This post is part of a series reflecting on California’s experience of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Two years into the pandemic, the social safety net has evolved in largely unexpected ways. The experience of the 2007–2009 Great Recession led state policymakers to expect increases in cash and food assistance caseloads even as available state funds decreased. Instead, California’s budget has been flush, and demand has been low. Quick federal responses also resulted in a bevy of credits and temporary expansions to unemployment insurance that together lowered poverty in 2020.

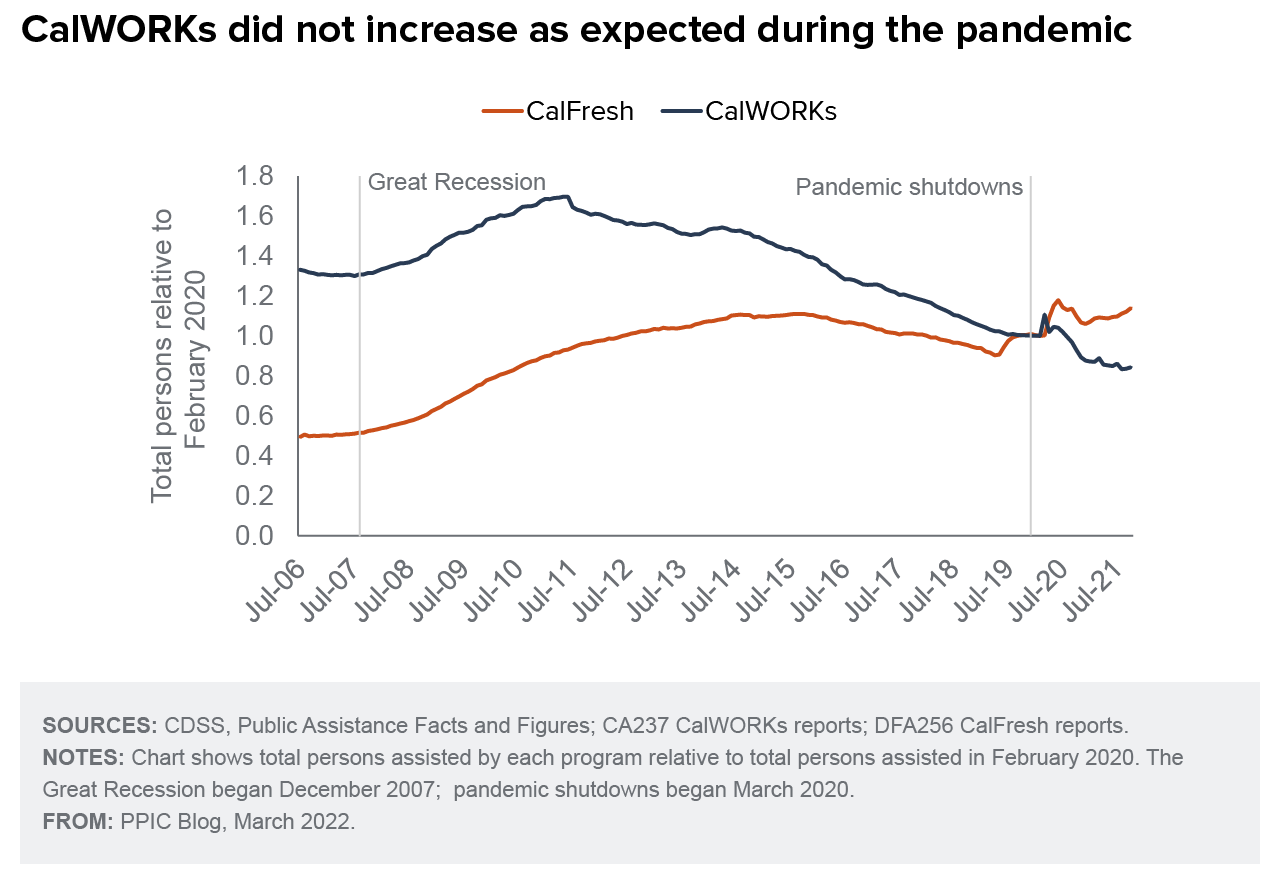

As the state shut down in March 2020, CalWORKs need was expected to increase, as it did in the last recession.

CalWORKs participation rose sharply as the state paused eligibility reviews in the early months of the pandemic. But participation soon dipped and then continued to decline—in stark contrast to the steady increase over many months after the Great Recession.

The CalFresh caseload also spiked then dipped, but rose again in fall 2020. A key factor behind the brief spikes may have been the temporary removal of paperwork hurdles, while the decline may be due in part to federal stimulus payments and unemployment insurance (UI) expansions lowering need.

