This commentary was published by Zocalo Public Square on October 6, 2022.

In my 15 years researching and working in K–12 education, I haven’t seen anything like the COVID-19 pandemic disruption to education. This is especially true in rural areas, whose remote location, lower population density, higher poverty rates, and limited access to internet infrastructure and health care made their schools especially vulnerable during the pandemic—and where many students were already struggling before the pandemic.

But in parts of rural California, the pandemic also revealed silver linings. Some far-flung schools and districts in our state have made great strides bridging the digital divide, addressing teacher shortages, and supporting English learners.

Recent test scores from the 2022 National Educational Progress Assessment—the nation’s report card for K–12 schools—show just how much damage the COVID-19 pandemic and related school closures wreaked on learning. Average test scores for 9-year-old students declined seven points in math and five points in reading, wiping out nearly two decades of progress. Among Black students, average math scores fell 13 points.

But scores don’t provide the full picture. As the 2021–22 school year began, a mental health crisis was taking hold among students, too. More than a third of high school students nationwide reported experiencing poor mental health during the pandemic, and nearly half felt persistently sad or hopeless. Students in rural areas had higher levels of anxiety and depression, partially due to limited access to care.

These declines in academic learning and social-emotional wellbeing underline the need to improve school conditions and accelerate student learning throughout the nation. We do not yet have test scores for California students, but we know student needs are acute, particularly in rural areas.

The state’s rural schools faced unique challenges during each phase of the pandemic.

In what we are calling the first phase of the pandemic, in spring 2020, they struggled on the wrong side of the digital divide. Multiple barriers hinder broadband access and deployment in rural areas. Many internet service providers do not find it profitable to serve rural areas, where low population density makes it costlier to build and maintain internet infrastructure. Making broadband affordable for rural households is also a formidable challenge. Studies show higher poverty rates in non-metro areas across the US.

For this reason, the abrupt shift to distance learning in spring 2020 left many rural schools in California scrambling for solutions. In 2017, 74% of California households had access to broadband, with access slightly lower—70%—among rural households. But this gap grew markedly over time. In 2019, 84% of California households had broadband, compared to 73% of rural households. More than one in four rural households still did not have high speed internet when the pandemic hit late in the year. Without reliable internet, students cannot access curriculum, receive live instruction from teachers, complete assignments, or receive academic supports.

During the second phase of COVID, in fall 2020, fluctuating enrollments destabilized rural schools. In California, K–12 enrollment statewide declined by nearly 3% between the 2019–2020 and 2020–2021 school years. Some rural counties experienced an exaggerated version of this trend; enrollment fell 10% in Humboldt, Mono, and Inyo Counties. But other rural counties gained students, bucking the statewide trend and placing greater demands on district resources. Alpine, Amador, Calaveras, El Dorado, Sierra, and Sutter counties experienced double-digit growth, with enrollment increasing 17%, for example, in El Dorado.

Statewide enrollment dropped another 1.8% in 2021-2022 but counties like El Dorado, Calaveras, and Tuolumne continued to experience growth—1.7%, 4.5% and 3.3%, respectively. Because state funding is linked to student enrollment, declines pose significant challenges for districts—but increases create problems too. Rural districts, which have long struggled to recruit and retain quality teachers, had trouble keeping up with growing enrollment. About a quarter of rural schools nationwide were understaffed prior to the start of the pandemic, and 70% said there were too few candidates applying for open teaching positions for the 2022-23 school year.

And in the third phase of COVID, as caseloads declined and California started to emerge from the pandemic in spring 2021, rural schools brought students back for in-person instruction earlier than schools in other parts of the state, in large part because providing online instruction had been so difficult. Nationwide, 63% of rural schools offered in-person instruction to all students in January 2021, compared to only 35% of urban schools. Rural districts in California reopened to all grades in early February 2021, while urban districts fully reopened in early May.

As we worked with rural schools during COVID, we also saw hints of progress.

Lindsay Unified, a small, low-income Central Valley district with 4,000 students, is successfully addressing teacher shortages through a “grow your own” approach. In 2016, the district launched a community Wi-Fi network and shifted some of its curriculum online to facilitate personalized learning. It also created a program to recruit teachers and staff, urging students to attend college on loans that would be forgiven if they returned and taught in Lindsay schools for five years. This past year, the district added a residency program to help teachers earn a master’s degree and teaching credential in one year.

In California’s southernmost reaches, the Imperial County Office of Education (ICOE) has worked with local organizations and agencies for more than 20 years to build and maintain a state-of-the-art fiber-optic communications network for its K–12 schools. In 2018, it launched BorderLink to bridge the homework gap by expanding affordable access to reliable internet at home. ICOE was relatively well positioned when the pandemic hit to connect students to distance learning. Today the county is leveraging pandemic related stimulus money to upgrade equipment and expand capacity further.

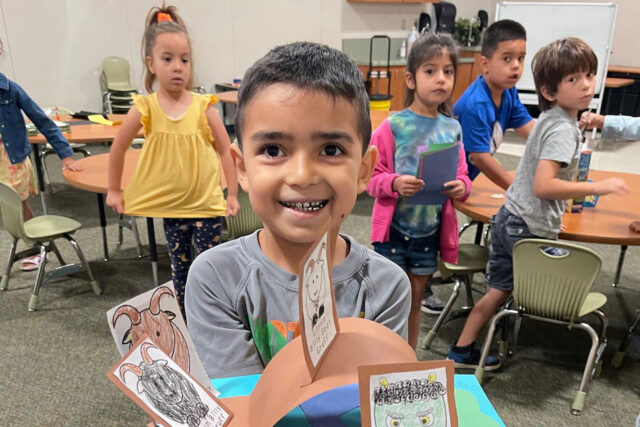

Finally, during the pandemic, the Golden Plains district, which serves mostly English learners, used science content to enhance English language arts and English language development instruction. This integrated approach ensures that science learning and language development occur simultaneously. Before it was in place, English proficiency was a barrier for students to access science learning.

The pandemic has had a profound impact on all students’ academic and social-emotional wellbeing, and in response, school districts have enacted strategies to support learning recovery and improve student social-emotional wellbeing. It makes sense to acknowledging the special hurdles far-flung districts face.

Fortunately, state and federal governments are providing investments toward rural schools. In 2021, California allocated more than $6 billion to expand broadband infrastructure. Three rounds of federal funding provided more than $21 billion to California schools to support recovery and renewal, including funding for after school programs at rural schools. Spent on equitable, evidence-based programs, these investments can help rural schools accelerate student learning, address mental health needs, and keep up with the demands of 21st century education.