Table of Contents

- Introduction

- College is a good investment

- College graduates get higher-quality jobs

- College graduates fare better during recessions

- Still, college is more expensive than ever

- But most students don’t pay the sticker price

- Public college students have less debt

- Public and nonprofit colleges are a better financial bet

- Finishing a degree is important

- Majors matter for future earnings

- Wage inequities persist

- Society benefits from higher education

- More students need a chance at college

- Additional figure notes

We explore whether the benefits of a college degree outweigh the costs.

Although most California parents want their children to graduate from college with at least a bachelor’s degree, roughly three-quarters worry about being able to afford a college education. Sticker shock and an understandable reluctance to take on debt lead many students and parents alike to wonder if college will actually yield higher earnings, better jobs, and a brighter future down the road.

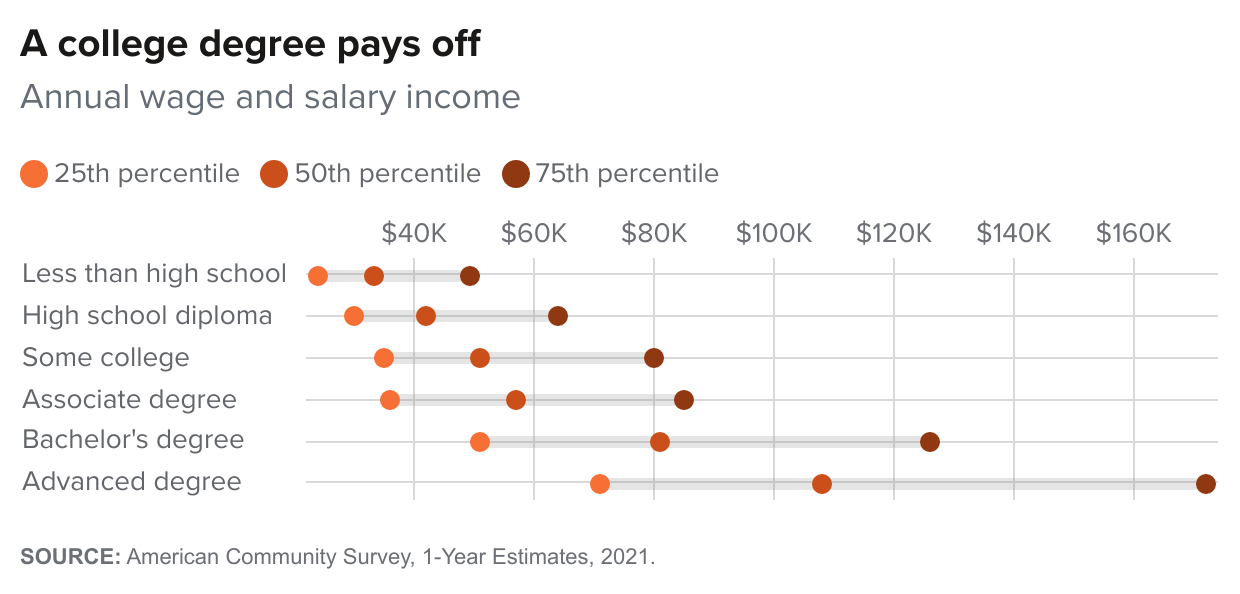

College is a good investment

Today’s labor market increasingly rewards highly educated workers: In 1990, a worker with a bachelor’s degree earned 39 percent more than one whose highest level of education was a high school diploma. By 2021, the difference had grown to 62 percent (and closer to 90% for workers with graduate degrees).

Currently, California workers with a bachelor’s degree earn a median annual wage of $81,000. In contrast, only 6 percent of workers with less than a high school diploma earn that much (12% of those with at most a high school diploma). Over time, the higher incomes of college graduates accumulate into much higher levels of wealth, with graduates having more than three times as much wealth as households with less-educated adults.

