Key Takeaways

To make voting safer during the pandemic, California implemented a number of reforms for the 2020 general election, including mailing every voter a ballot and consolidating in-person voting options in exchange for more early voting alternatives. To inform election administration for an eventual post-pandemic world, we examine how these changes affected the representativeness of the electorate, especially gaps in voter turnout between young people and seniors and between non-Hispanic white people and people of color.

- Mailing every voter a ballot almost always made the gap in turnout between overrepresented and underrepresented groups smaller; the effect was somewhat stronger for young people than for people of color, but it was evident across many groups. California’s turnout gaps consistently shrank in 2020, sometimes more so than in other states. →

- In Los Angeles County, mailed ballots raised turnout across groups in the March 2020 primary. But mailed ballots disproportionately elevated turnout for overrepresented groups, producing a larger turnout gap. This effect likely reflected certain features of primary elections more than problems with Los Angeles County in particular. →

- Consolidating polling places for in-person voting in the 2020 general election widened the turnout gap for African Americans and Latinos, and sometimes for Asian Americans and young people. Moreover, limiting in-person options actually discouraged turnout for African Americans, and often for Latinos. →

To achieve stronger equity in voter turnout, California policymakers should review the strategies around consolidating in-person options, including consolidations that appear in the package of changes under the Voter’s Choice Act of 2016.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic introduced the risk of viral transmission to in-person voting in the 2020 presidential election. Faced with this danger, many states changed election policies to facilitate voting by mail. California adopted universal vote-by-mail (VBM), where every active voter received a ballot in the mail by default.

To manage staffing challenges and reduce transmission risk, California also permitted counties to consolidate polling locations in prescribed ways. This left many counties with fewer in-person voting options but with more choices before Election Day in the form of unstaffed drop boxes and early voting sites. California has since passed AB 37, which commits the state to universal VBM without making a decision about in-person options.

These changes all came on the heels of a decade of election reforms the state had adopted to expand turnout and make the electorate more representative. The reforms included an online option for voter registration, “pre-registration” for 16- and 17-year-olds, a more robust system for voter registration at the Department of Motor Vehicles, same-day voter registration, and a universal VBM system—the Voter’s Choice Act—adopted by certain counties.

The effects of the pandemic changes on voter turnout have been mixed. While universal VBM increased turnout, changes to in-person voting had smaller and sometimes contradictory effects (McGhee et al. 2021).

But it is not enough to consider only changes in total turnout. California has an “exclusive electorate”—a voting public that does not accurately represent the population of the state as a whole (Baldassare et al. 2019) due to a gap in who turns out to vote. That is, a gap exists between currently overrepresented groups, like seniors and white people, and underrepresented groups, like youth and people of color (Fraga 2018). Did changes to voting policies also affect this turnout gap?

California’s reforms to voting policies, while important and well-intentioned, may have disrupted certain voter habits. Communities of color and young people have traditionally voted in person at higher rates, and reducing in-person options asks more of voters who prefer such options: if they have a new voting location, they must become aware of the change and find the new location, which may also be farther from home than the old one. Adding a mail option and more early, in-person choices might not have been enough to compensate.

Communities of color and young people can also be harder to reach with information about election changes, in part because members of these groups are more likely to change addresses without getting updated in the registration file. Young people were especially likely to move around in 2020, often to move in with their parents as colleges and universities closed their doors to in-person instruction.

Moreover, the pandemic itself has been hard on communities of color in California, especially Latinos and African Americans, in ways that may have interacted with election access. By November 2020, Latinos were significantly overrepresented among COVID-19 cases (59%) and deaths (49%) compared to their share of the total population (39%); African Americans were not overrepresented among cases but were more likely to die from the disease (7% of deaths vs. 6% of total population) (Romero 2020). Such consequences made it especially important to avoid in-person voting, and likely turned attention toward personal matters in the midst of the election.

