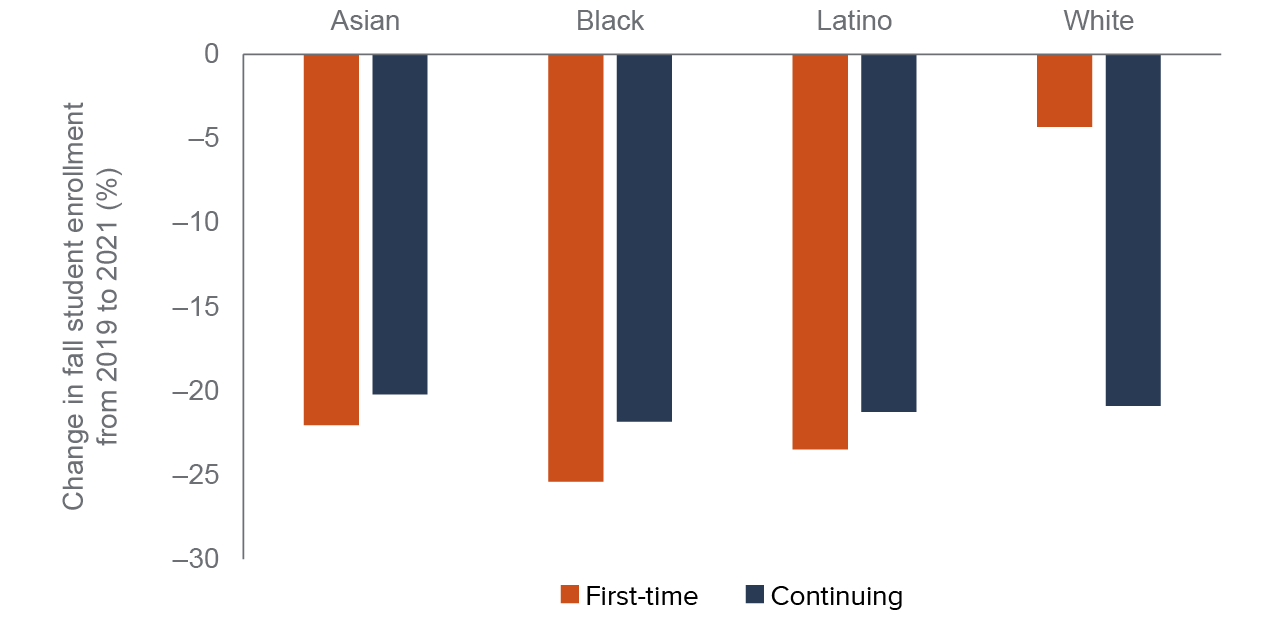

While enrollment drops were steep across the board, declines were slightly steeper among Black and Latino students, most noticeably from fall 2019 to 2020 (see Technical Appendix Table C2). The relatively large drop in Latino enrollment is especially concerning: year-over-year enrollment among Latino students had been holding steady or rising before the pandemic, while enrollment had been falling among white and Asian students.

In aggregate, enrollment declines were similar across racial and ethnic groups from fall 2019 to fall 2021, especially among continuing students (see Figure 2 and Technical Appendix Table C4). Among first-time students, however, declines were uneven. For almost all demographic groups, aggregate first-time student counts fell by at least 22 percent; but among first-time white students, enrollment was only 4 percent lower in fall 2021 than it was before the pandemic (see Technical Appendix Table C3).

Enrollment declines were large for all transfer-intending students, but much less pronounced among first-time white students

SOURCE: Authors’ calculations using MIS data.

NOTES: Percent change in enrollment from fall 2019 to fall 2021. Restricted to transfer-intending students who enrolled in at least one credit course in the fall term of interest. Excludes enrollments from special-admit students. See Appendix Tables C2, C3, and C4 for student counts.

Despite these large impacts on enrollment, the share of all initially enrolled students declaring a transfer goal has remained steady over time (see Technical Appendix Table C1). At the beginning of the fall 2019 term, 57 percent of students who enrolled in at least one credit course stated a transfer goal. In fall 2020 and 2021, 59 and 57 percent did so, respectively. Furthermore, the share of all first-time students who declared a transfer goal remained constant, as did the share among continuing students. Thus, the pandemic did not seem to change the academic goals of students who followed through on their plans to enroll in community college.

Enrollment Declines Were Large among Non-white Students, Especially Considering Pre-pandemic Trends

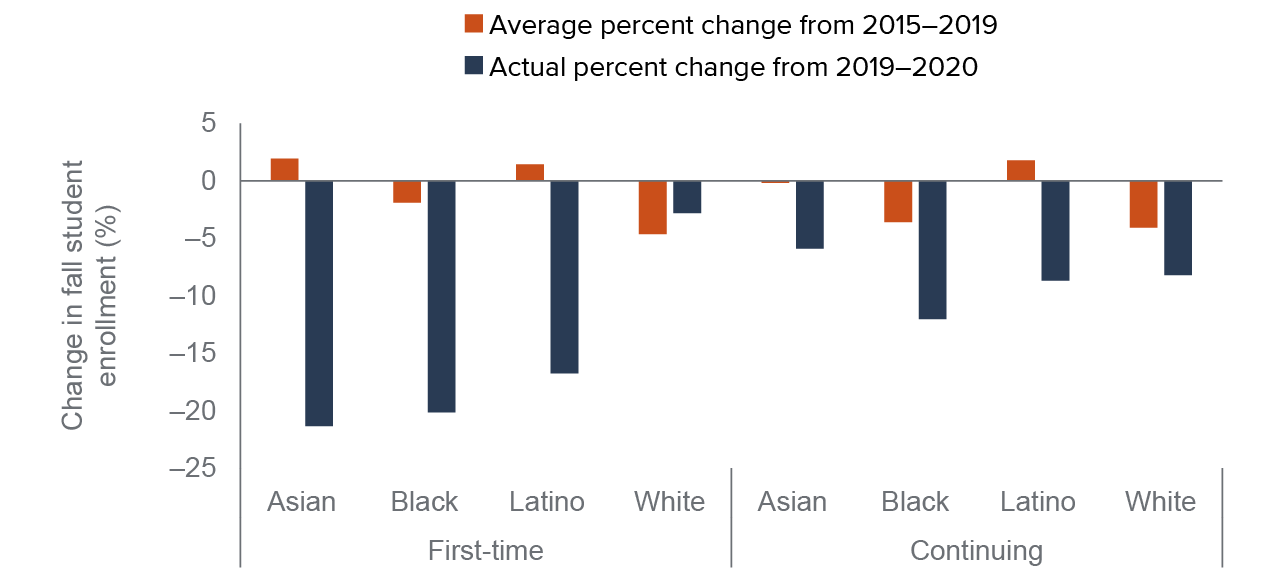

Historically underrepresented students, including Black and Latino students, were likely overrepresented among those who ultimately did not enroll during the pandemic, given the disproportionate impact on enrollment. For comparison, we can estimate the non-pandemic change we would have expected among different groups for fall 2019 to fall 2020 if we assume that changes in the student population would have followed recent trends, and average the yearly percent changes in enrollment from fall 2015 to 2019 (see Technical Appendix Table C5).

Gaps are largest among first-time Asian, Black, and Latino students when we compare the pre-pandemic average with actual percent changes from fall 2019 to 2020 (Figure 3). Among continuing students, gaps are largest among Black and Latino students.

Given that counts for first-time white students were falling before the pandemic, enrollment for this group was actually higher in fall 2020 than would have been expected—the drop in enrollment from fall 2019 to fall 2020 was less steep than otherwise predicted under non-pandemic circumstances.

Such disproportionate outcomes are exacerbated by pre-pandemic trends in enrollment. Among first-time and continuing Latino students, large gaps occur between expected and actual percent changes. These gaps capture that Latino enrollment had been steadily rising before the pandemic—pre-pandemic enrollment projections would estimate higher student counts in fall 2020. At the same time, Latino enrollment fell disproportionately during the pandemic. Thus, disparities between actual and expected student counts are extreme for this group; this is similarly the case among first-time Asian students.

Gaps between expected and actual percent changes in enrollment during the pandemic were highest among non-white students

SOURCE: Authors’ calculations using MIS data.

NOTES: Restricted to transfer-intending students who enrolled in at least one credit course in the fall term of interest. Excludes enrollments from special-admit students. See Technical Appendix Table C5 for calculations. See Technical Appendix Tables C2, C3, and C4 for student counts.