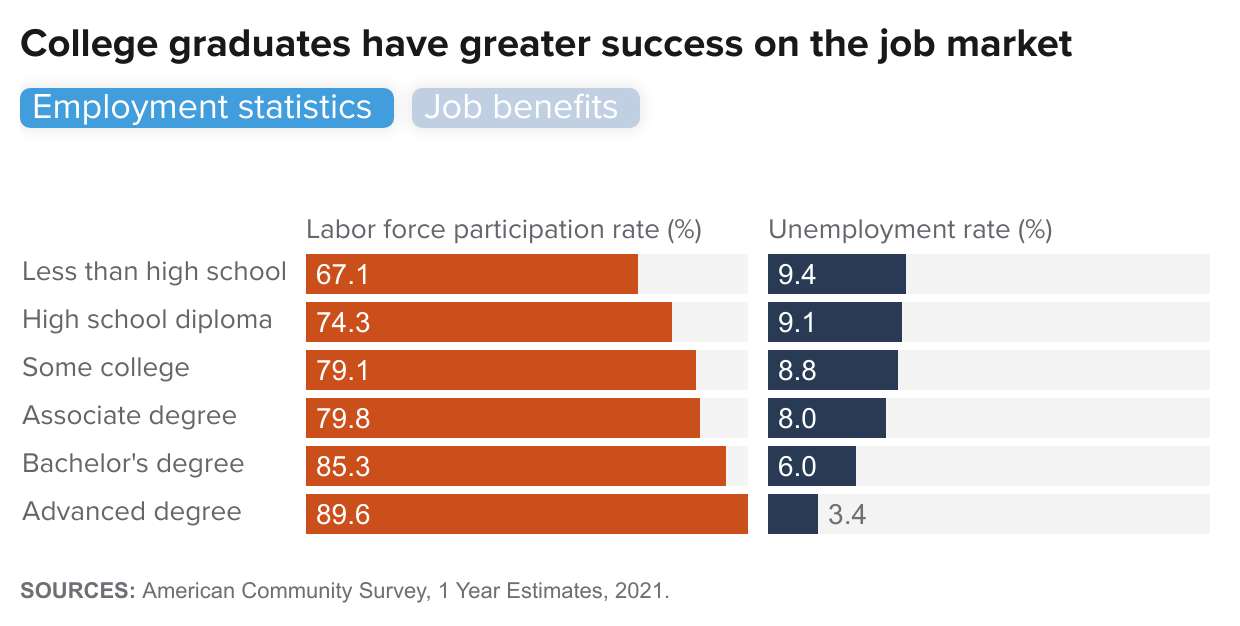

College graduates get higher-quality jobs

Beyond wage gains, the job market favors college graduates in other ways as well. Graduates are more likely to participate in the labor force, less likely to be unemployed, and more likely to have full-time jobs. Among full-time workers, college graduates are more likely to have jobs that offer paid vacation, health insurance, retirement, and flexible work arrangements. These forms of non-wage compensation help provide greater financial stability and security over the long run.

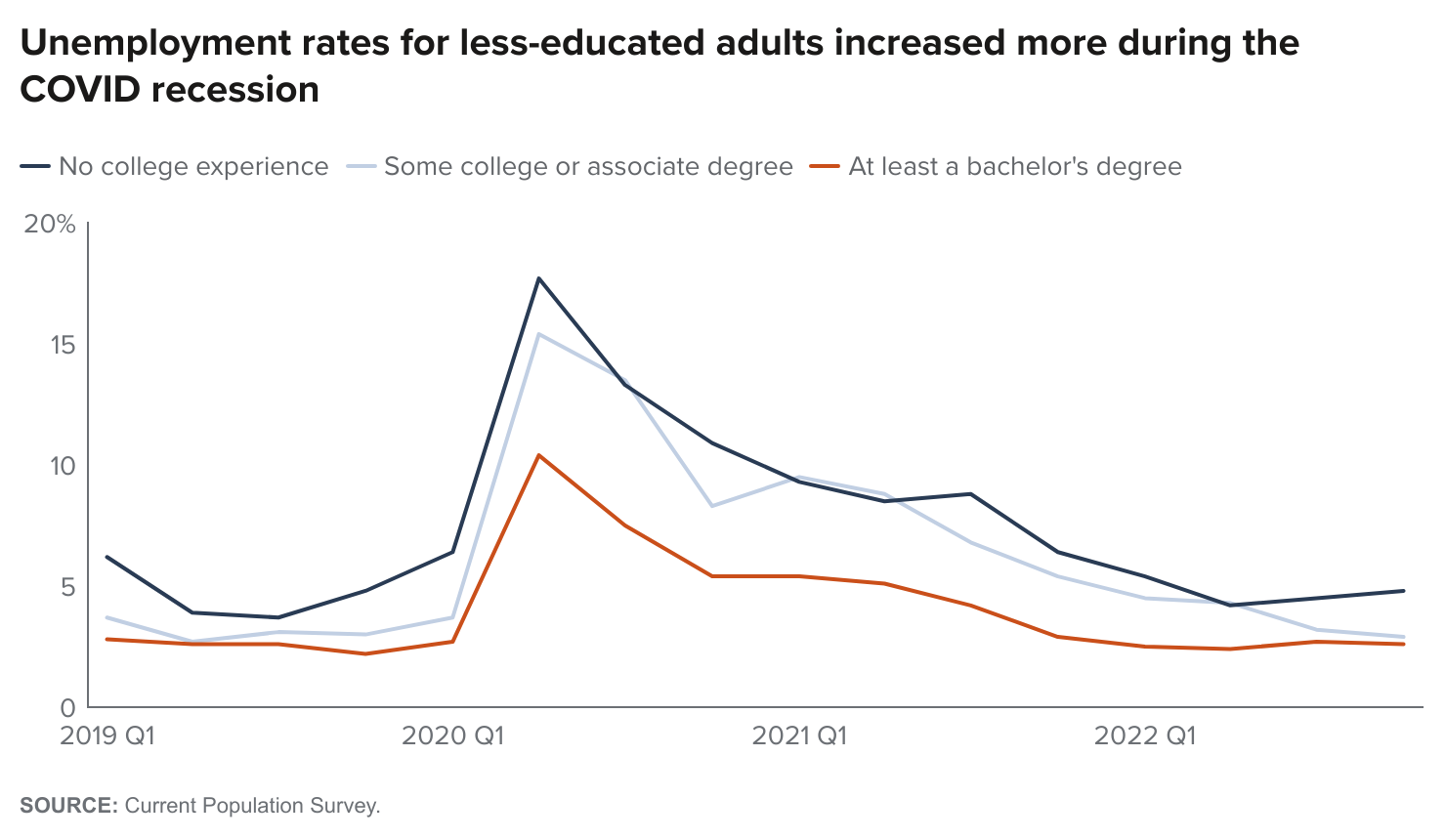

College graduates fare better during recessions

College graduates not only earn higher wages and have higher-quality jobs, but they are also better protected during economic downturns. In the past several recessions, less-educated workers have borne the brunt of employment losses. During the worst of the COVID-19 recession, the unemployment rate for those with no college experience was 18 percent, compared to 10 percent for those with a bachelor’s degree.

