California adopted the Next Generation Science Standards (CA NGSS) in 2013, with the aim of improving scientific literacy and strengthening the global competitiveness of the state’s workforce. NGSS implementation has been uneven across grade levels and districts, but most districts were at least in the early stages of implementing the new standards by spring 2020, when the COVID-19 crisis began. At a virtual event earlier this week, PPIC researcher Maria Fay outlined a new report on the pandemic’s impact on science education and senior fellow Niu Gao moderated a panel discussion about how California can support equitable investments in science literacy moving forward.

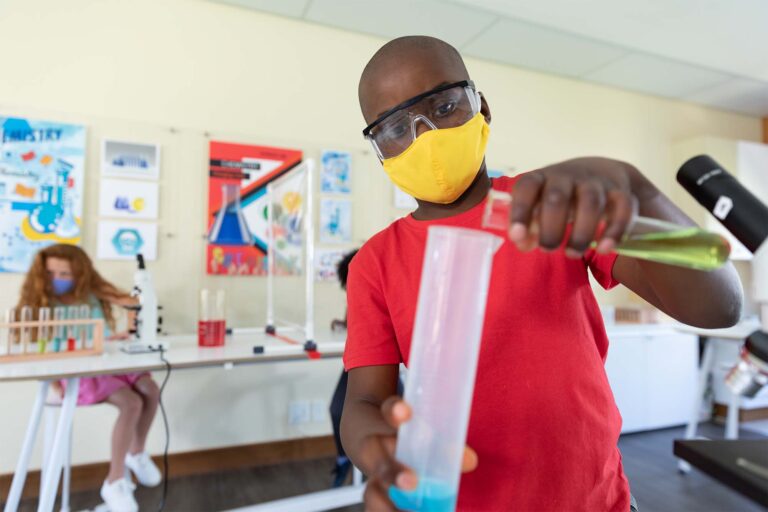

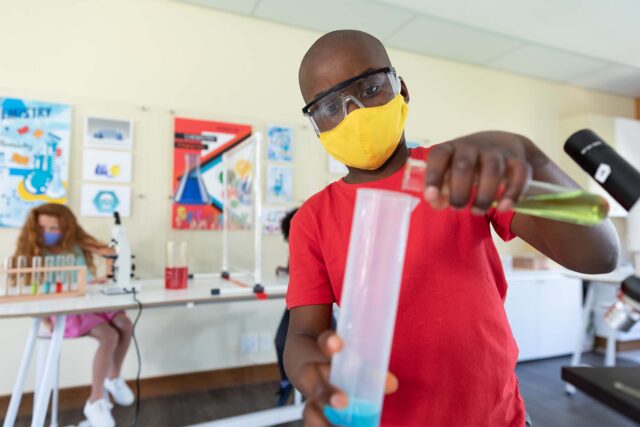

Fay noted that the new standards have the potential to boost science proficiency, which has long been low in California: “In 2015, only 24% of students in grades 4 and 8 were proficient in science, well below the national average, and there are large gaps based on race/ethnicity and family income.” During the pandemic, however, most districts focused more on math and English language arts (ELA), and most district recovery plans do not emphasize science.

Jennifer Bentley, education administrator at the California Department of Education, noted that science was not a top priority in most school districts before the pandemic. When schools had to shift abruptly to online instruction, she added, “uncertainty around teaching distance learning in general led a lot of teachers to pull back on content areas where they felt the least confident, and that included science.”

Martín Macías, superintendent of Golden Plains Unified School District, said that the pandemic did put the new science curriculum on hold in his rural district, “for a little bit.” But once schools had shifted to distance learning, the implementation process resumed. “For us it was just a matter of processing time,” he said.

While the pandemic brought many challenges and disruptions, it has also spurred investment and innovation. Bentley highlighted several recent state budget allocations: “The governor’s budget has a lot of opportunities for schools, districts, and county offices of education to take advantage of for science learning and professional learning, and instructional materials,” she said. In many cases, “it would just be a matter of allocating funds for science rather than ELA or math.”

For Superintendent Macías, a key sign of progress is the move to align science education with state frameworks across multiple subject areas. Literacy is particularly important in his district, where 88% of students are classified as English Learners at some point in their enrollment. With this kind of alignment, he added, “teachers can look at reading and literacy and writing in science, whereas we used to see things in siloes.”

While the panelists are hopeful, they agreed that systemwide change won’t happen overnight. “The education ship is a very large ship to turn,” said Heidi Schweingruber, director of the Board on Science Education at the National Academy of Sciences. “I actually think there’s more potential right now in the K–5 band for exploring deep, meaningful integration, just because of the structure of the school day. We need to think about how to do it in high school in a meaningful way. But I think there are places where exciting things are happening and we can use those as models.”

This research was supported with funding from the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 2128789. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.