The Pandemic and the Composition of Transfer-Intending Cohorts

Students who intend to transfer make up a majority of enrollments at California community colleges (around 57%). The transfer pathway is especially important for Black, Latino, low-income, and first-generation students, all of whom are more likely to start their higher education journey in a community college. Considering that such students were more likely to not enroll during the pandemic, this disparity could greatly alter the composition of current and future transfer-intending cohorts—in effect, widening equity gaps in transfer progress and attainment.

In this section, we analyze changes in the demographic composition of transfer-intending cohorts over time, with emphasis on differences between students enrolled in fall terms before the pandemic (from 2015 to 2019) and students enrolled during the pandemic (fall 2020 and fall 2021).

Demographic Composition Remained Relatively Stable

Despite disproportionate enrollment drops across student groups, the composition of transfer-intending students who did enroll remained relatively unchanged through the pandemic. This is primarily because overall enrollment counts are large enough—and declines across groups spread out enough—that disproportionate drops among certain groups led to only a slight shift in composition. This stability is especially apparent when we analyze enrollment shares among groups that account for an already-small share of transfer-intending students before the pandemic, such as Black students.

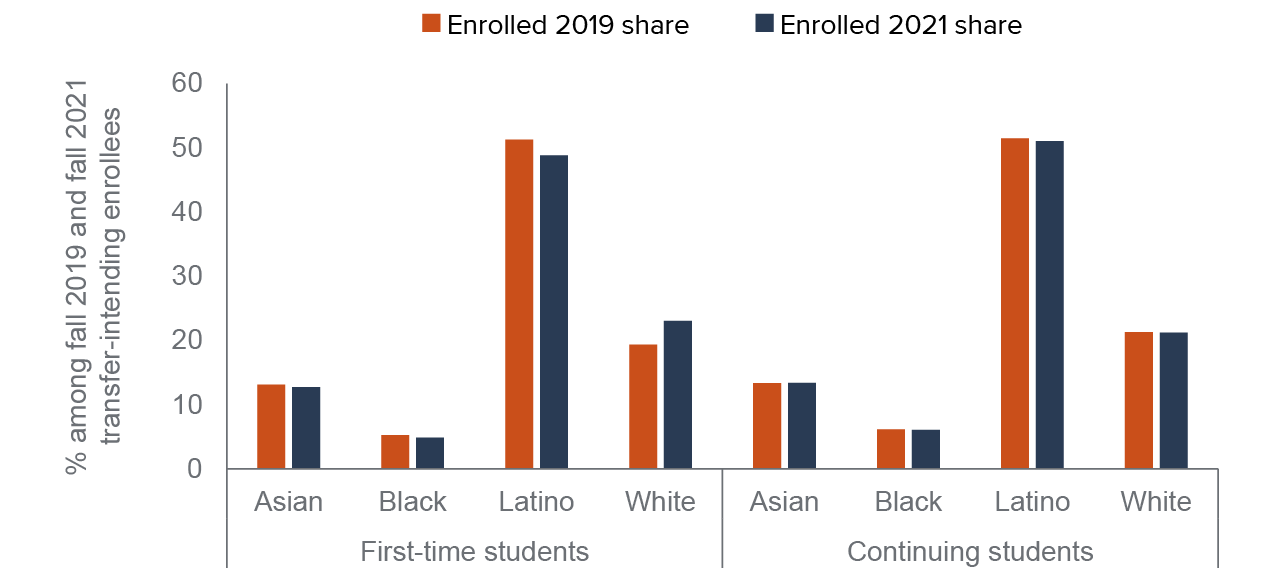

Shares changed very little among groups with larger pre-pandemic enrollment. Despite sharp drops in student counts, Latinos continued to account for a similar share of first-time and continuing students in fall 2020 and 2021 as they did among prior cohorts (Figure 4). Notably, the share of first-time white students rose from 19 percent in fall 2019 to 23 percent in fall 2021. As discussed in the previous section, enrollment declines among such students were disproportionately low during the pandemic, especially considering that white student counts had been steadily decreasing in the years prior to the pandemic.

Overall, compositional shares—including by race and ethnicity, gender, education level, age, first-generation status, and various other student demographics—were very similar among students who enrolled in fall 2020 and fall 2021 compared to those who enrolled in fall 2019 and the years prior (see Technical Appendix Table C6). However, enrollment declines were not equal across student groups, and thus, even slight drops in enrollment shares among underrepresented groups may lead to significant disparities in future enrollment and transfer counts.

The racial/ethnic composition of enrolled transfer-intending students was similar before and during the pandemic

SOURCE: Authors’ calculations using MIS data.

NOTES: Fall term of each year. Restricted to transfer-intending students who enrolled in at least one credit course in the fall term of interest. Excludes enrollments from special-admit students. See Technical Appendix Table C6 for student counts and more detailed compositional shares.

Academic Progress toward Transfer Had Been Improving among Continuing Students before the Pandemic

Understanding who was more likely to succeed and make progress towards their transfer goals also involves determining how less-observable characteristics among the enrolled changed as a result of the pandemic. Using extensive information on outcomes among students who previously enrolled in the community college system, we can analyze how progress towards transfer—in the form of unit accumulation and rates of milestone achievement along the transfer pathway—changed among continuing students during the pandemic.

Of particular interest is whether transfer-intending students who enrolled during the pandemic (fall 2020 and fall 2021) looked different in terms of their community college history than students who enrolled in terms before the pandemic (fall 2016 to fall 2019). To answer this question, we compare pre-fall cumulated outcomes between continuing students enrolled across fall terms. We conduct this analysis separately for students by years since their first enrollment in the system; that is, we analyze students with experience ranging from one year in college to five or more years in college.

