Early in the pandemic, state and county governments sought to curb coronavirus transmission among the incarcerated by instituting policies that quickly reduced jail populations. A few months later, jail populations rebounded and then stabilized as COVID-19 spread across the state in successive waves. Even though jails are over capacity in just two counties, more than 15,000 people are housed in overcrowded jail conditions associated with virus proliferation.

Last spring, California’s state and local governments acted swiftly to prevent COVID-19 from spreading through county jails and communities. Weeks after the governor’s emergency declaration, the Judicial Council set bail at $0 for misdemeanors and low-level felonies; most law enforcement agencies reduced their booking rates; county courts were shuttered; and some people secured early release from jail.

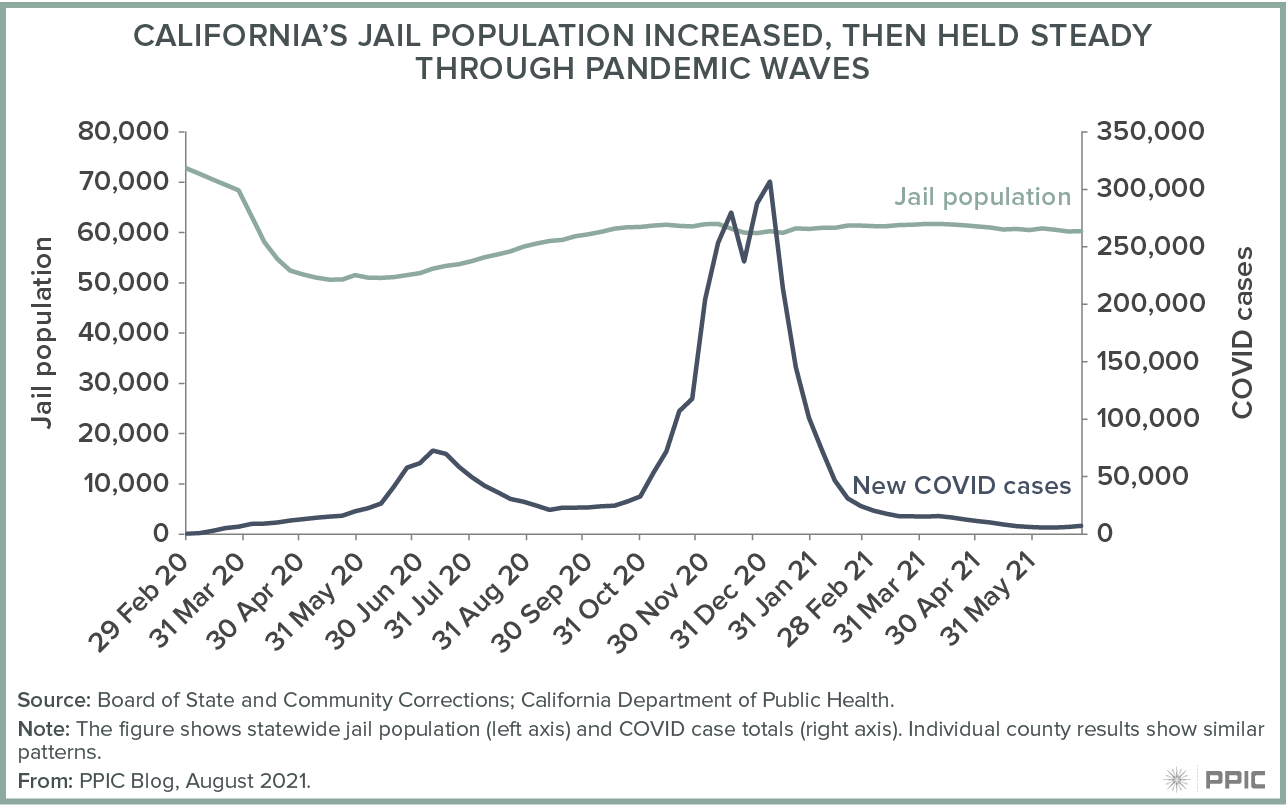

These policies rapidly reduced the number of people awaiting trial and serving sentences in county jails. Within two months, the statewide jail population fell from more than 72,000 inmates in February to just above 50,000 in May 2020. During that period, weekly bookings were halved relative to their pre-pandemic level of about 17,000.