Election Policies Adopted for the Pandemic

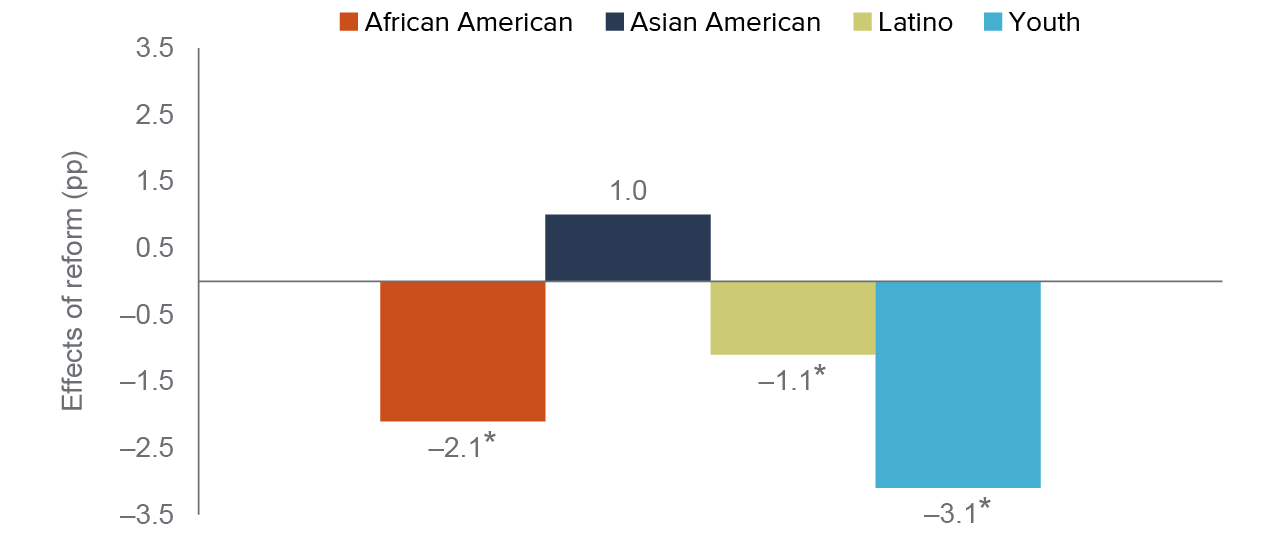

Before the pandemic, California already had one of the highest rates of vote-by-mail in the nation (57.8% in 2016). Nor was California the only state with universal VBM during the pandemic. Colorado, Oregon, Washington, and some counties in New Mexico and Utah had made the change by the 2016 election, and the rest of Utah, as well as Hawaii, New Jersey, Nevada, Vermont, the District of Columbia, and some counties in Montana and Nebraska had done so by 2020.

Many California counties even had some experience with a universal VBM approach. Three small rural counties—Alpine, Plumas, and Sierra—had eliminated virtually all in-person voting by 2016. An additional 15 counties—representing a little more than half the state’s registered voters—had held at least one universal VBM election under the state’s Voter’s Choice Act (VCA) by the fall of 2020. The VCA was a voting reform passed in 2016; counties that chose to adopt it switched to universal VBM and consolidated in-person voting locations in certain prescribed ways (see below).

Though all active California registrants received a ballot in the mail in the 2020 general election, the state gave counties some freedom to manage in-person voting. The counties adopting the VCA had already replaced the traditional polling place with a smaller number of larger, professionally staffed “vote centers” open to anyone in the county up to 10 days before Election Day. Voters in VCA counties could choose to mail in their ballots, drop them off at an unstaffed drop box, or take them to a vote center.

Every vote center was also connected electronically to the county voter registration list, so voters could go to a vote center to register to vote or cast a replacement ballot. In the 2020 general election, these VCA counties, plus the three that had removed virtually all in-person options, mostly continued with the approach they already had in place.