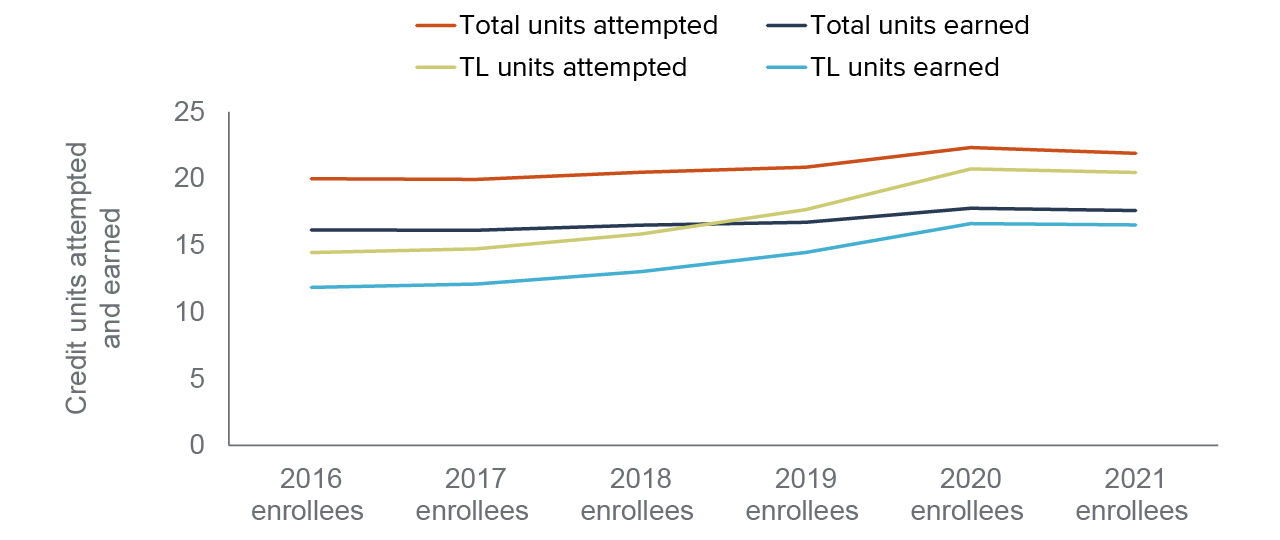

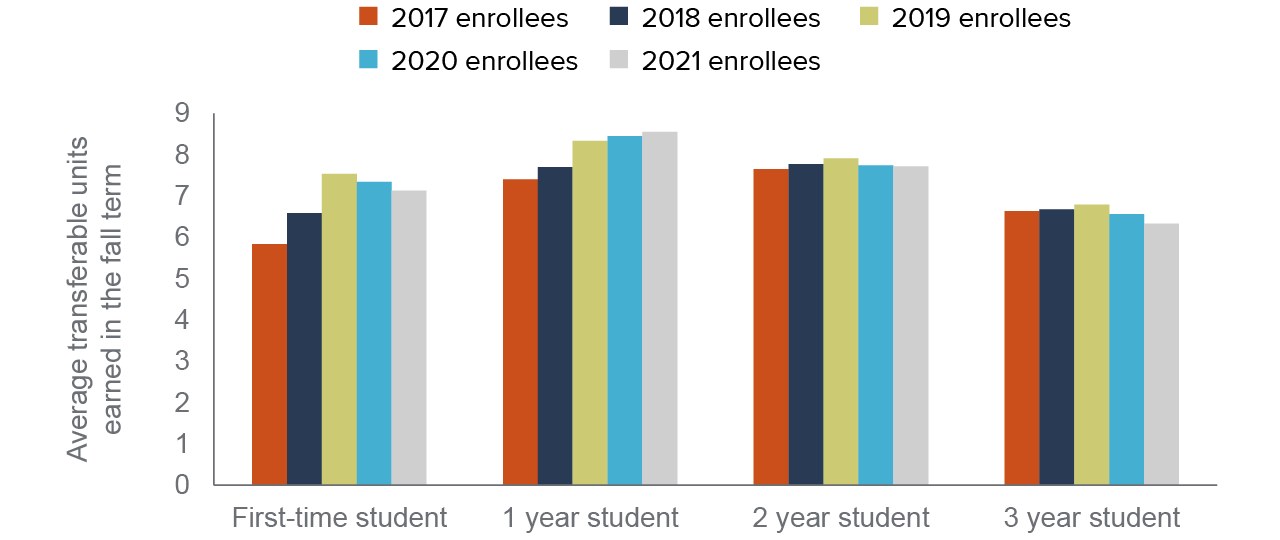

Students who enrolled during the pandemic had higher pre-fall average unit attempts, unit accumulation, and GPAs than students who enrolled before the pandemic, and this finding applies across all levels of experience in community college (see Technical Appendix Table C7). What’s more, continuing students arriving in the fall 2020 and 2021 terms had greater success in transfer-level coursework, attempting and earning a higher share of transferable units. While such gaps in achievement were large among all continuing students, the difference in transfer-level unit accumulation was largest among students with one year of experience (Figure 5).

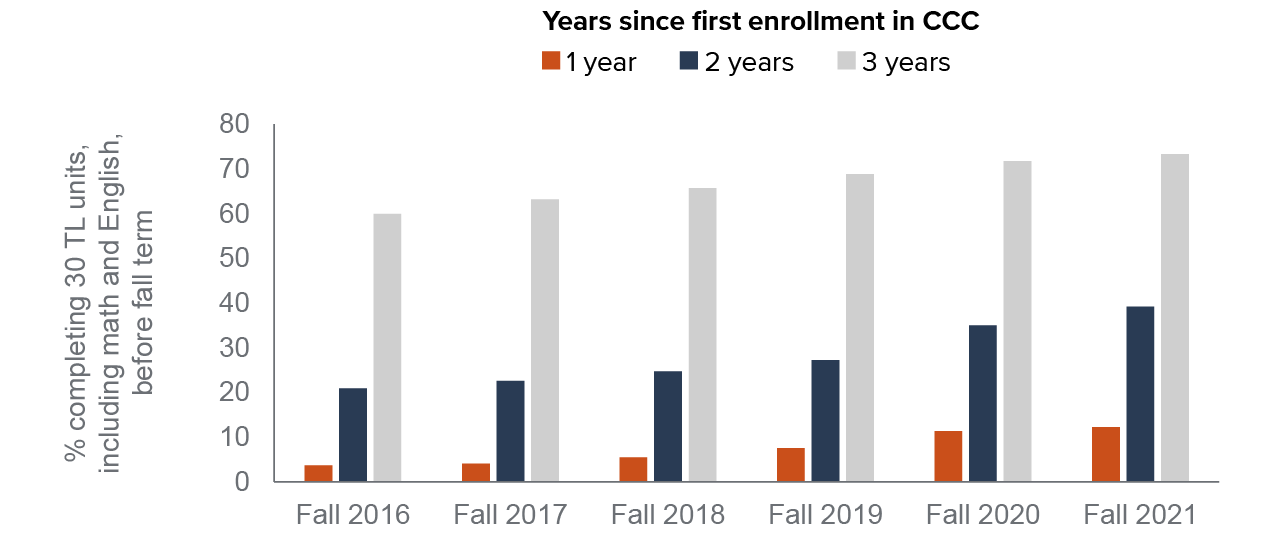

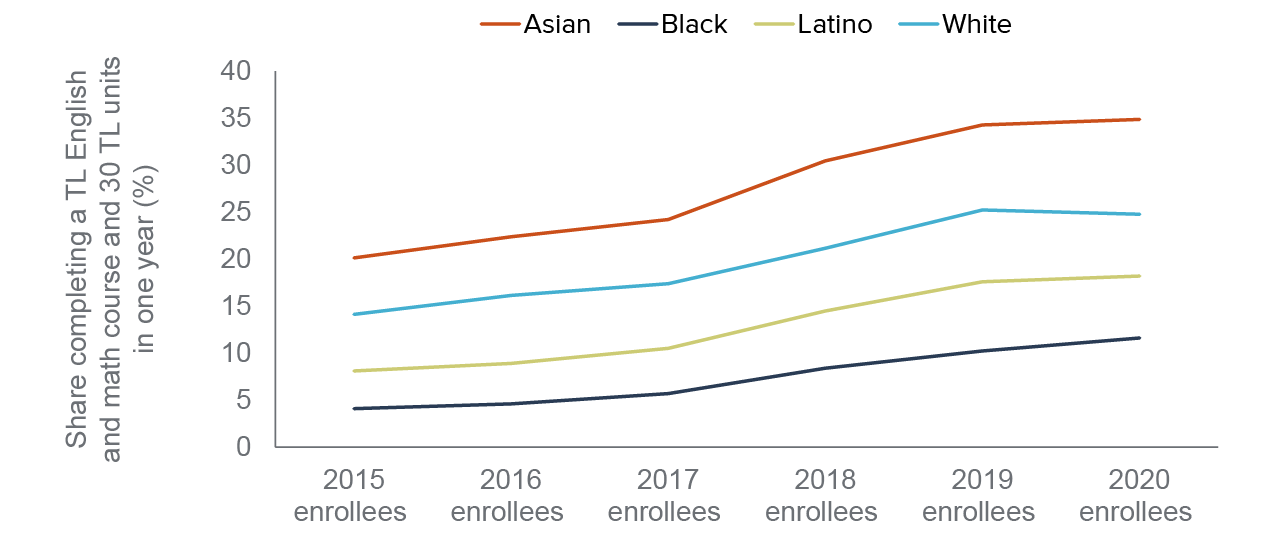

Furthermore, students who enrolled during the pandemic were more likely to meet certain academic milestones along the transfer pathway. Specifically, continuing students passed gateway transfer-level English and math courses at higher rates—and reached the critical milestone of completing at least 30 transferable units and both a transfer-level English and math course—compared to continuing students from non-pandemic terms (Figure 6).

However, academic progress towards transfer had already been improving before the pandemic started. That is, transfer-level unit accumulation and rates of milestone completion were increasing steadily for all fall cohorts from 2016 to 2019. Pre-pandemic reform efforts already underway across the community college system, such as the implementation of Assembly Bill (AB) 705, Guided Pathways and Associate Degree for Transfer (ADT), may explain such trends. Thus, the extent to which the pandemic limited access to community college for those with weaker academic backgrounds remains unclear.

Transfer-intending students with one year of experience in the community college system were increasing their attempts and accumulation of transfer-level units over time

SOURCE: Authors’ calculations using MIS data.

NOTES: Fall term of each year. Cumulated outcomes are up until the fall term of interest. Course transfer status (TL) indicates whether a course is transferable to UC and/or the CSU systems on the basis of articulation agreements. Restricted to first-time transfer-intending students who enrolled in at least one credit course in the fall term of interest. Excludes enrollments from special-admit students. Outcomes are restricted to those in credit courses. See Technical Appendix Table C7 for more detailed information on students’ academic histories, including outcomes from continuing students with earlier enrollments in the community college system.

It is still very likely that the students who showed up in the fall during the pandemic do look quite different—in unobservable or less-apparent characteristics such as motivation, academic preparation, skills, needs, and resources—to their counterparts enrolled across previous fall terms. Though levels of transfer-level unit accumulation and progress towards transfer among enrolled students had been trending upwards before the pandemic, the composition of enrollees during the pandemic may have been particularly selective, and students needing more support may have been disproportionately left behind. In the text box below, we highlight insights from our interviews with faculty that shed light on some of these concerns.