As coronavirus cases ebbed and flowed across the state, jails were identified as potential sites of community spread and drivers of racial disparities in infection rates. Yet the statewide jail population began to climb as monthly aggregate community infections reached 20,000 in July 2020. By October, California jails held 61,000 people. The jail population stabilized near that level, even as the state reported more than 300,000 new cases in January 2021.

It is difficult to ascertain whether maintaining this level of incarceration affected those living and working in California jails. Of the 53 counties that ever reported data to the Board of State and Community Corrections (BSCC), 48 registered COVID-19 infections in jails; 22 reported at least one hospitalization, and 6 reported at least one death. These are probably undercounts, because not all counties reported data consistently, testing was sporadic, and post-release hospitalizations and deaths were not tracked.

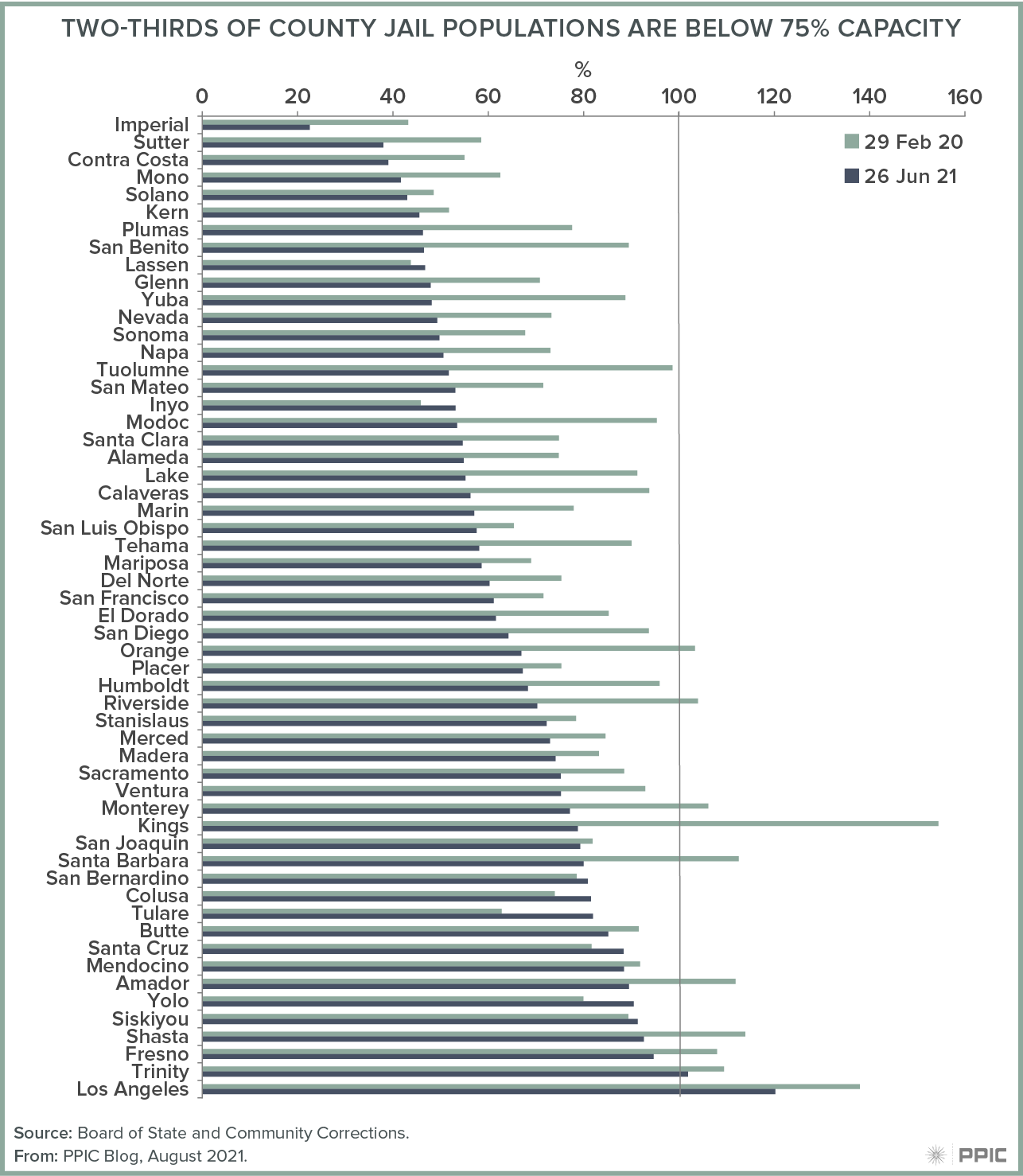