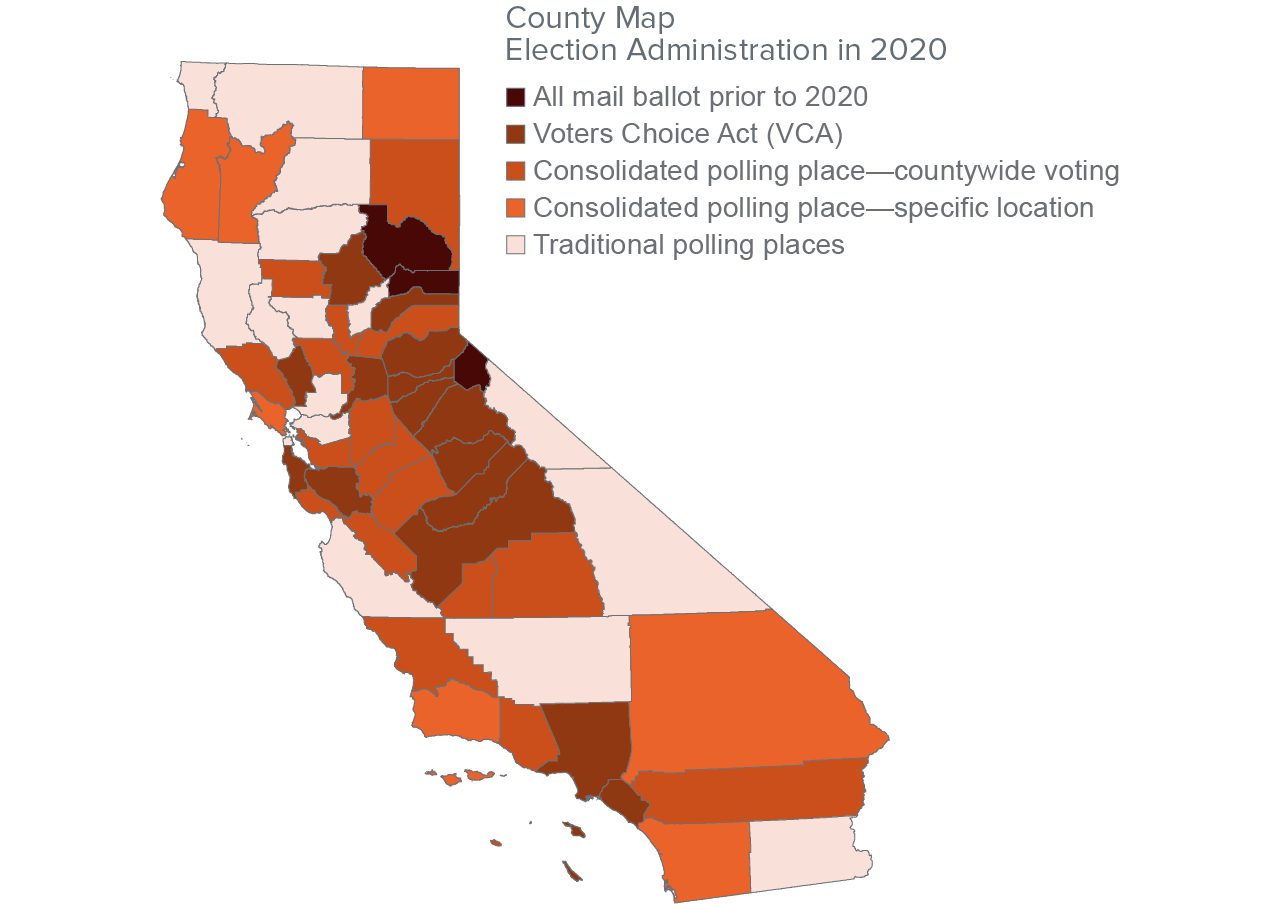

The remaining 40 counties chose one of three state-authorized approaches (see Figure 1):

- Sixteen counties continued with the traditional model: voters were assigned to a small neighborhood polling place, with the minimum number of polling locations dictated by existing election law.

- Seven counties consolidated into a smaller number of polling places serving larger geographic areas within the county, but with voters still assigned to a specific neighborhood site.

- Seventeen counties established voting locations that were open for at least four days and allowed any voter to use any location in the county. This approach was very close to the vote center model implemented for the VCA. However, the original VCA counties had more time to implement the reform, had to create a formal plan for the transition, and had been required to conduct more community outreach about the change.

California also required counties to implement a remote ballot system, whereby election officials emailed voters their ballot, and voters could mark it online, print it, and then return the ballot using one of the methods outlined above. This option—called remote accessible vote-by-mail (RAVBM)—was available to any voter upon request. Together these changes committed counties to providing some in-person voting options, but with more flexibility than would normally be the case.

Los Angeles was different from other counties

Los Angeles County deserves special discussion. It is by far the most populous county in the state, with one in four of the state’s registered voters. It is also home to a disproportionate share of the state’s voters of color, making what happens there especially relevant for turnout gaps.

LA County has had an unusually complex relationship with both mail voting in general and the VCA in particular. LA had the lowest VBM rate in the state before adopting the VCA—about 20 points below the statewide average. The county switched to the VCA in the March 2020 primary, but it received special permission to postpone mailing every voter a ballot. (This exemption itself had some exceptions, covered in greater detail below. And like the rest of the state, LA mailed a ballot to all voters in November 2020.)

In short, LA was home to an especially large in-person voting bloc composed disproportionately of voters of color who faced an unusually complicated transition to the VCA. Because these special circumstances deserve extra attention, we offer more analysis later in the report.

The experiences of VBM and in-person registrants

The decision to mail every voter a ballot erased any practical distinction between voters who had previously registered to permanently vote by mail (VBM registrants) and those who had said they wanted to vote at the polling place (in-person registrants). Both would now receive ballots in the mail and have the choice to return them to an in-person location, mail them in the postage-paid envelope, drop them off at a drop box, or vote a replacement ballot at an in-person location.

Yet in-person registrants did experience a bigger change to their accustomed method of voting. Some may not have heard they would receive a mail ballot, and in many counties, their normal polling place for in-person voting was significantly altered. By contrast, VBM registrants had already been receiving ballots through the mail for past elections and many were in the habit of returning them that way as well.

California’s counties took a range of approaches to in-person voting in 2020

SOURCES: California Secretary of State, November 3, 2020, General Election; Polling location and drop-off location statistics as of October 10, 2020.