The Pandemic and Persistence across Terms among Transfer-Intending Students

In addition to enrollment declines, the pandemic also may have exacerbated problems with persistence and course success among already-enrolled transfer-intending students at California’s community colleges. As we learned from our interviews with faculty, many students who were able to initially enroll during the pandemic found it difficult to successfully complete their courses. Some students faced economic hardships and many struggled with the online setting, especially those that did not have the required resources, such as a computer, internet access, or appropriate space to study effectively. In fact, a significant share of students—particularly among those enrolled in earlier terms of the pandemic—dropped some or all of their courses entirely, with most able to take advantage of systemwide flexibilities on course withdrawals.

Rates of persistence—or enrollment across multiple terms—declined by 5 percent among all community college students, varying greatly across colleges and across student groups (Linden et al. 2022). Such impact may have longer-term implications on students’ ability to make progress toward their transfer goals and on four-year universities awaiting transfer students over the next few years.

In this section, we analyze how persistence and course success across terms changed among already-enrolled transfer-intending students. We focus on students enrolled in fall terms and examine their enrollment outcomes in subsequent terms, with emphasis on differences in persistence and course success rates in fall terms during the pandemic (2020 and 2021) compared to terms before the pandemic.

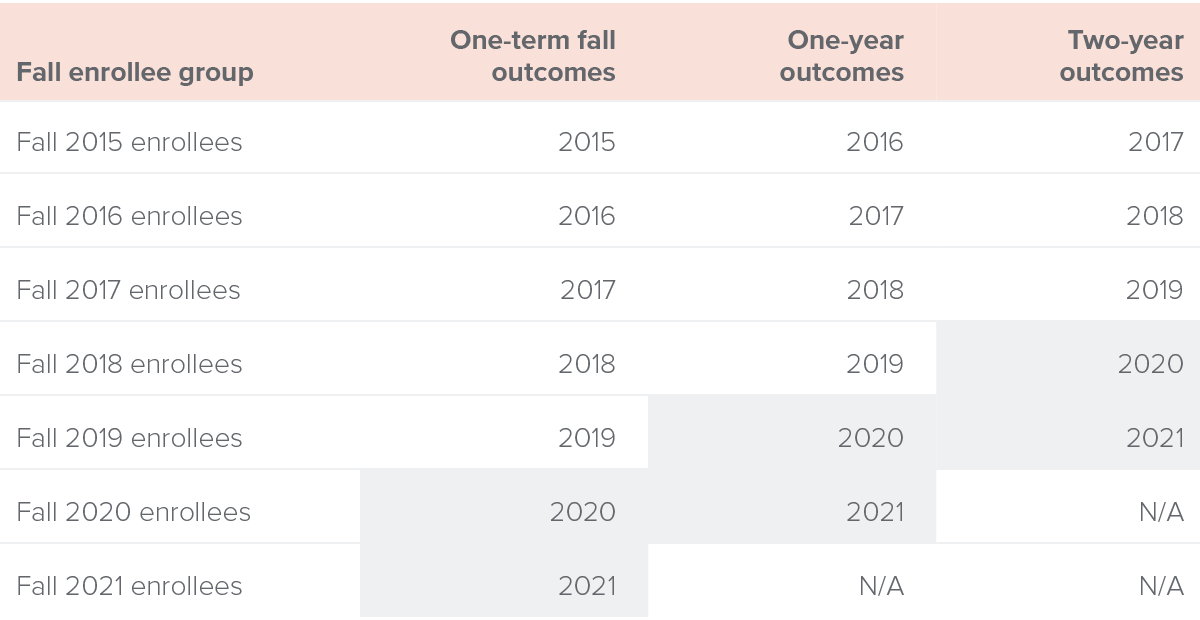

In these analyses, we attempt to more accurately compare students who experienced the pandemic in their subsequent term enrollments to similar students who did not experience the pandemic. We do this by controlling for a variety of student demographics and characteristics, including their time enrolled in community college, their race and ethnicity, and their pre-fall academic outcomes. Table 1 outlines which groups of fall-enrolled students we identify as “pandemic-affected” according to our outcome of interest, meaning their outcomes overlap with the fall 2020 and/or fall 2021 terms.

Fall enrollee groups whose one-term, one-year, and two-year outcomes were affected by the pandemic enrolled in a CCC in fall 2018 through fall 2021

SOURCE: Authors’ calculations using MIS data.

NOTES: Highlighted cells indicate fall enrollee groups of transfer-intending students whose selected outcomes are affected by the pandemic, meaning they overlap with the fall 2020 and/or fall 2021 terms. One-term outcomes among fall 2020 and 2021 enrollees occurred during the pandemic. One-year (fall-to-next fall) outcomes among fall 2019 and 2020 enrollees overlap with pandemic terms. Two-year (fall-to-second fall) outcomes among fall 2018 and 2019 enrollees overlap with pandemic terms. Fall enrollees include both first-time and continuing students. N/A indicates that the respective fall enrollee group is excluded from the analysis due to data constraints. For example, given that our data only provides student outcomes up until the fall 2021 term, we are unable to present one year outcomes for the group of students enrolled in fall 2021.

Persistence and Success in Subsequent Terms Fell Modestly

Before the pandemic, students had relatively stable rates of enrolling in subsequent terms and successfully completing at least one course in the term. On average, about 82 percent of all students who enrolled in a fall term before 2020 successfully completed at least one course that fall. About 60 percent consistently enrolled in fall the next year—and 50 percent completed a course in that term. Subsequently, 42 percent dependably re-enrolled two years later, and 34 percent completed a course.

For students enrolled during the pandemic, the average share who successfully completed at least one course was 4 percentage points lower compared to students enrolled before the pandemic. One year later, average rates of enrollment and successful course completion each declined by 5 percentage points—that is, fall 2019 and 2020 students were 5 percentage points less likely to enroll and to complete at least one course in the following fall terms than those who had not experienced the pandemic. Similarly, enrollment and course completion two years later was 5 percentage points lower for students affected by the pandemic (fall 2018 and 2019 enrollees, respectively) (see Technical Appendix Table C8).

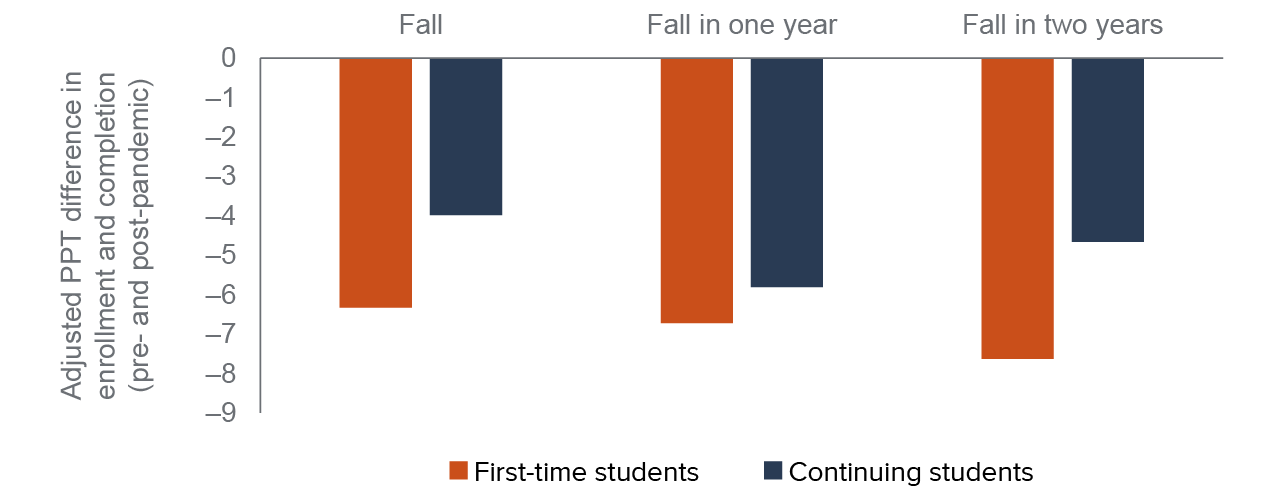

After controlling for demographics and academic histories among continuing students, our results were consistent with the raw gaps in enrollment and course completion between pre-pandemic and pandemic-impacted terms. First-time students impacted by the pandemic were 6.3 percentage points less likely to successfully complete at least one course in the fall (Figure 7) than those not affected by the pandemic. Considering an overall baseline of about 82 percent before the pandemic, it’s a modest drop in success for students enrolled in fall 2020 and 2021.

