Most California school districts offered summer learning programs in 2021 to help students regain educational ground after a protracted period of remote instruction. Summer school is historically oriented around credit recovery and improving course grades; during COVID-19, it offered more diverse programming, including learning acceleration, mental health and wellness services, and targeted interventions for English Learners and students with disabilities. There is some encouraging evidence that this programming has been benefiting children who need it the most.

As federal and state stimulus funding—such as Extended Learning Opportunity (ELO) grants—began flowing to districts in spring 2021, more than 80% of California school districts planned to use the funding for summer programming; 24% of California families reported that their children participated in summer learning programs. In San Diego Unified—California’s second-largest school district—more than one in four students signed up for the academic summer program, 12 times the usual level of participation.

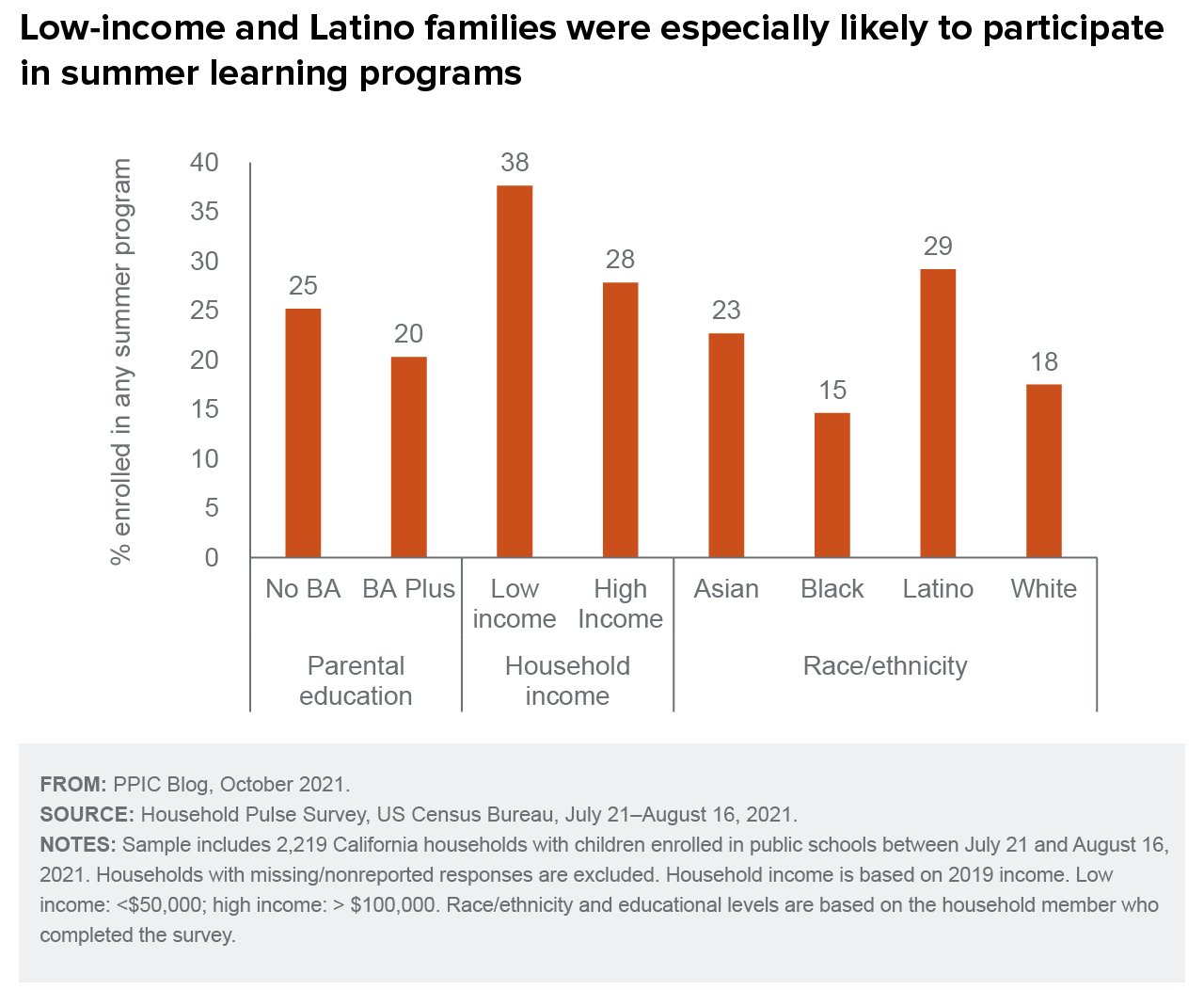

A significant portion of low-income students (38%) enrolled in a summer school program. These students struggled more during distance learning due to various factors, including lack of access to technology and reliable internet. Latino students enrolled at an above-average rate (29%), while enrollment among Black students was below average (15%).