NOTES: “All mail ballot” refers to three counties that had eliminated all in-person voting before the 2020 election. “Voter’s Choice Act” are the Voter’s Choice Act counties. “Consolidated polling place—countywide voting” refers to counties that moved to a smaller number of larger polling places according to the new legal guidelines, and made those consolidated locations available to any voter in the county. “Consolidated polling place—specific location” refers to counties that made the same consolidation but required voters to use a specific polling place in their community. “Traditional polling places” refers to counties that continued to follow existing legal requirements for in-person voting.

Other influences included new deadlines and automatic voter registration

California also made other important election administration changes in response to the COVID-19 threat. Before the pandemic, a mailed ballot had to be sent by Election Day and arrive by 3 days after; the state shifted this deadline out to 17 days after the election for the pandemic. The Secretary of State also implemented a statewide tracking system so voters could follow the progress of their ballot and verify it was counted.

Finally, 2020 marked the first presidential election under California’s automatic voter registration system. This system, which more assertively presses voter registration decisions on customers at the Department of Motor Vehicles, has greatly increased the number of registered voters and probably helped keep the records of existing voters up to date. While the state’s automatic voter registration law is not the primary focus of this report, it is the backdrop for the VBM changes that are, and we account for the reform in our analysis (see Technical Appendix B).

The Impact of Universal Vote-by-Mail

To understand how universal vote-by-mail affected turnout equity, we compare the states and counties that adopted the change to similar states and counties that did not. The pandemic made 2020 a highly unusual election year in many ways, including the many policy adjustments around the country to make voting safer and, of course, the direct effects of the pandemic itself on voter behavior.

To address these potential complications, we statistically account for turnout differences between counties and turnout change over time due to the COVID-19 caseload, automatic voter registration, the other mail ballot reforms adopted in 2020, and the variety of ways that 2020 was different on average for voters everywhere. We also highlight how California’s experience differs from the other states that adopted the change.