Outcomes one year and two years out show gaps of about 6.7 and 7.6 percentage points, for enrollment and course completion, respectively. Given that before the pandemic, average enrollment rates and course completion were already lower after one year (57% for first-time students) and after two years (42% for first-time students), such declines are relatively more significant than they were for one-term fall outcomes.

Continuing students show a generally smaller gap in course completion between pandemic- and pre-pandemic terms—between a 4- and 6-percentage-point difference for one-term fall, one-year, and two-year differences. Nevertheless, declines in persistence and successful course completion were statistically significant and modest in magnitude among all students.

First-time transfer-intending students were especially less likely to enroll in and complete a course during terms impacted by COVID

SOURCE: Authors’ calculations using MIS data.

NOTES: Each estimated difference comes from separate regressions comparing those enrolled in pandemic-impacted terms to those in pre-pandemic terms. Outcomes represent successful completion of at least one credit course in a given term: in the fall, in one year (one fall term later), and in two years (two fall terms later). Regressions for continuing students include academic characteristics prior to the first fall. Those are not available for first-time students, as they have no course history at CCC before their first term. All regressions include campus fixed effects and demographic characteristics including gender, education level, race, Pell Grant status, foster status, age, and prior dual enrollment. Restricted to transfer-intending students who enrolled in at least one credit course in the fall term of interest. Excludes enrollments from special-admit students. Full regression results for first-time students are presented in Technical Appendix Tables D1, D2, and D3. Results for continuing students are presented in Technical Appendix Tables D4, D5, and D6.

Declines Were Highest among Latino and Newer Continuing Students

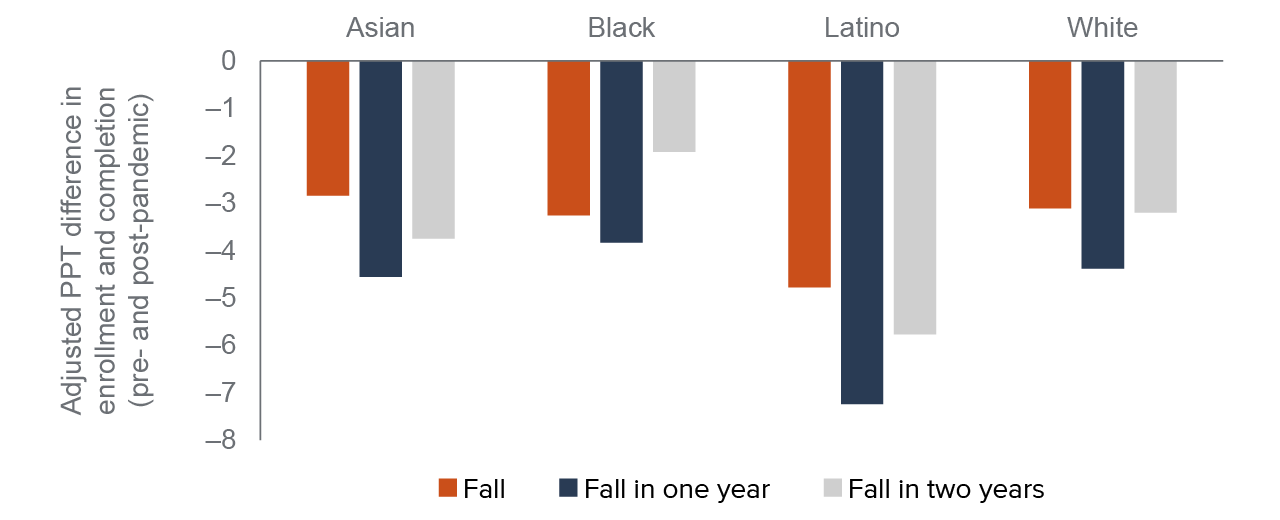

Declines in rates of enrollment and course completion during the pandemic were not equally distributed across student groups (see Technical Appendix Table C8). While transfer-intending students in every racial and ethnic group were less likely to enroll and successfully complete a course in fall 2020 and 2021, Latino students affected by the pandemic experienced the largest drop when compared to Latino students not affected by the pandemic. Continuing Latinos enrolled in pandemic-affected terms saw a 4.7 percentage point drop in the share of students successfully completing at least one course in the fall compared to similar Latino students in non-pandemic terms. Continuing Asian, Black, and white students, on average, saw drops of about 3 percentage points in the fall (Figure 8). The same pattern holds true, and gaps were larger, for Latino student enrollment and course completion after one and two years.

Continuing transfer-intending Latino students, in particular, saw sharp declines in persistence compared to similar pre-pandemic Latino students

SOURCE: Authors’ calculations using MIS data.

NOTES: Each estimated difference comes from separate regressions comparing those enrolled in pandemic-impacted terms to those in pre-pandemic terms among students within the same racial or ethnic group. Outcomes represent successful completion of at least one credit course in a given term: in the fall, in one year (one fall term later), and in two years (two fall terms later). Regressions include academic characteristics prior to the first fall. All regressions also include campus fixed effects and demographic characteristics including gender, education level, Pell Grant status, foster status, age, and prior dual enrollment. Restricted to continuing transfer-intending students who enrolled in at least one credit course in the fall term of interest. Excludes enrollments from special-admit students. Full regression results for the interacted regressions for continuing students are presented in Technical Appendix Tables D7, D8, and D9.

Even though the impact by percentage points on two-year (fall-to-second fall) outcomes was lower for all groups compared to one-year (fall-to-next fall) outcomes, on average students are more likely to return and successfully complete at least one course in the next year (50%) than in two years (32%). Accordingly, a 6-percentage-point drop in one-year enrollment and successful course completion represents a 10 percent change, which is about in line with a 4-percentage-point drop in two-year enrollment and successful course completion.

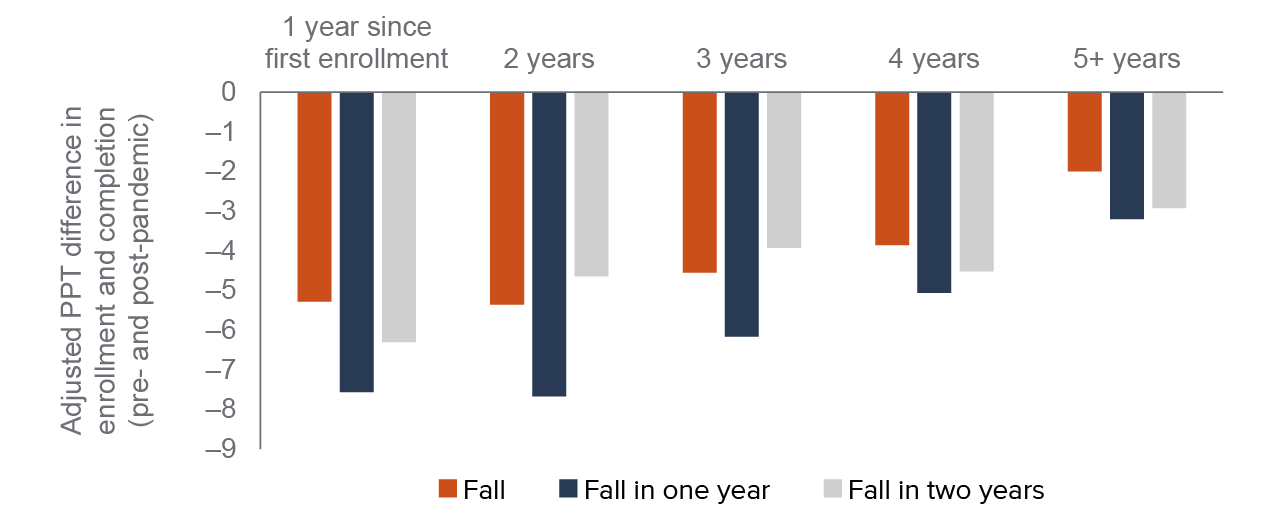

Aside from first-time students, continuing students with less community college experience faced the largest declines in the share successfully completing at least one course in the fall, next year, and second year. During the pandemic, continuing students were less likely to re-enroll and successfully complete at least one course compared with otherwise similar continuing students not affected by the pandemic, regardless of how long ago they first enrolled in community college. However, those who enrolled more recently saw bigger percentage-point differences between pandemic and non-pandemic cohorts than those who had first enrolled in community college three or more years prior (Figure 9).