The low Black student enrollment rate is surprising, given that a disproportionate share of Black students are low income and their learning trajectories were among those most disrupted. Reporting suggests the rise of the delta variant coupled with perceptions that some students performed better in a remote environment may have dissuaded parents from sending their children to in-person programs, and a survey of parents in Los Angeles Unified suggests these feelings were more prevalent among Black families.

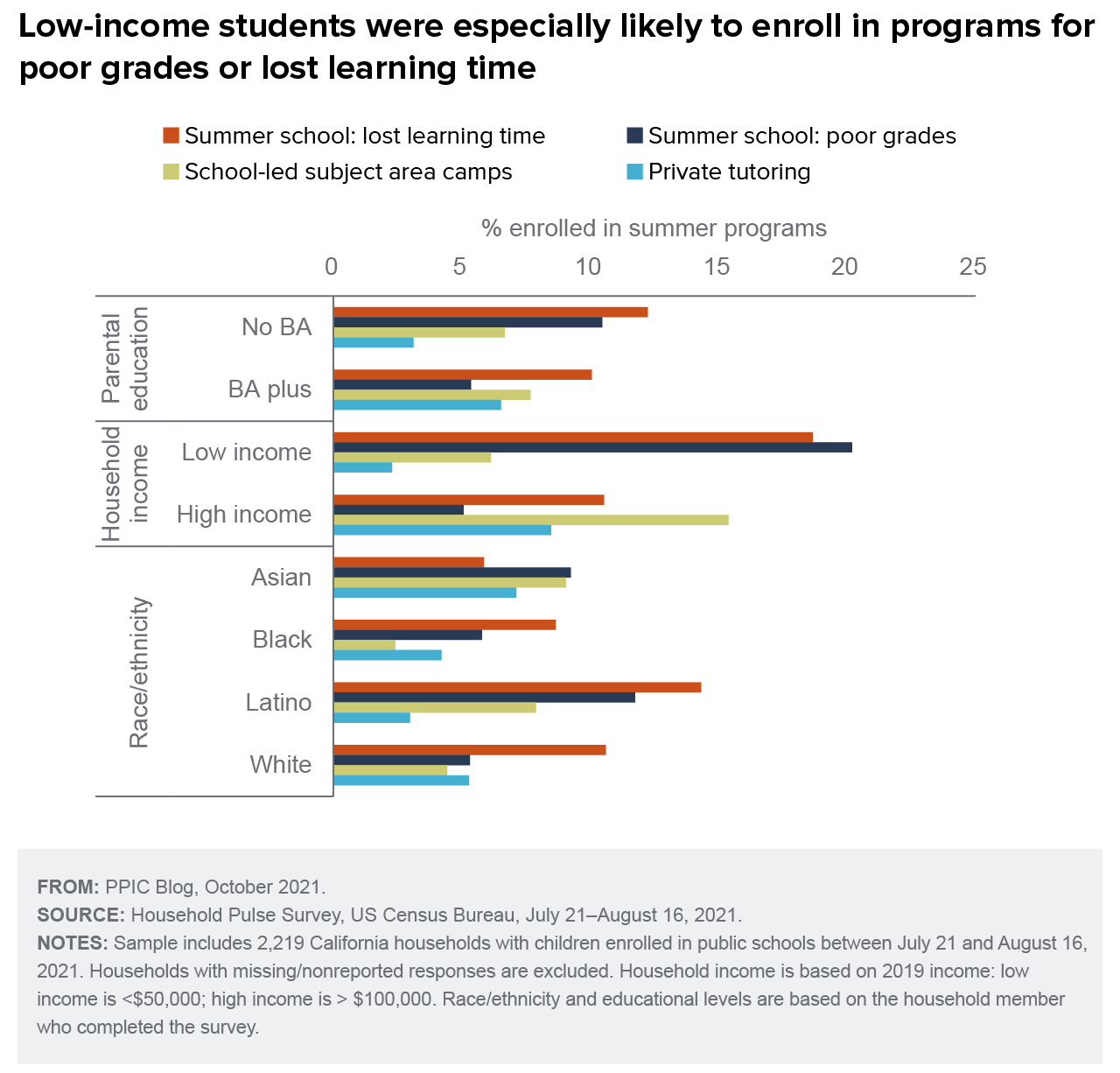

The most common type of summer learning was school-provided instruction to make up for lost learning time (12%), followed by making up for poor grades (9%), attending a school-based subject area camp (7%), and private tutoring (4%). The relatively high shares of low-income students attending summer school to address poor grades (20%) or make up for lost learning time (19%) suggests that districts effectively targeted their resources to students with the greatest need.

High-income students were especially likely to enroll in private tutoring and summer camps focused on a specific subject area. Among racial/ethnic groups, Asian students were most likely to enroll in school-led area camps and private tutoring. However, many Asian students enrolled in summer school to address poor grades.

Summer school may not be a panacea for the academic, social, and emotional turmoil of remote learning. However, it has given many students—particularly those most affected by the pandemic—an opportunity to re-engage in school and make up for lost learning time.