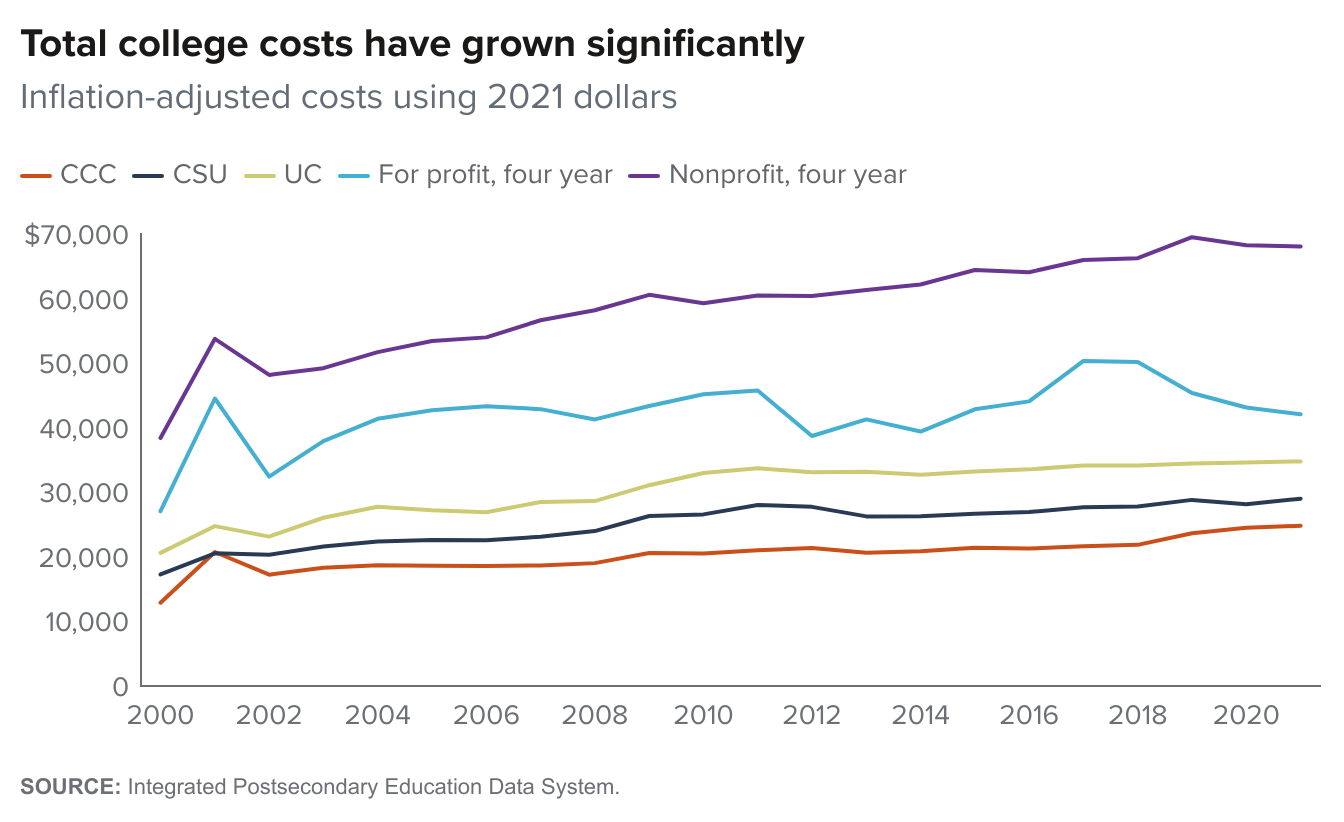

Still, college is more expensive than ever

Students who want to reap the benefits of college face rising costs, which have increased between 50 and 100 percent across different types of colleges since 2000. In 2021, a nonprofit private college in California cost an annual average of $68,000 for undergraduates, including tuition, room and board, books, and other fees. Public colleges are far less expensive but prices have still gone up for in-state undergraduates—reaching nearly $35,000 per year at the University of California (UC), $29,000 at California State University (CSU), and $25,000 at the California Community Colleges (CCC).

Housing—not tuition—is the key driver of rising costs at public colleges. For example, among CSU students, housing accounted for 56 percent of the overall cost of attendance in 2021 (tuition accounted for 26%). After adjusting for inflation, public college tuition is actually lower now than it was a decade ago, thanks to increases in state funding.