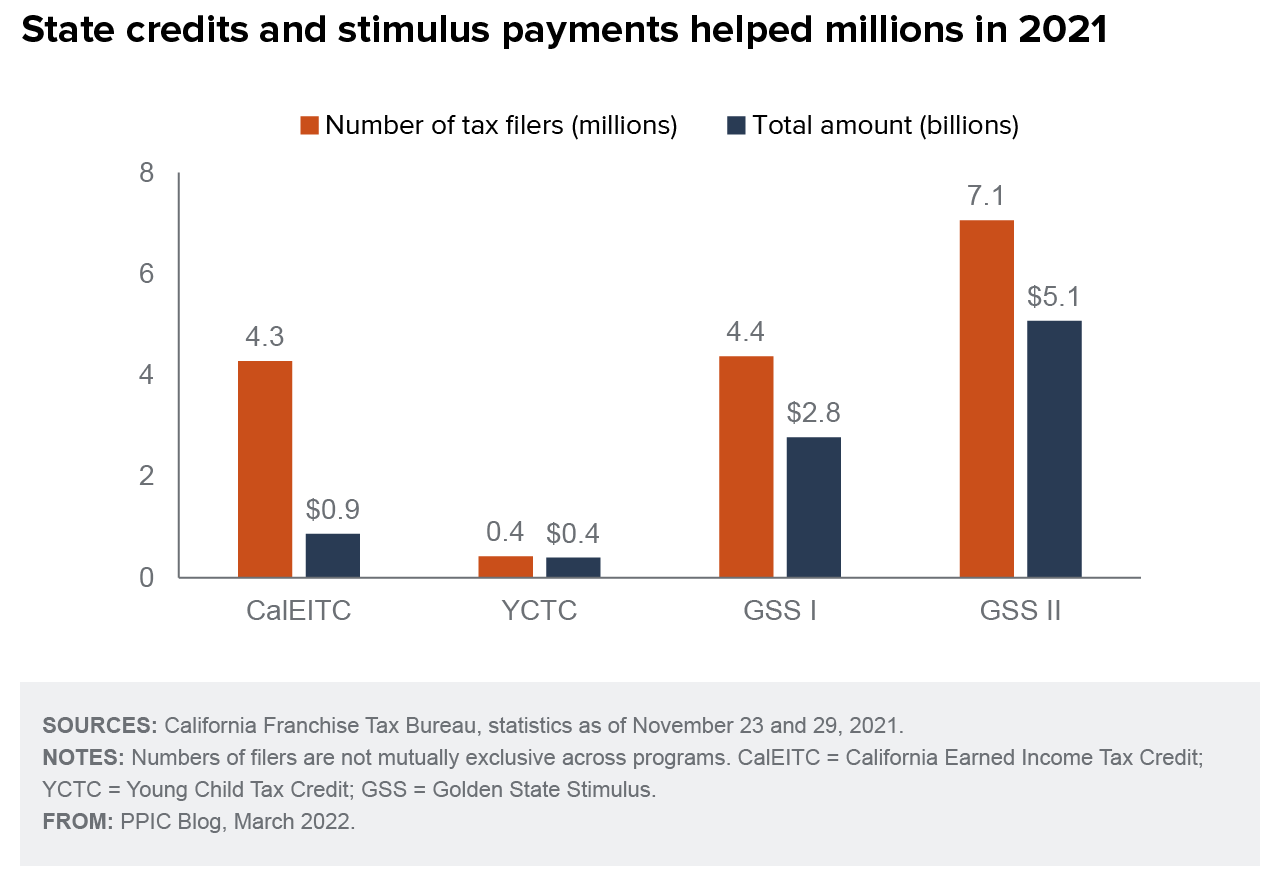

Tax-based stimulus payments and credits expanded in 2021.

Under President Trump, the federal government took rapid action with traditional federal stimulus payments, known as Economic Impact Payments (EIP), which were distributed in spring 2020. A second set of payments followed in early 2021. To receive the payments, families needed to file taxes and have a Social Security number (SSN).

In March 2021, the new Biden administration added a third EIP and a temporary expansion of the Child Tax Credit that provided monthly payments and was available to those without earned income. Children with SSNs were eligible even if tax filers lacked an SSN.

To address the exclusion of filers with an Individual Taxpayer Identification Number (ITIN)—often undocumented immigrant taxpayers—from federal stimulus, California policymakers provided $75 million for approximately 150,000 Disaster Relief Assistance for Immigrants (DRAI) payments. Although these payments fell short of need, certain state stimulus payments and tax credits were expanded in 2021 to include ITIN filers, and together provided about $9 billion to California tax filers.

It’s noteworthy that state stimulus payments also included Golden State Grants (GSG), dispersed in spring and fall 2021 to those receiving CalWORKs or Supplemental Security Income (SSI/SSP)—addressing another type of gap in tax-based stimulus. Recipients of safety net programs are less likely to file taxes than other Californians.

Food assistance programs also innovated.

During the pandemic-induced recession, CalFresh recipients with lower benefits saw an increase under the Trump administration. The Biden administration later took both short- and long-term steps to increase benefits for all participants.

With the shutdowns, the federal government reduced hurdles to CalFresh access through a number of temporary changes. California also applied for waivers to federal rules and participated in a federal pilot program in which CalFresh participants could purchase groceries online.