Newer continuing students were less likely to re-enroll and complete a course during the pandemic

SOURCE: Authors’ calculations using MIS data.

NOTES: Each estimated difference comes from separate regressions comparing those enrolled in pandemic-impacted terms to those in pre-pandemic terms among students with the same number of years since their first enrollment in the community college system. Outcomes represent successful completion of at least one credit course in a given term: in the fall, in one year (one fall term later), and in two years (two fall terms later). Regressions include academic characteristics prior to the first fall. All regressions also include campus fixed effects and demographic characteristics including gender, education level, race, Pell Grant status, foster status, age, and prior dual enrollment. Restricted to continuing transfer-intending students who enrolled in at least one credit course in the fall term of interest. Excludes enrollments from special-admit students. Full regression results for the interacted regressions for continuing students are presented in Technical Appendix Tables D10, D11, and D12.

The Pandemic Magnified Pre-existing Issues with Persistence and Success

Drops in persistence further exacerbated other gaps between racial and ethnic groups. Latino and Black students affected by the pandemic were disproportionately represented among first-time students who did not successfully complete at least one course in the fall, next year, and second year (see Technical Appendix Table C9). Among continuing students, Black and Latino students similarly account for a large share who were not successful in the fall (see Technical Appendix Table C10).

However, these disparities are not new—Black and Latino students in pre-pandemic cohorts were also less likely to successfully complete a course in any given term. Thus, outcomes during the pandemic mostly reflect inequities that were already apparent in the years prior.

When we compare academic histories, similar gaps in academic achievement appear among all continuing students, before and during the pandemic. Students who successfully completed a course in the fall and in subsequent terms had stronger academic backgrounds than students who did not—including prior cumulative unit accumulation, GPA, and rates of completion of transfer-level coursework (see Technical Appendix Tables C11, C12, and C13). Such outcomes are most apparent when we examine one-term fall outcomes and outcomes among students with less community college experience. These gaps were similar among pandemic-affected students compared to pre-pandemic students; however, pandemic-affected students had stronger prior academic achievement. Students who were successful during the pandemic had much greater unit accumulation and were much more likely to complete transfer-level coursework than successful students who were enrolled before the pandemic.

Overall, the pandemic exacerbated pre-existing issues with persistence. Rates of enrollment and successful course completion across subsequent terms were already relatively low before the pandemic. Considering that all our estimates above exclude students who transferred, a substantial share of students who do not transfer have not been persisting into, much less succeeding in, subsequent terms.

Before the pandemic, 18 percent of fall-enrolled students were not successfully completing at least one course, half were not completing a course in the next year, and two-thirds were not doing so two years later. During the pandemic, rates of success dropped only further and changes were particularly large for first-time and Latino students.

Furthermore, though pandemic-induced declines among Black students were relatively small, rates of persistence and successful course completion were already relatively low among such students before the pandemic. Thus, gaps in success remained wide. The inequitable distribution of successful students long predates the pandemic, with Black and Latino students accounting for a disproportionate share of students unable to successfully complete one course in a given term.

The Pandemic and the Academic Progress of Transfer-Intending Students

Course-level and cumulative outcomes among transfer-intending students were improving before the pandemic. Still, many students were not ultimately enrolling in a four-year institution. Overall, transfer rates are highest among students that reach certain unit- and course-completion milestones, especially within a shorter time. Among California community college students, transfer rates are highest among those who successfully complete gateway transfer-level math or accumulate 30 or more transferable units in their first year. Furthermore, about 60 percent of transfer students earn 60 transferable units or more and 9 in 10 of such students successfully completed both a transfer-level math and English course (Johnson and Cuellar Mejia 2020).

The pandemic’s effects on enrollment, persistence, and course completion may have stalled progress towards transfer, at the very least, extending the time it takes students to transition to a four-year institution. More concerning is the potential decline in students who eventually reach key academic milestones. These declines may have set California’s higher education system back in providing UC and CSU campuses with sufficient transfer-eligible students. Such negative effects would limit the system’s ability to promote economic mobility among historically underrepresented students who disproportionately rely on the transfer pathway.

In this section, we conclude our analysis on the pandemic’s impacts on student outcomes by analyzing how unit accumulation and progress towards transfer changed among already-enrolled transfer-intending students. We focus on students enrolled in fall terms and examine their one-term, cumulative one-year, and cumulative two-year outcomes, with emphasis on average differences between students whose respective trajectories were affected by the pandemic (overlapping with the fall 2020 and/or 2021 terms) compared to those whose trajectories did not overlap with pandemic-affected terms. In order to make comparisons between similar students, we continue to control for a variety of student demographics and characteristics, including their time enrolled in community college, their race and ethnicity, and their pre-fall academic outcomes.

Students Retained Pre-pandemic Progress on Accumulating Units

Before the pandemic, the average number of cumulative transferable units attempted and earned in one term, one year, and two years was increasing slightly for first-time and continuing students (see Technical Appendix Tables C14 and C16). While units attempted fell among students affected by the pandemic (fall 2020 and 2021 enrollees), when compared with the most recent cohort of pre-pandemic students (fall 2019 enrollees), the declines were very small, and students retained most of the progress made leading up to the pandemic. The change in one-term and cumulative transferable units earned was even smaller (Figure 10).

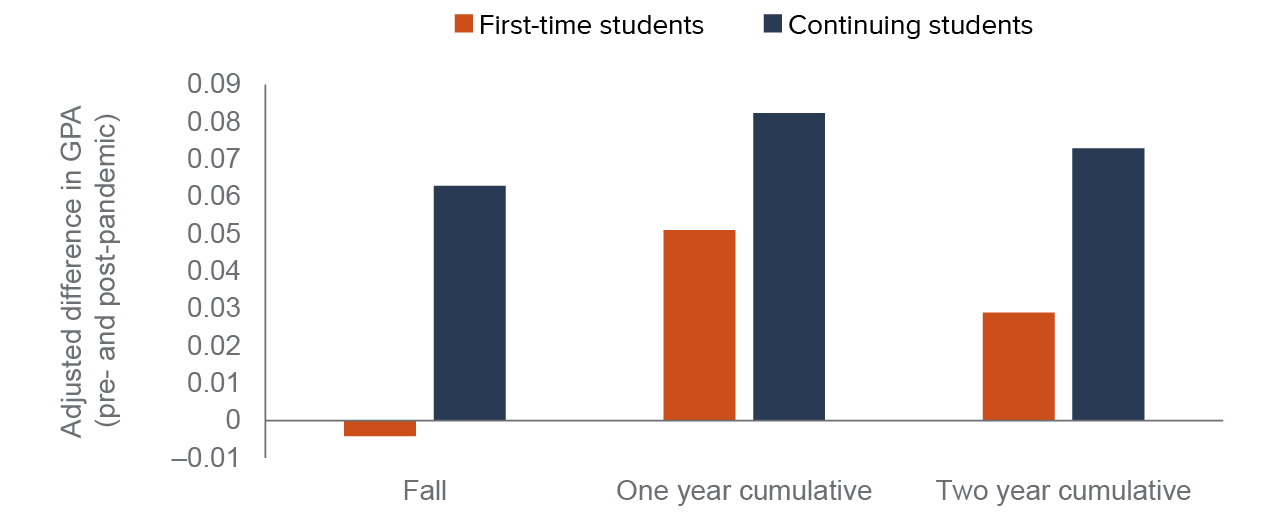

Thus the pandemic seems to have had minimal effects on unit accumulation among already-enrolled transfer-intending students. At the same time, fall and cumulative GPAs were higher among students affected by the pandemic (see Technical Appendix Table C18). While GPAs were trending upward, increased flexibility and changes to grading practices during the pandemic may have inflated grades for some students who were able to remain enrolled.

One-term unit accumulation did not change for transfer-intending students enrolled during the pandemic

SOURCE: Authors’ calculations using MIS data.

NOTES: Outcomes represent one-term unit accumulation in the fall term of interest. Years indicate years since first enrollment in the community college system. Course transfer status indicates whether a course is transferable to UC and/or the CSU systems on the basis of articulation agreements. Restricted to transfer-intending students who enrolled in at least one credit course in the fall term of interest. Excludes enrollments from special-admit students. Outcomes are restricted to those in credit courses. See Technical Appendix Table C16 for more detailed information on one-term, one-year, and two-year unit accumulation over time and through the pandemic.