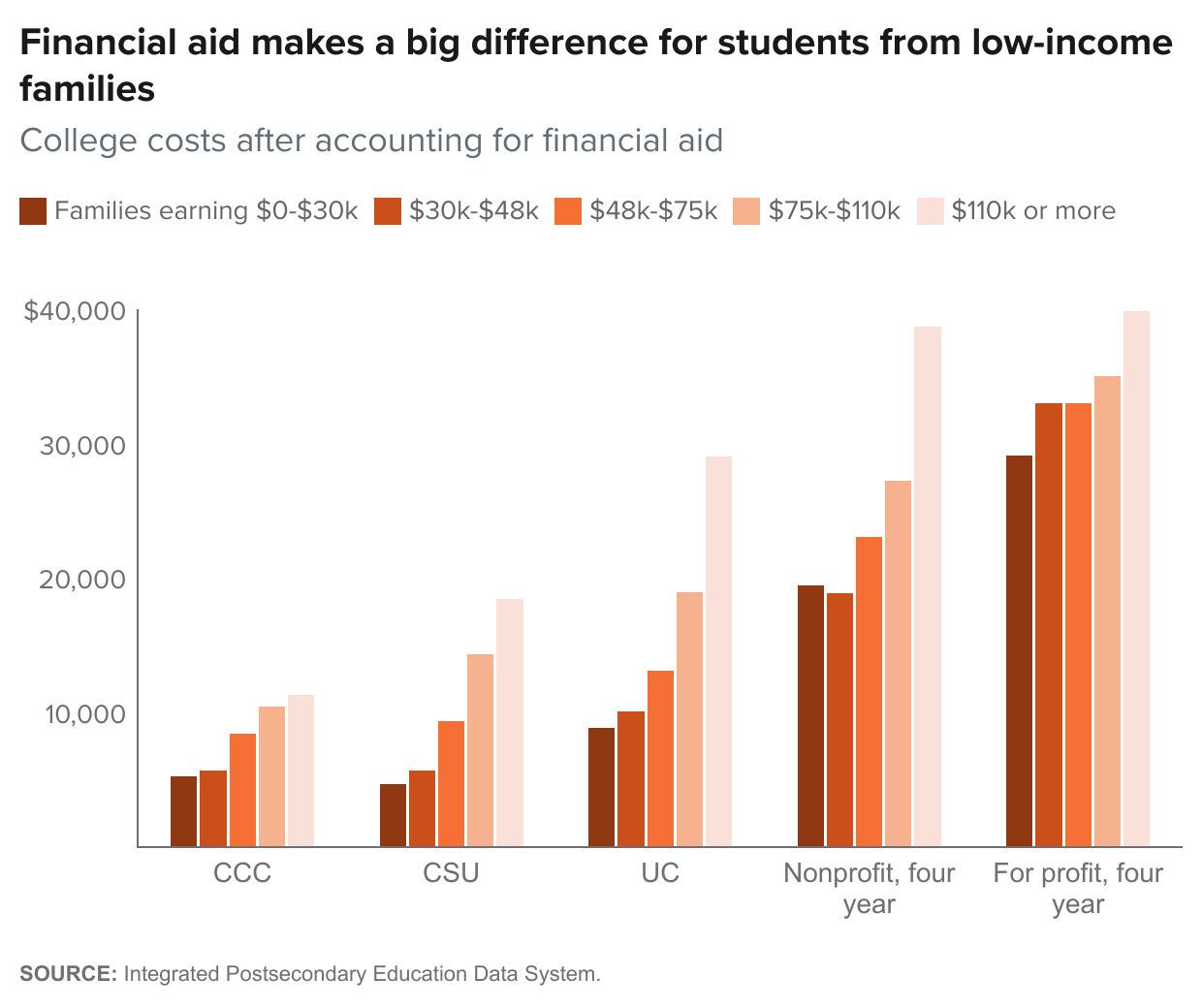

But most students don’t pay the sticker price

Financial aid can reduce costs tremendously, especially for students from low-income families. A CSU student whose family earns less than $30,000 pays $4,700, on average, in annual college costs, compared to over $18,000 for a student whose family income exceeds $110,000. Unfortunately, financial aid is underused: only about half of California high school seniors apply for aid, leaving an estimated $560 million in annual federal grants on the table. A new state policy will require more high school graduates to apply for financial aid, which could improve college access.

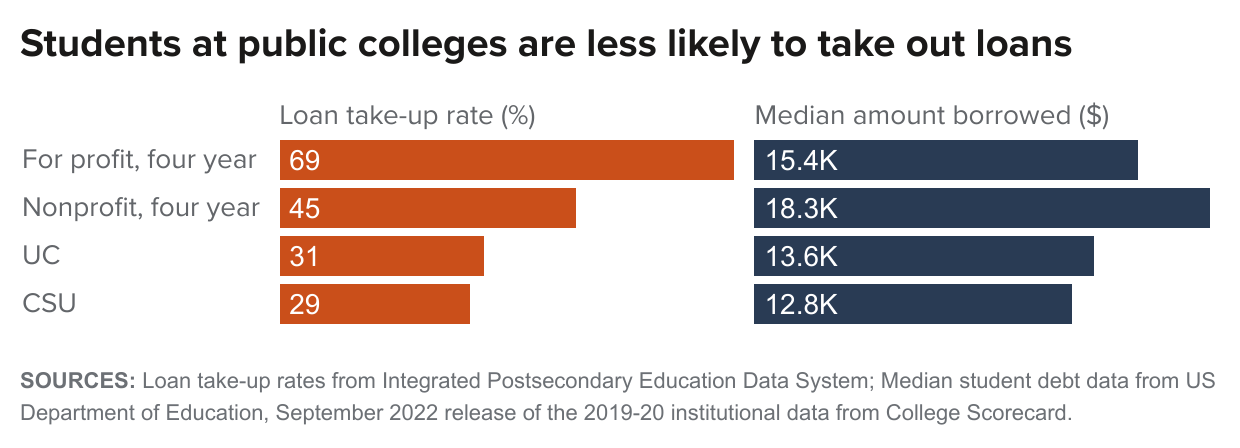

Public college students have less debt

An estimated 47 percent of California graduates from public and private nonprofit colleges have student debt (lower than the national rate of 62%). Overall, public college students are less likely to take out federal, institutional, or private loans. About three in ten CSU and UC students took out such loans in 2019. In contrast, 45 percent of students at nonprofit private colleges take out loans, and nearly seven in ten students at for-profit colleges do so. Federal loan amounts are also smaller at public colleges.