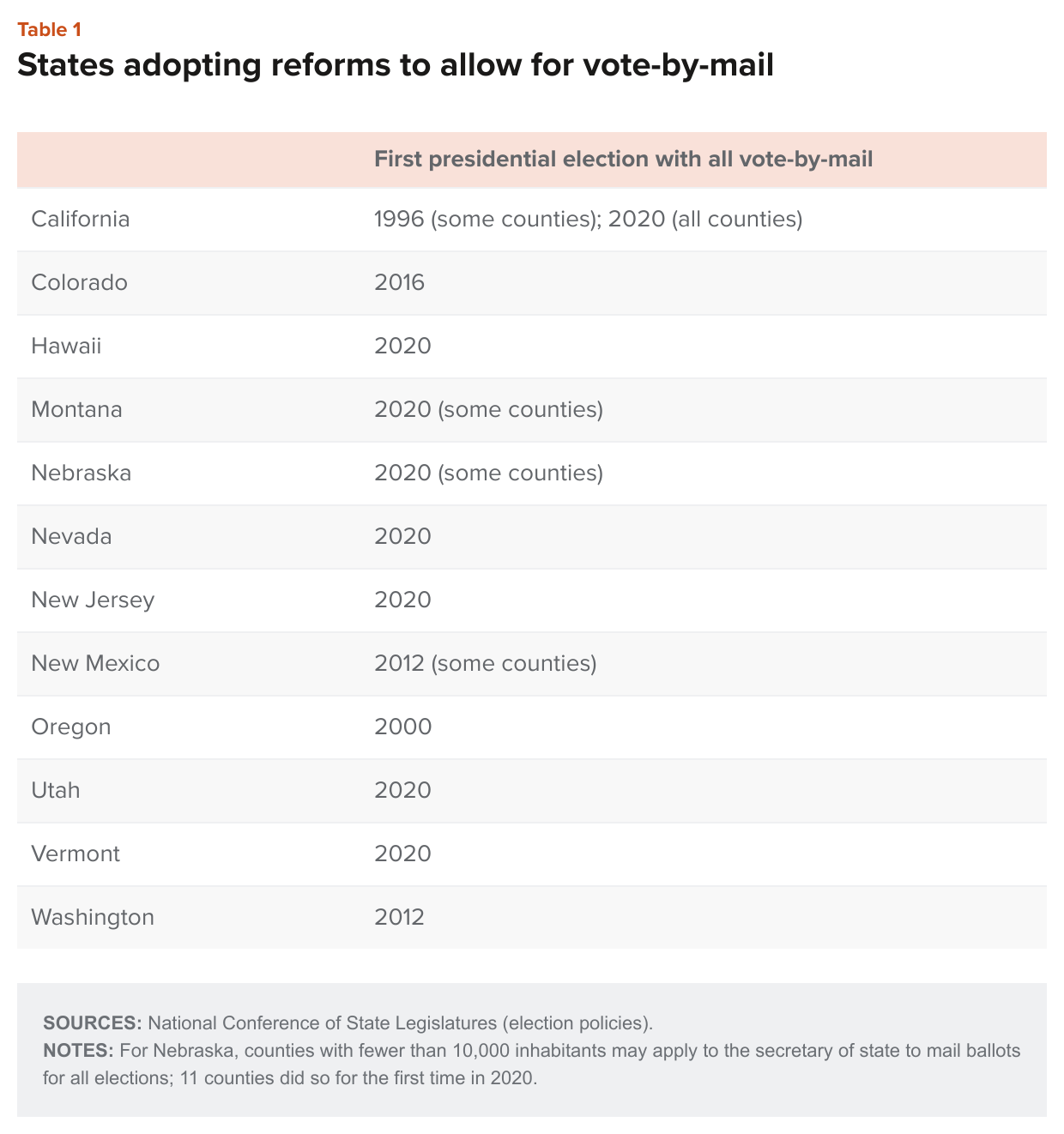

For many demographic groups in California, turnout equity improved under universal VBM. The Black-white turnout gap declined 3.0 percentage points, the Latino-white gap 2.9 points, the Asian American–white gap 1.8 points, and the youth-senior gap 3.2 points (Figure 2). The improved Black-white and youth-senior turnout gaps are particularly robust.

Universal VBM made little difference for African Americans outside California. Otherwise, the reform appeared to increase turnout for each demographic group by itself in addition to shrinking turnout gaps relative to non-Hispanic whites and seniors. Latinos (1.9 percentage points), Asian Americans (3.1 points), and young people (5.8 points) all made gains.

Because the results outside of California are the average of many different states, they come closer to an estimate of the effect of universal VBM itself. California’s specific experience might differ because it managed universal VBM especially well, because of the other changes it adopted, or for some other reason entirely. We offer the numbers only to give a sense of how well the state compared to the overall dynamics.

Voting equity in general elections has mostly improved under universal VBM

SOURCES: Catalist (registration and turnout data); Pew Research Center Non-Precinct Place Voting Study (election policies); National Conference of State Legislatures (election policies); Election Administration and Voting Survey (election policies); New York Times COVID-19 database.

NOTES: Turnout gap change across groups as measured by lagged dependent variable model described in Technical Appendix B. (*) statistically significant at two-tailed 95 percent confidence level.

The Special Case of Los Angeles County

The evidence in Figure 2 reflects broad patterns throughout the United States. More important, it shows the results for a general election, where turnout is usually high, as compared to a primary election, where turnout is lower. The effect of universal VBM might also be different on a more local level in an especially diverse area.

