California’s K–12 school facilities require significant new and ongoing investments to address aging infrastructure, changes in educational programs, and federal and state regulations. Maintenance, modernization, and new construction costs at the state and local levels are projected to exceed $100 billion over the next decade. A recent report by the California State Auditor estimates that the state will need to provide $7.4 billion in additional funding to meet modernization needs over the next five years.

Funding for facilities comes mostly from local sources and depends on local property wealth. The state provides some funding through the School Facility Program (SFP), but many have noted that the SFP’s local matching-funds requirement and first-come, first-served approach privilege wealthier districts with greater administrative capacity. By contrast, most funding for school operations comes from a state funding formula that is keyed to the shares of low-income students, English Learners, and foster youth in each of California’s 1,000-plus districts.

SFP funding is generated by statewide general obligation bonds, which must be approved by voters. This adds an element of uncertainty: the current bond (approved in 2016) is expected to be exhausted by 2022–23, but voters rejected a 2020 bond that would have provided $15 billion in SFP funding. Two new bonds are pending in the legislature, and the governor’s 2022–23 budget proposes $1.3 billion in one-time SFP funding. A better understanding of how SFP funding is distributed can help state policymakers address facility needs more equitably and efficiently.

How has SFP funding been distributed across the state?

The SFP was established by the state legislature in 1998 to provide matching grants for school districts to acquire school sites, construct new facilities, and modernize existing facilities. New construction grants require districts to cover 50 percent of project costs, and modernization grants require 40 percent of project costs to be covered locally.

Districts cover their shares primarily through local general obligation bonds and developer fees (levied on most forms of new development). Districts that cannot cover their share of project costs can apply for financial hardship assistance. In limited circumstances (such as natural disasters or severe health and safety threats), districts can get facility hardship grants.

Capital spending is higher in more-affluent school districts (in California and across the nation)—largely because of the link between bond funding and local property wealth. Ideally, state funding would narrow spending gaps by aiding districts with smaller local tax bases and/or less ability to fund facility projects. But the SFP modernization program appears to have exacerbated rather than mitigated funding disparities by district wealth—and by student subgroup. The reliance on matching grants, the first-come, first-served allocations—which benefit districts with more administrative resources—and the relatively small amount of hardship funding all appear to contribute to these gaps.

Analyses of school-level SFP allocations indicate that districts distribute their SFP funding in a relatively equitable way: most notably, they target schools with lower-income and Latino students. But this targeting mostly has a small impact, and districts have a limited ability to be more or less progressive in distributing their facility funding. This suggests that efforts to augment which districts receive SFP funding may be more effective than efforts to influence which schools within districts get funding for facility improvements.

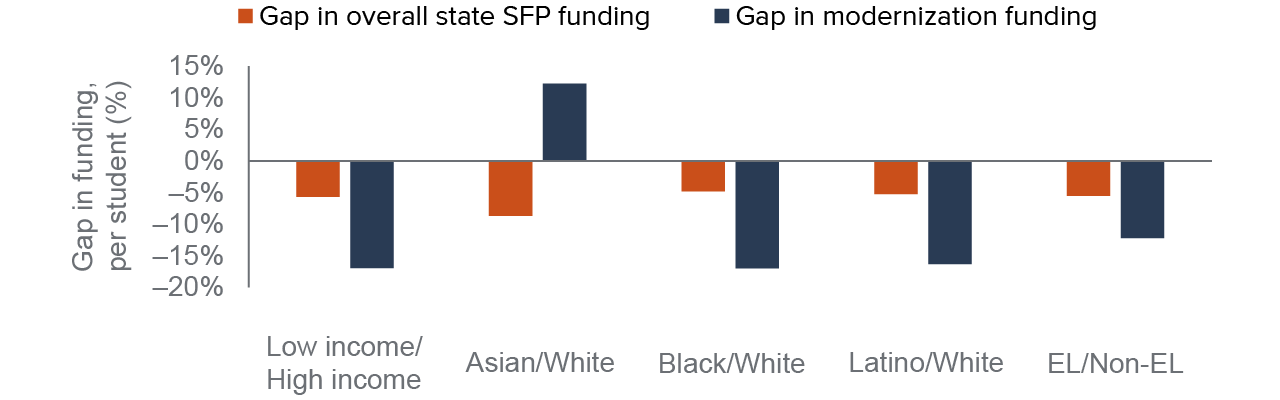

There are notable gaps in SFP modernization funding by student income, race/ethnicity, and language status

SOURCES: DGS SFP Project Audit Records; California Department of Education; authors’ calculations.

NOTES: Adapted from Figures 1 and 2 in the full report. Figure shows the difference in both total state SFP funding and modernization funding on a per student basis across several demographic groups, from 1998–2021. Funding amounts are computed from district-level data, for all SFP projects that could be matched to a district (whether or not they could be matched to a specific school site). Funding amounts are inflation-adjusted to 2021 dollars using the CPI-U.

How can California improve the equity and efficiency of state facilities funding?

As policymakers explore ways to fund school facilities, they will need to identify consistent and equitable funding streams so that all students have access to safe and effective learning environments. We offer four linked recommendations:

- Improve equity in state capital funding allocations, particularly for modernization. Recently proposed changes to the mechanics of the program, such as a sliding scale for matching amounts based on local wealth and/or need, criteria for facility need, and greater funding for hardship cases could help improve overall equity.

- Improve data collection and reporting on facility conditions. The state should establish a statewide inventory of school facilities, with periodic conditions assessments. Comprehensive data collection on school facility age would be a good start; it could help the state predict need for SFP modernization funds.

- Consider mandating district facility master plans. Requiring districts to submit facility master plans that clearly and equitably prioritize remedying the worst conditions would go a long way toward improving the state’s ability to quantify and address facility needs.

- Provide technical assistance to districts. Technical assistance from the state and counties could help districts with fewer fiscal and organizational resources apply for and receive SFP funding. Many districts would need assistance from county offices of education and/or the California Department of Education if the state were to require them to submit more-rigorous facility assessments.