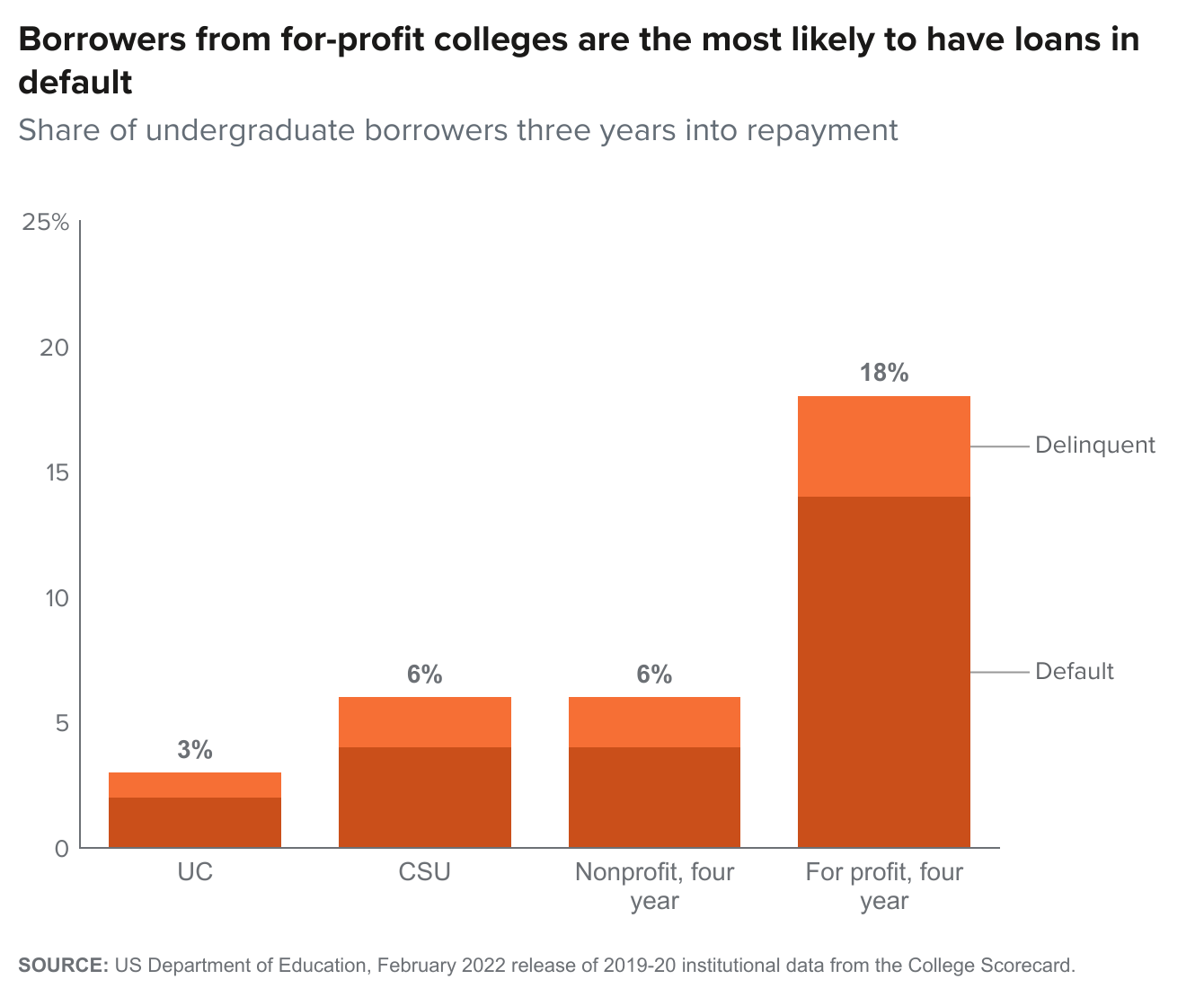

Public and nonprofit colleges are a better financial bet

Students from for-profit colleges struggle the most paying back their loans. Most students at for-profit colleges—disproportionately Black and Latino students—never graduate, and even for those who do wages are lower than for graduates from other colleges. Three years after college, 18 percent of borrowers from for-profit colleges have loans that are delinquent or have defaulted due to lack of repayment, compared with 3 to 6 percent of borrowers at public and nonprofit colleges. These statuses can damage credit scores, leading to higher interest rates and severely limiting access to mortgages and car loans.