First-time students affected by the pandemic were likely to earn about one to two cumulative units more compared to similar pre-pandemic students, after controlling for demographic characteristics (see Technical Appendix Tables D1, D2, and D3). This is likely because the timing of AB 705—which greatly changed placement rules around remediation at California community colleges—overlaps with the start of the pandemic. Statewide implementation of AB 705 began in 2019, and some colleges had already started implementing their own reforms in the years prior. Accordingly, enrollment and success in transfer-level math rose sharply, access to transfer-level English was nearly universal, and earned units climbed—even during the pandemic.

On the flip side, fall unit accumulation lessened for continuing students, when compared to similar students in pre-pandemic terms, and shrank further over two years (fall to second fall), at about .75 transferrable units. However, given that the mean continuing student earns about 21 transferrable units in two years, that represents a small difference overall.

The grades students earned were generally higher during the pandemic, even when accounting for academic differences in who persisted and enrolled in subsequent terms (Figure 11). Aside from first-time students in the fall, cumulative GPAs improved for almost all students enrolled during pandemic terms compared to similar students only enrolled in pre-pandemic terms. However, the differences were small, from essentially zero for first-time students in their first term, to about 0.08 grade points for continuing students from fall-to-fall. With a mean GPA of about 2.5, that represents about a 3 percent difference in overall GPA.

One-term and cumulative GPAs were generally slightly higher for transfer-intending students enrolled during the pandemic

SOURCE: Authors’ calculations using MIS data.

NOTES: Each estimated difference comes from separate regressions comparing those enrolled in pandemic-impacted terms to those in pre-pandemic terms. Outcomes represent cumulative GPA: in the fall, in one year (from fall to one fall term later), and in two years (from fall to two fall terms later). Regressions for continuing students include academic characteristics prior to the first fall. Those are not available for first-time students, as they have no course history at CCC before their first term. All regressions include campus fixed effects and demographic characteristics including gender, education level, race, Pell Grant status, foster status, age, and prior dual enrollment. Restricted to transfer-intending students who enrolled in at least one credit course in the fall term of interest. Excludes enrollments from special-admit students. Full regression results for first-time students are presented in Technical Appendix Tables D1, D2, and D3. Results for continuing students are presented in Technical Appendix Tables D4, D5, and D6.

Disparities in Unit Accumulation and Course Performance Were Minimal

For all students, cumulative transferable units earned did not fall much. While students with different community college experience attempted and earned one-term, cumulative one-year, and two-year units at markedly different levels, such gaps predate the pandemic and were not meaningfully widened among students whose trajectories overlapped with the fall 2020 and 2021 terms (see Technical Appendix Tables C14 and C16). Similarly, differences in cumulative GPA were not very different across such student groups. Continuing students enrolled longer saw minor positive differences in GPA compared to newer enrollees, but all differences were well under one-tenth of a grade point (see Technical Appendix Table C18).

Disparities in unit accumulation and GPA were also minimal across racial and ethnic groups (see Technical Appendix Tables C15, C17, and C19). While the students who were able to persist during the pandemic were those with stronger academic histories, small effects on academic progress among such students also may have been a result of increased grading flexibility during the pandemic (see text box below).

Progress Toward Transfer Continued to Rise through the Pandemic

The share of first-time transfer-intending students who successfully completed a transfer-level math and English course, as well as 30 transferable units as of the following fall increased through the pandemic. Specifically, a higher share—and remarkably, despite enrollment declines, a larger number—of first-time students enrolled in fall 2019 and 2020 accomplished this milestone in one year compared to students enrolled in previous fall terms (see Technical Appendix Table C20).

Such trends hold when comparing two-year outcomes between pandemic-affected cohorts (students enrolled in fall 2018 and 2019) and non-pandemic-affected fall enrollees (see Technical Appendix Table C21). Furthermore, though pre-pandemic equity gaps across racial and ethnic groups remain, the share and number of first-time students completing a transfer-level English and math course and at least 30 transferable units increased for all groups during the pandemic (Figure 12).

First-time transfer-intending students whose fall-to-fall outcomes were affected by the pandemic continued to make significant progress towards transfer

SOURCE: Authors’ calculations using MIS data.

NOTES: Course transfer status (TL) indicates whether a course is transferable to UC and/or the CSU systems on the basis of articulation agreements. Transfer-level English courses are introductory college composition courses that fulfill English composition general education requirements for transfer to a four-year institution. Transfer-level math courses include college algebra, trigonometry, pre-calculus, finite math, applied calculus, statistics, liberal arts math, math for teachers and other quantitative reasoning courses that meet transfer requirements to UC or CSU systems. For one-year outcomes, the pandemic-affected group includes fall 2019 and 2020 enrollees. Furthermore, for our one-year outcomes we exclude students who transferred out of the community college system within one year. Restricted to first-time transfer-intending students who enrolled in at least one credit course in the fall term of interest. Excludes enrollments from special-admit students. Outcomes are restricted to those in transferable courses. See Technical Appendix Table C20 for student counts.

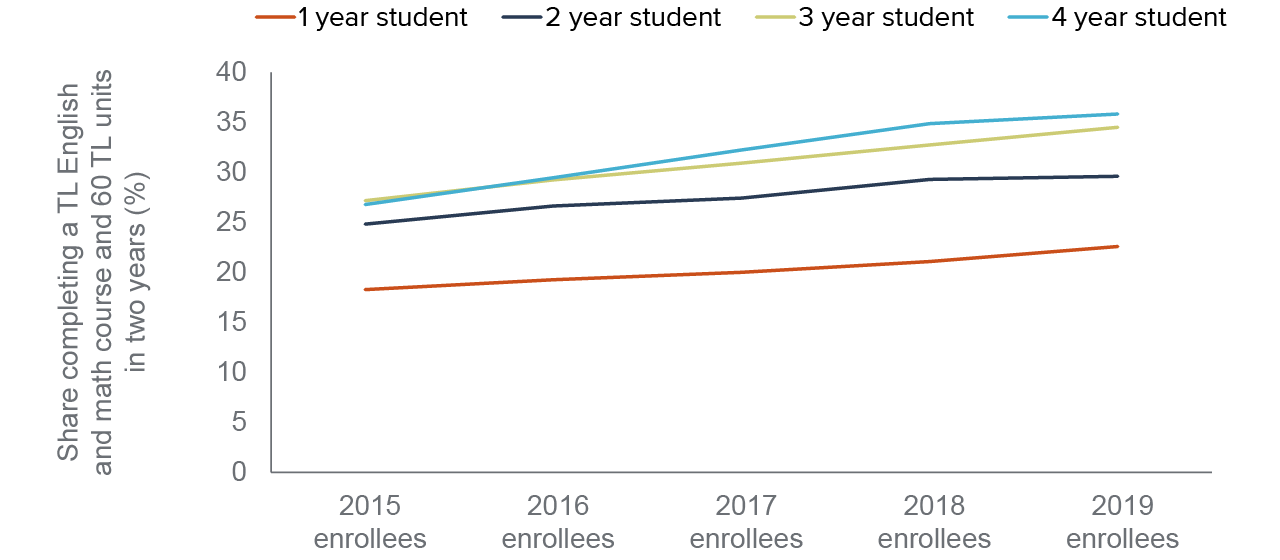

Similarly, continuing students were more likely to achieve transfer “readiness”—defined as earning at least 60 transferable units and completing both transfer-level English and math—in two years compared to their counterparts whose trajectories did not intersect with pandemic terms. Across students with different lengths of time since their first community college enrollment, the share reaching transfer “readiness” in two years increased over time, including through the pandemic (Figure 13). Specifically, a higher share of students enrolled in fall 2018 and fall 2019 accomplished this milestone as of the second fall (fall 2020 and fall 2021, respectively), than students whose two-year outcomes did not overlap with the pandemic. For the most part, the share and number of continuing students achieving key milestones along the transfer pathway increased for all racial and ethnic groups (see Technical Appendix Tables D22 and D23).

Continuing transfer-intending students whose outcomes were affected by the pandemic continued to make progress towards transfer

SOURCE: Authors’ calculations using MIS data.

NOTES: Years indicate years since first enrollment in the community college system. Course transfer status (TL) indicates whether a course is transferable to UC and/or the CSU systems on the basis of articulation agreements. Transfer-level English courses are introductory college composition courses that fulfill English composition general education requirements for transfer to a four-year institution. Transfer-level math courses include college algebra, trigonometry, pre-calculus, finite math, applied calculus, statistics, liberal arts math, math for teachers, and other quantitative reasoning courses that meet transfer requirements to UC or CSU systems. For two-year outcomes, the pandemic-affected group includes fall 2018 and 2019 enrollees. Furthermore, for our two-year outcomes we exclude students who transferred within two years. Restricted to continuing transfer-intending students who enrolled in at least one credit course in the fall term of interest. Excludes enrollments from special-admit students. Outcomes are restricted to those in transferable courses. See Technical Appendix Table C23 for student counts.