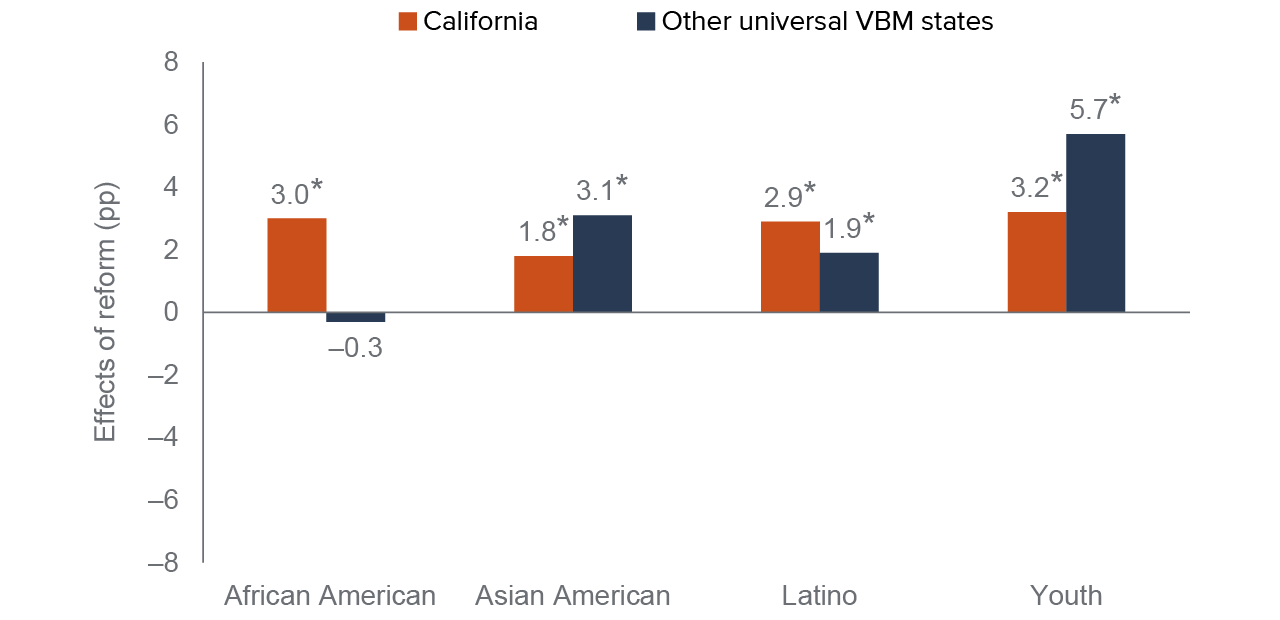

Los Angeles County used the VCA for the first time in the March 2020 primary. The VCA gave LA special permission to postpone mailing every voter a ballot and to focus only on consolidating polling places into vote centers. However, in state legislative and congressional districts shared with Orange County, LA was obligated to implement the full VCA—to send a ballot to every voter in addition to setting up vote centers. In those districts, even voters who did not request a ballot by mail would receive one, giving them the option to avoid in-person voting if they wanted. In the rest of LA County, however, voters would be required to vote at a vote center or request a ballot be mailed to them.

Figure 3 shows the difference between these two portions of LA for in-person registrants. (Details about the methodology behind these numbers are in Technical Appendix B). The turnout gap modestly improved for Asian American voters (1.0 percentage points), but worsened for young voters (–3.1 points) and for Latino (–1.1 points) and African American (–2.1 points) voters. Universal VBM did not appear to discourage any underrepresented groups from voting. In fact, it elevated turnout for all groups. But it elevated turnout more for seniors and non-Hispanic white people than for young people or people of color. The result was an even less representative electorate.

LA County’s March 2020 results suggest another perspective on the equity of universal VBM. When we examined the county’s turnout gaps in the context of national results in the 2020 general election, they were no worse than those of other universal VBM counties, which suggests the problem is not specific to LA County itself.

Instead, these LA County results likely differ because they come from a primary election. Overall turnout in primary elections is much lower than in generals. The same voters on the fence about participation in a primary will be highly likely to vote in a general, and so more likely to come from overrepresented groups (Arceneaux and Nickerson 2009). Thus, a neutral effect that nudges all groups toward participation may paradoxically push more overrepresented groups across the threshold in a primary than in a general. While this explanation might paint a better picture of universal VBM, it does highlight a broader challenge of improving representation in primary electorates.

Universal VBM worsened the turnout gap for in-person voters within Los Angeles in the March 2020 primary

SOURCE: Political Data Inc. (California voter registration file)

NOTE: (*) statistically significant at two-tailed 95 percent confidence level.

The Impact of Limiting In-Person Options

In our analysis so far, we have explored the effects of reforms to mail-in ballot policy, but California also experimented with different in-person options during the pandemic. Compared to the 2016 presidential election when just 2 counties had limited in-person options, 39 counties newly consolidated their precincts and offered a few days of early voting to compensate. Consolidating in-person options might have made voting more challenging for underrepresented groups in particular, independent of the other policy changes occurring at the same time.