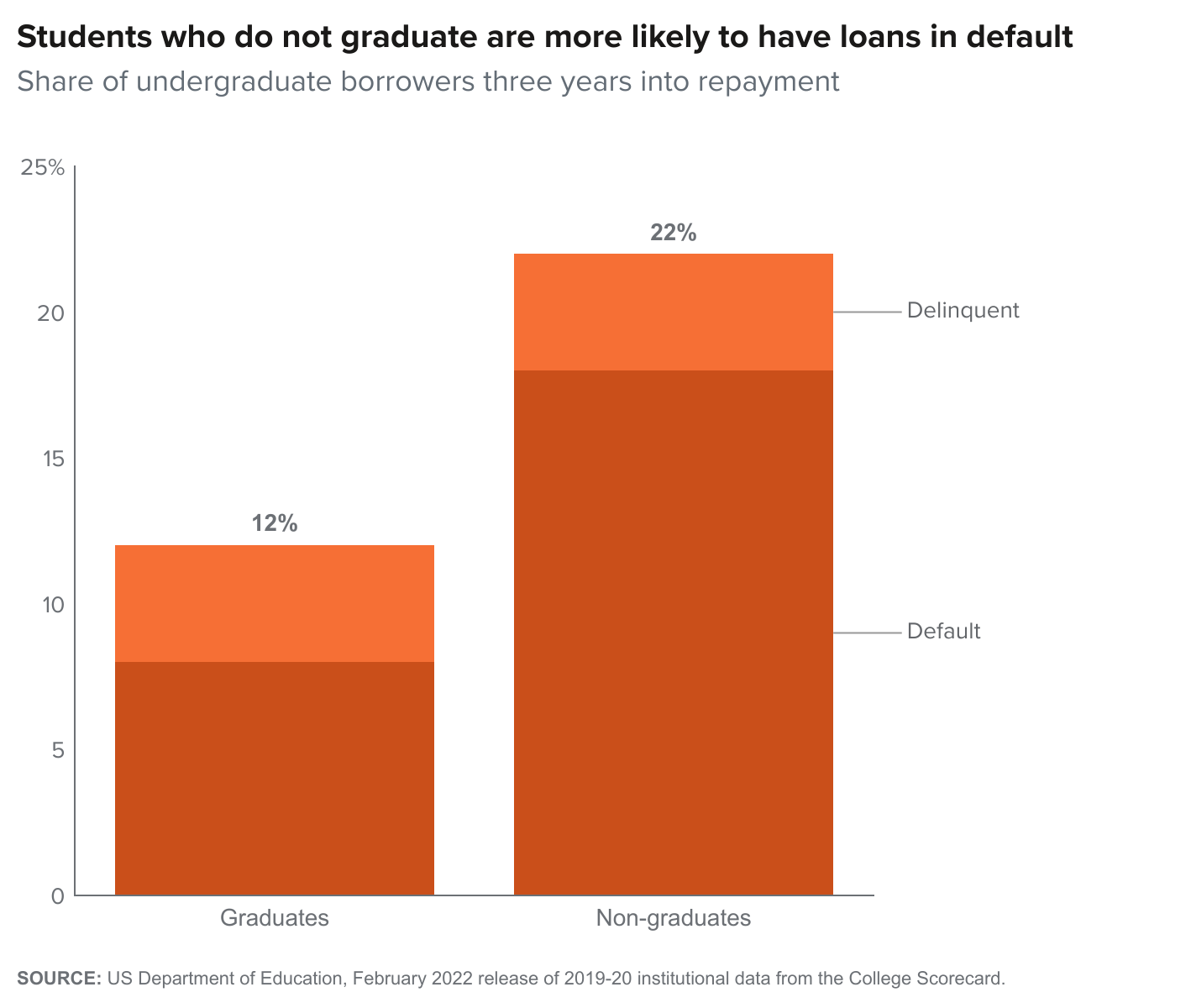

Finishing a degree is important

Students who never finish their degree do not see the same wage bump as degree-holders. This financial loss is compounded for those who took out loans to attend college in the first place. Three years after college, 22 percent of non-graduates have loans that are in default or delinquent, compared to 12 percent of graduates. Earning a degree in a timely manner is also important, as those who take longer than four years to complete their degree face extra schooling costs, run the risk of losing financial aid eligibility, and further delay their entry into the workforce.

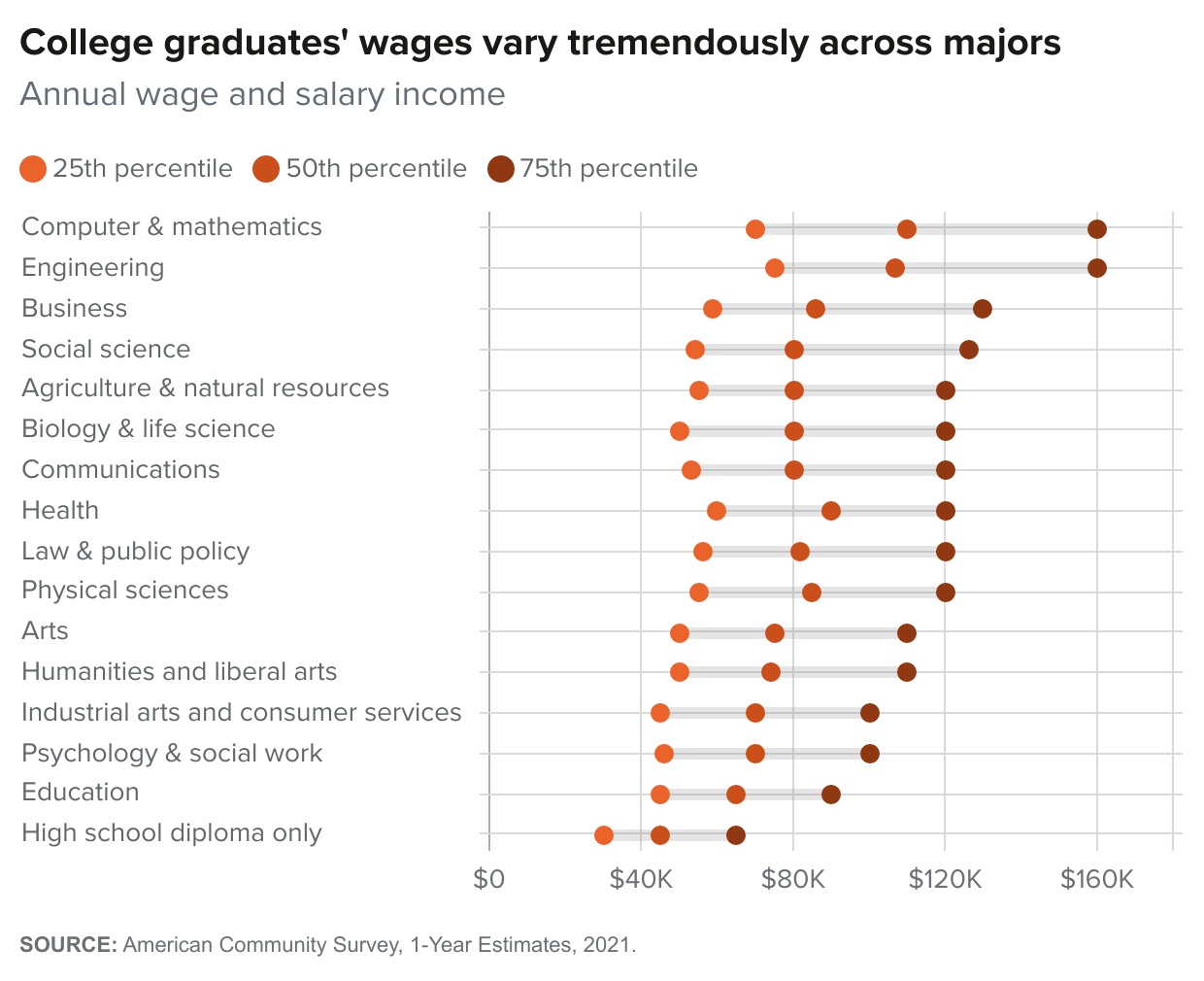

Majors matter for future earnings

The wage benefits of a college degree differ considerably across majors. Graduates in computer science and mathematics earn a median wage of $110,000 annually, almost double what graduates in education make ($65,000). There is also a great deal of variation within majors: the top-earning graduates in health make $120,000 annually (75th percentile), twice as much as the lowest-earning graduates in health ($60,000 for the 25th percentile). Nevertheless, even lower-earning college graduates tend to make more than workers whose highest level of education is a high school diploma.