Promising policy reform efforts taking place before the pandemic, most notably the implementation of AB 705 in 2019, have undoubtedly widened opportunities for transfer-intending students to access and succeed in transfer-level coursework. Furthermore, as we’ve learned from our interviews with math and English faculty, equity-based department and classroom-level reforms have begun to take place across colleges, aiming to employ research-informed teaching strategies and create enhanced, student-centered learning environments for all students (Cuellar Mejia et al. 2021; Cuellar Mejia et al. 2022). Such efforts likely explain why we do not see large pandemic-induced negative effects on unit accumulation and milestone achievement among transfer-intending students, despite significant effects on enrollment and persistence across terms.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Our analyses suggest that large drops in enrollment during the pandemic may hurt the size, and perhaps the composition, of future transfer cohorts. Furthermore, modest drops in persistence rates, especially among first-time and Latino students, may stifle future transfer progress and attainment among newer cohorts.

At the same time, pre-pandemic initiatives aimed at improving unit accumulation and completion of transfer-level coursework, most notably AB 705, seem to have limited the negative effects of the pandemic on already-enrolled students. As the state transitions into a post-pandemic environment, collaborative efforts must be prioritized in order to improve enrollment, prevent future declines in transfer attainment, narrow equity gaps, strengthen and expand student supports and course offerings to meet student needs, and expand opportunities for institutional and external research.

Strengthen and Prioritize Strategies to Promote New Student Enrollment

Student enrollment in community colleges had been declining in the years prior to the pandemic. In order to prevent longer-term declines in the size and diversity of transfer cohorts, colleges, high schools, and the state must strengthen and prioritize collaborative efforts to expand outreach, recruitment, and enrollment.

The dual enrollment program known as College and Career Access Pathways (CCAP) is one initiative that was already bearing fruit pre-pandemic, enrolling equitable shares of Latino students and leading to higher enrollments in the California community colleges (Rodriguez and Gao 2021). The $250 million enacted in the governor’s 2022–2023 budget that expands dual enrollment and student supports is well-positioned to support these efforts. Furthermore, a dual admissions program, in which students who apply to and enroll in a community college are conditionally accepted to a four-year state university, could attract more community college applicants (Johnson 2021).

At the same time, efforts to increase new student enrollment must also focus on prospective adult students. While educational attainment has increased over time, more than 3 million Californians ages 25–64 have attended some college but never completed a degree (California Competes 2021). Community colleges must address the specific needs of adult learners, especially those potential graduates who stopped out. Enhanced financial aid packages, flexible course and transfer-pathway options, and continued online course offerings could widen access.

Finally, pre-pandemic and pandemic-induced enrollment drops vary widely across the state and across campuses, according to analysis of community college enrollment by Linden et al. (2022), as the timing and extent of COVID case rates, county ordinances, and economic effects differed greatly. Thus, efforts to strengthen enrollment will also require localized approaches that address the specific needs of the communities in which community colleges reside. While such efforts must consider broader economic factors, they must also take into account the demographic composition of prospective students that live in their neighboring communities.

Enhance Programs Aimed at Improving Persistence and Course Success

Pre-pandemic initiatives and reforms—including AB 705, Guided Pathways, and Associate Degree for Transfer—were starting to change the structures that had long prevented students from accessing critical courses, pathways, and supports necessary to complete community college and to transfer. Though the implementation of reforms remained relatively effective amid the pandemic, reforms did not address all of its heightened challenges. Furthermore, our interviews with department chairs and faculty revealed that initiatives to enhance learning environments—such as implementing corequisite courses, embedded tutors, and curricular changes—were delayed or scrapped. Re-engaging and improving such initiatives will be crucial for ensuring that transfer pathways are accessible and fully resourced to meet the growing needs of students.

At the same time, expanded holistic and non-academic supports, in the form of mental health counseling and economic resources, are necessary to ensure that students do not fall off of the transfer pathway due to external obstacles. Colleges must strengthen and expand the availability of online supports and services so that they are available outside traditional business hours. Many colleges pivoted in this direction when the pandemic struck. Some provided online orientations, others stepped up counseling and tutoring, and many began to offer mental health services. Moreover, early alert systems and strong communication and collaboration between staff, faculty, and administration could be key to identifying and supporting students with higher risks of failing and dropping out. Outreach and communication with current students also must be expanded so that students are made aware of the resources available to them on and off campus.

Lastly, system- and college-wide efforts to improve persistence and course success must be embedded with equity-minded policies and reforms. Faculty, department chairs, and administrators shared that strong leadership and support, at the department and college level, and expanded opportunities for faculty training on equity ensure that staff are supported and fully resourced to address diverse student needs. Many faculty, especially during the pandemic, have increasingly embraced new classroom practices, pedagogy, and grading practices in an effort to elevate student voices and ensure equitable opportunities for success. Moving forward, this work should entail using data and research to assess the effectiveness of new initiatives and practices, and making necessary refinements to ensure they are producing the intended outcomes and effectively narrowing equity gaps.

Widen Access to Transfer Pathways to Retain Pre-pandemic Progress

Despite gains among students who remained enrolled during the pandemic, transfer progress and attainment continued to vary widely across student groups. Colleges must expand outreach and student supports as well as provide institutional coordination among counselors, faculty, and staff. Furthermore, reform efforts to improve access to and completion of transfer-level courses in English and math will be necessary to improve student outcomes, especially among underrepresented groups. Building on the strengths of learning communities, like Umoja and Puente, which aim to increase transfer rates for underrepresented students by providing culturally sustaining support services may be central to these efforts. In fact, several of the faculty members we interviewed worried that the limited reach of such programs may be restricting access to essential resources and services for students unable to join them.

More broadly, increased systemwide efforts to improve access by expanding the Associate Degree for Transfer (ADT) and collaborating with the UC and CSU systems will be critical to increase the volume and rate of community college transfers in California. Recent legislation, including AB 928 and AB 1111, both signed by Governor Newsom in 2021, are steps in the right direction. Together, both initiatives provide a critical foundation, addressing historical barriers to entry that have disproportionately limited access to transfer pathways for all students, especially those from underrepresented groups.

Adapt Course Offerings to Meet Student Needs and Demand

Looking ahead, colleges must evaluate how they can improve future course offerings to meet the changing demands and needs of incoming prospective students. Surveys conducted with community college districts and prospective students suggest that the demand for online and hybrid courses is increasing, with students citing the benefits of increased flexibility, convenience, and independence (CCCCO 2022). Such flexibility may be required to bring back students who chose not to enroll during the pandemic and instead prioritized work (Bauer et al. 2021).

At the same time, a survey of community college students enrolled in spring and summer 2020 found that more than three in four students were concerned about taking online classes in the fall (CSAC 2020). Currently, colleges have responded in different ways to these changes in demand and their unique pandemic experiences, with some colleges retaining a large amount of their online offerings and others transitioning to a mostly in-person environment.

As colleges continue to adapt, they must learn from their pre-pandemic and pandemic experiences to ensure that the quality of in-person and online courses is improving and they are providing students and instructors with the necessary resources and opportunities to succeed. Continued research and reforms are essential to ensure that courses and supports that remain online, or transition back to in-person formats, are high quality and do not produce or widen inequities in student outcomes.

Expand Institutional Research and Establish a Longitudinal Student Database

The effects of the pandemic on community college students are only beginning to emerge. More research is needed at the system and college level to identify students who are less likely to enroll or persist in future terms, who need additional academic and basic needs supports, who would benefit from expanded access to counseling and tutoring services, and who require increased flexibility in course offerings.

At the same time, external research is needed to further inform policy and recovery efforts at a broader scale. A longitudinal data system would allow researchers to inform efforts to help ensure equitable access, success, and transfer progress, better track students’ outcomes in college and beyond, and identify successful programs and initiatives that serve historically underrepresented students more effectively. The California legislature and the governor support establishing a longitudinal database and efforts are already underway to establish a data system that connects K–12, higher education, workforce, and social services data (Jackson 2021).

Topics

Access Completion COVID-19 Equity Higher EducationLearn More

Improving Regional Representation among Community College Transfers

Testimony: Enrollment Declines in California Community Colleges