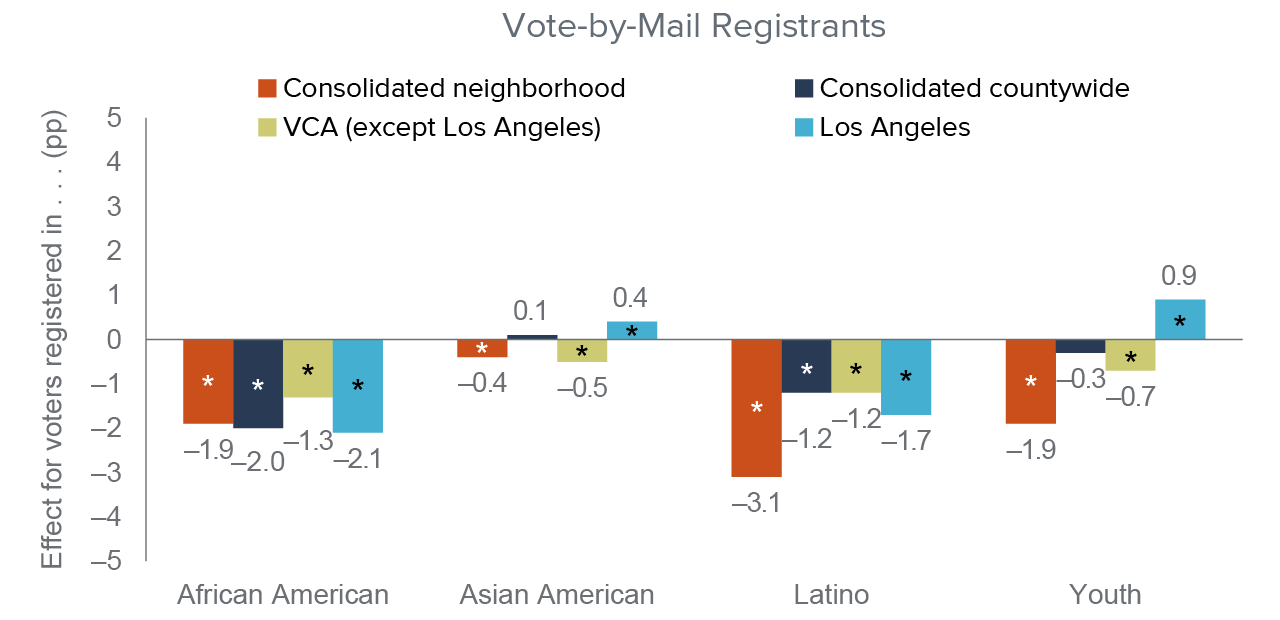

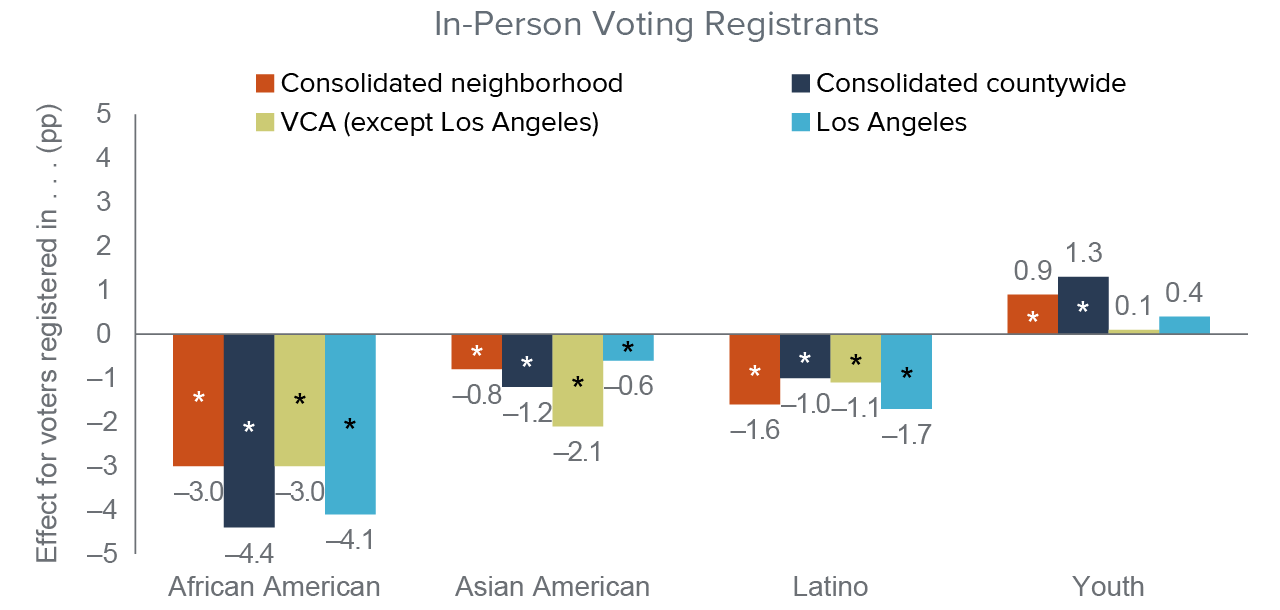

Figure 4 shows how the three options for consolidating in-person voting—consolidation with only neighborhood access, consolidation with countywide access, and the Voter’s Choice Act—affected turnout among demographic groups for voters who registered to vote by mail. Figure 5 shows the effect among those who registered to vote in person. Because Los Angeles County is so large and contains such a substantial share of the state’s communities of color, we have also separated LA County from the other VCA counties for this analysis.

We separately analyze VBM and in-person registrants because in-person registrants faced the greatest potential disruption from precinct consolidation: they were new to mail voting and might have planned to drop off their ballot in person. Yet VBM registrants also had the option to drop off their ballots in person; the main difference was the number who likely planned to take this approach and their comfort with returning the ballot a different way instead. (Technical Appendix B offers details of the methodology behind these numbers)

The results indicate that consolidating voting options worsened the turnout gaps for African American and Latino registrants. In fact, every consolidation approach worsened those gaps. The negative effects for in-person African American registrants were especially large, ranging from 3.0 to 4.4 percentage points, but the gaps were also larger for VBM registrants by between 1.3 and 2.1 percentage points. The negative effects on the Latino turnout gap were generally smaller: between 1.2 and 3.1 percentage points for VBM registrants, and between 1.0 and 1.7 percentage points for in-person registrants.