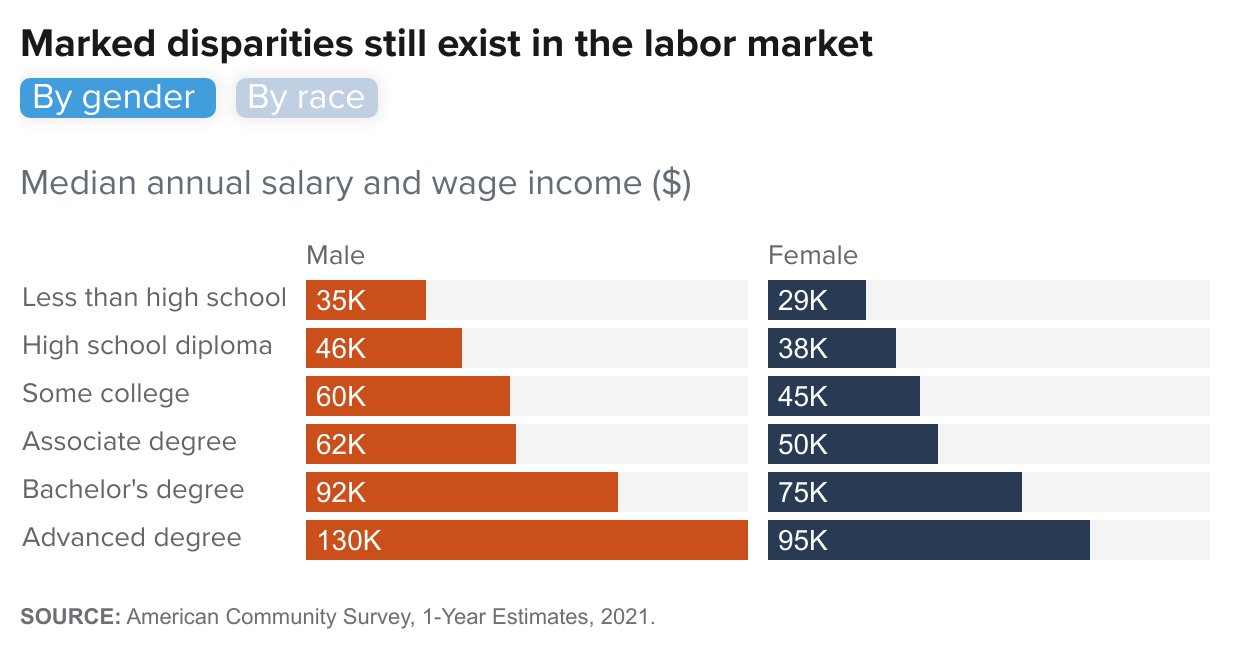

Wage inequities persist

Although workers across gender and racial/ethnic groups see a wage premium for earning a college degree, marked disparities still exist in the labor market. For male workers with a bachelor’s degree, the median annual wage is $92,000, compared with $75,000 for college-educated female workers. Similarly, white workers make more than Black and Latino workers across all levels of educational attainment. Several factors contribute to these gender and racial pay gaps, including labor market discrimination and years of work experience. Further, the underrepresentation of female, Black, and Latino students in the most financially rewarding programs of study, such as computer science and engineering, affects later job prospects, occupations, and earning potential.

Society benefits from higher education

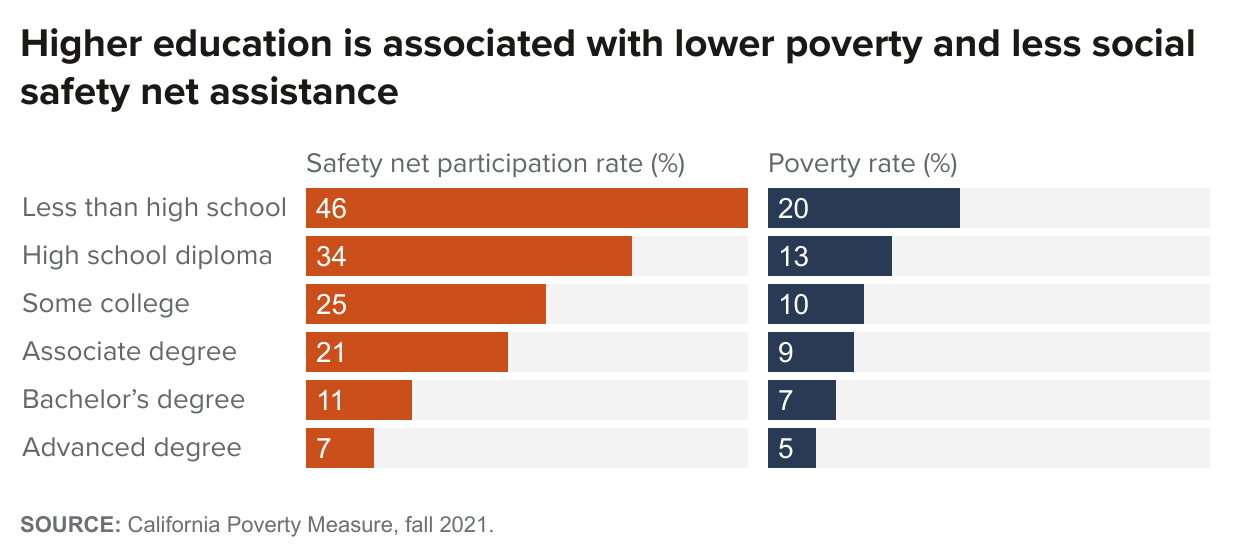

Higher education is a critical driver of economic progress. It is also the key policy lever for improving mobility from one generation to the next, especially for low-income, first-generation, Black, and Latino students. As the state’s economy has evolved, the job market has increasingly demanded more highly educated workers, a trend that is projected to continue into the future.