Although jail population levels do not seem to have shifted in response to successive COVID-19 waves, there were 11,000 fewer people in jail at the end of June than before the pandemic. Jail populations are below their pre-pandemic levels in all but seven counties.

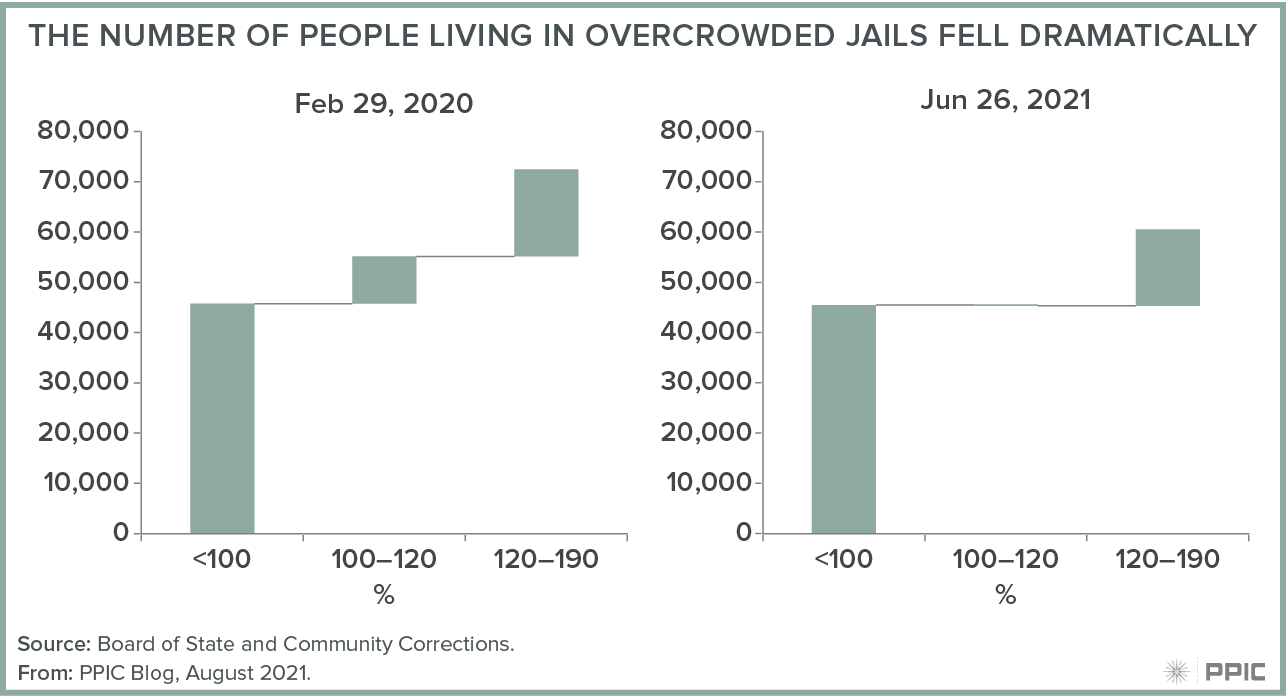

Likewise, only two county jail populations are currently over capacity, compared to ten before the pandemic. As a result, fewer inmates live in overcrowded conditions. Before the pandemic, nearly 27,000 jail inmates lived in overcrowded facilities. At the end of June, 15,000 people lived in crowded jails, mainly in Los Angeles County.

As California weathers a third COVID-19 wave driven by the delta variant, state and local governments need more robust systems in place to gather and track information about infections in jails. Testing could be more systematic and transparent, as it is in state prisons, to enable adjustment of jail populations to balance shifting public safety and public health needs.