The effects are more ambiguous for Asian Americans and young people. There is little effect on the Asian American gap for VBM registrants: the effects flip from positive to negative for different consolidation approaches, and never exceed 0.5 percentage points in either direction. But the effects are more consistently negative for in-person registrants, falling between a small negative effect for Asian American voters in Los Angeles (–0.6 percentage points) to a more substantial negative effect for Asian American voters in VCA counties outside LA (–2.1 points).

For young people the effects are generally small and sometimes notably positive, such as for young VBM registrants in LA (0.9 points), or for young in-person registrants in consolidated neighborhood (0.9 points) or consolidated countywide (1.3 points) systems. Consolidated neighborhood voting did have a notably negative effect for young VBM registrants (–1.9 points).

Consolidating in-person options widened the turnout gap for African Americans and Latinos registered for vote-by-mail

SOURCE: Political Data Inc. (California voter registration file)

NOTE: (*) statistically significant at two-tailed 95 percent confidence level.

Changing in-person options widened the turnout gap for African Americans and Latinos registered for in-person voting

SOURCE: Political Data Inc. (California voter registration file)

NOTE: (*) statistically significant at two-tailed 95 percent confidence level.

These increases in the turnout gap often stemmed from a drop in voter participation among communities of color. For African American voters, every consolidation approach either made no difference or lowered turnout. Turnout for African American VBM registrants was very slightly higher (0.6 percentage points) in LA, but 0.4 to 2.9 percentage points lower in other consolidation counties, while turnout for African American in-person registrants was between 1.0 and 4.9 percentage points lower across all consolidation counties.

For Latino voters, the consolidated neighborhood approach lowered turnout (–4.1 percentage points VBM; –2.7 percentage points for in-person), while VCA-style consolidation with countywide access generally had little effect (between –1.1 and 1.0 percentage points for VBM; between –0.9 and 0.9 percentage points for in-person).

Asian American voters (–1.4 percentage points for VBM; –1.9 percentage points for in-person) and young voters (–2.9 percentage points for VBM, –1.2 percentage points for in-person) both saw lower turnout in consolidated neighborhood counties, but little change in other types of counties.

It is important to note that the effects we report here are measured against an overall improvement in California’s turnout gaps in 2020, as visible in California’s improvement relative to other states in Figure 2. California’s gap shrank 3.0 percentage points for African Americans, 2.9 percentage points for Latinos, 1.8 percentage points for Asian Americans, and 3.2 percentage points for young people. Even consolidation counties sometimes saw a better turnout gap in 2020 when measured against the gap in 2016.

But the consolidation counties were worse than the counties that did not consolidate. That result suggests that in an election year with a worsening turnout gap, the consolidation counties would have gaps that were even wider than in counties that did not consolidate.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The administrative changes California adopted in 2020 responded to the urgency of the pandemic. Since then, the state has continued with the pandemic approach through several special elections and a statewide gubernatorial recall. More recently, the state has committed to permanently mailing all voters a ballot. Policymakers and advocates took pains to avoid adverse results for underrepresented communities with these recent changes, but success was not guaranteed. This report has sought to understand the effects of these changes on voting equity as the state travels farther down this path.

Universal VBM has either reduced the turnout gaps between under- and overrepresented groups or had little clear effect. It may have had the paradoxical effect of worsening turnout gaps in the primary election—not because it lowers turnout for voters of color and young people, but because it does not target these communities enough to overcome the special challenges of low-turnout elections.

Consolidating in-person voting options was more problematic. It not only expanded turnout gaps across the board for African Americans and Latinos, it often discouraged participation for each group by itself. Consolidation was especially disruptive for African American voters, but it sometimes limited Latino and Asian American participation as well.

Based on these findings, the state’s decision to continue mailing all voters a ballot, whether there is a pandemic or not, appears reasonable. While the larger turnout gap in primary elections is notable, the smaller gap in general elections positively impacts a larger voting electorate.

However, election officials will need to do more work to target underrepresented groups in primary elections. Without such targeting, neutral reforms that encourage more voting may unintentionally expand the turnout gap in such low-turnout contests.

California counties should also take another look at future approaches to precinct consolidation. The change appears to place an undue burden on communities of color. In 2020, the counties adopted consolidation to manage the challenges of conducting an election during a pandemic. When the pandemic is over, election officials should practice caution when considering any extension to this practice without substantive change.

The Voter’s Choice Act is a special case. Consolidating traditional neighborhood sites into fewer vote centers has always been a part of the VCA reform. But it has been difficult to measure how these vote centers have affected participation independent of the universal mail ballots that are also a part of the VCA package. We now have evidence that the independent effect of the consolidation is often negative for communities of color in particular. Thus, California policymakers may need to reevaluate the consolidation aspect of the VCA reform.

These findings suggest that election officials should make efforts to help mitigate or even counter negative effects from consolidation under the VCA. At a minimum, greater and more effective outreach to communities of color may help ensure that all voters participate to the fullest with the VCA in-person voting options.