In addition to having higher earnings and better job benefits, college graduates are more likely to own a home and less likely to be in poverty or need social services. Society as a whole is also better off, thanks to lower unemployment, less demand for public assistance programs, lower incarceration rates, higher tax revenue, and greater civic engagement.

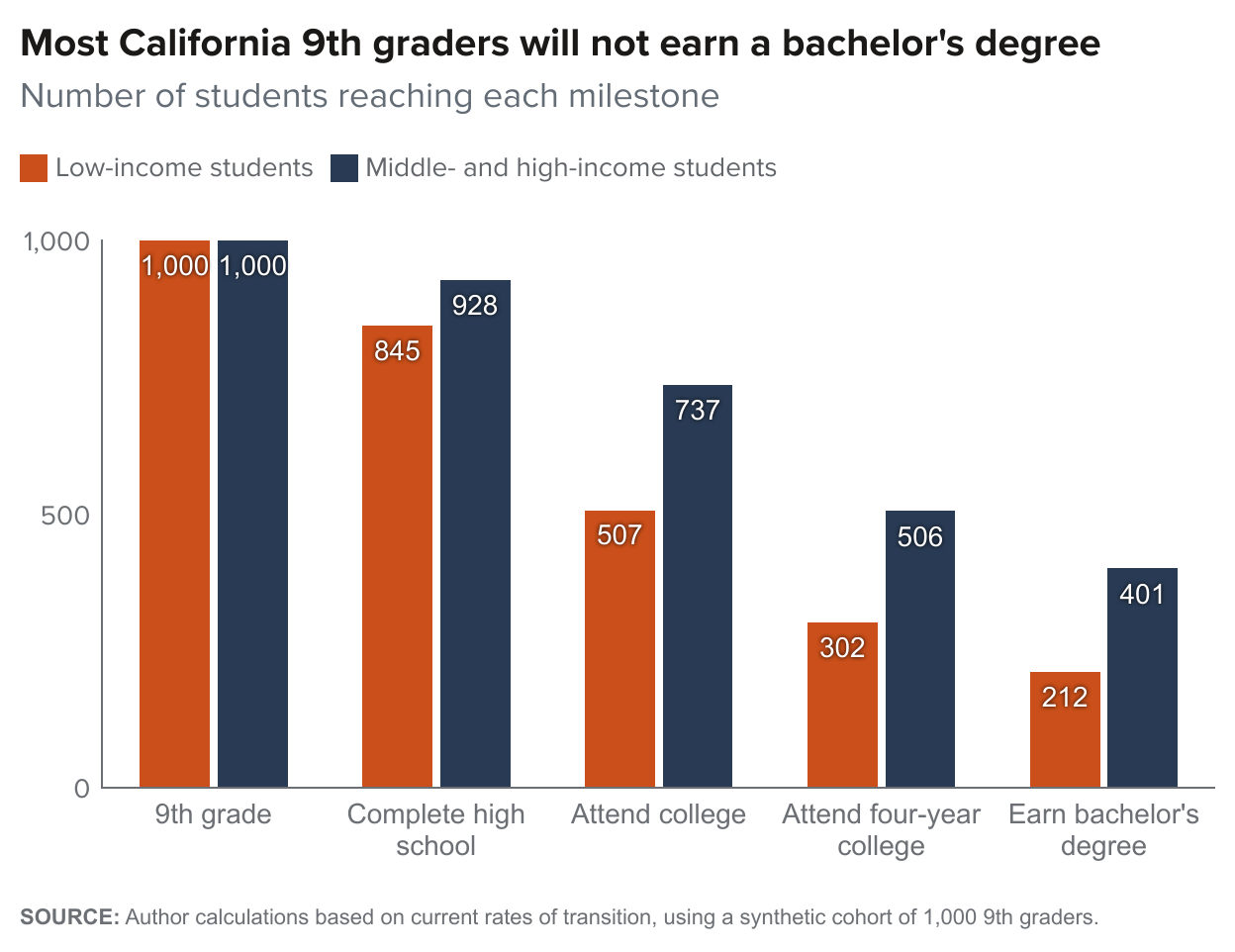

More students need a chance at college

While a college degree does not guarantee financial security, for most students it represents their best chance of achieving economic prosperity. Although the state has made enormous progress, more work is needed to improve student success at key transition points, including high school graduation, college enrollment, transfer, and college completion. If current enrollment and completion rates continue, most California 9th graders will not earn a bachelor’s degree. And at every step along the way, low-income students—who account for more than half of the state’s public K–12 students—are less likely than their higher-income peers to make it to and through college. Unfortunately, a similar story holds true for other underrepresented groups.

California and its higher education systems have already made tremendous strides in expanding access and improving completion so that more students can enjoy the benefits of a college degree. At the PPIC Higher Education Center, we are tracking the impact of these historic investments and policy changes, working to ensure that they have their intended effects, and advancing evidence-based solutions to further enhance educational opportunities for all California students.