School nutrition programs were able to distribute meals outside of school cafeterias when public school closures became widespread. The overall number of meals provided to students fell in 2020 and during the 2020–21 school year, but meals were universally available: students were not required to document eligibility. This change has continued under federal law in 2021–22, and California plans to continue it after federal support for universal school meals ends.

To address the meals gap, students who had completed paperwork for free or reduced price meals under pre-pandemic guidelines could get pandemic Electronic Benefit Transfer (P-EBT) cards to replace some of the meals they missed—expanding the model of a successful summer EBT pilot from before the pandemic.

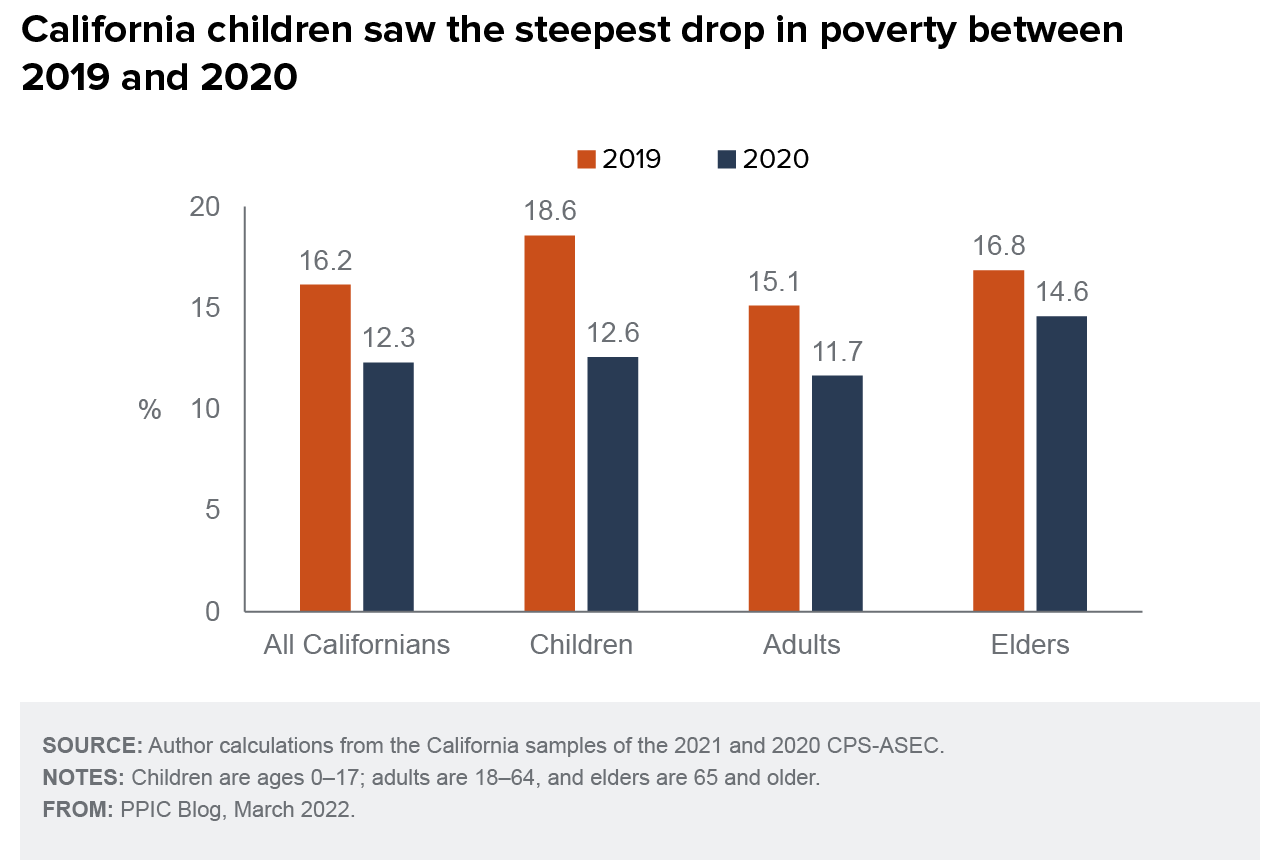

Temporary provisions lowered poverty substantially.

Poverty fell in California between 2019 and 2020 when we account for resources from safety net programs, despite severe disruptions to jobs and child care caused by pandemic shutdowns. Major factors were the federal economic impact payments and expanded unemployment insurance benefits.

The 2021 federal Advance Child Tax Credit likely lowered poverty for children and their families. However, the 2020 and 2021 measures were temporary and have been pulled back or not renewed. Although jobs continue to be the largest source of family resources, the sobering reality is that poverty is likely to be higher in 2022 than during the worst of the pandemic.

Lessons learned from the pandemic.

Stimulus payments, unemployment insurance, and other pandemic relief programs were short-term fixes designed to avert economic hardship amid a crisis. While federal actions sharply reduced poverty—and California actions reduced poverty even further—several of these fixes have expired or will expire at the end of the public health emergency.

Innovations sparked by the pandemic may offer long-term promise for a social safety net that can be universally accessible when Californians need it, although the scale of safety net programs remain a focus of debate.