- Preschool improves outcomes.

High-quality preschool improves short- and long-term outcomes such as school readiness, high school graduation, and earnings—although some early educational advantages can fade. There are some indications that low-income children benefit more than their wealthier peers from access to free, high-quality preschool. In addition, universal preschool programs, which enroll children from all socioeconomic backgrounds, may improve outcomes for low-income children more substantially than income-targeted programs. - Child care supports parental employment—and most parents of young children work.

In California, 77% of working-age parents (and other caregivers) of preschool-aged children are employed at least part time. At least one adult works outside the home in 98% of families with two (or more) working-age adults; in 55% of these families, all adults work. Among single-parent families, 86% of parents work. Different employment rates among single-parent families may partly reflect lack of access to high-quality affordable child care. Single-parent families with young children have strikingly high poverty rates: 62% of preschool-aged children with just one working-age adult at home lived in or near poverty. - State and federal dollars support several preschool programs in California.

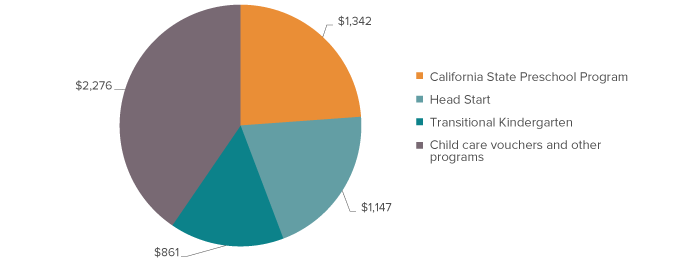

California has three main publicly funded preschool programs—the California State Preschool Program (CSPP), Head Start, and Transitional Kindergarten. Other publicly funded programs serve a broader age range, typically ages 0-12, by providing vouchers for some low-income working families to obtain care. CSPP serves low-income families (earning less than $54,000 for a family of 3) with both part-day and full-day care, prioritizing employed parents for the latter. Head Start serves families with incomes under the federal poverty line ($21,000 for a family of 3). Transitional Kindergarten has no income requirements, but enrolls only a limited age group. For FY 2019, the state budgeted $2.2 billion for CSPP and Transitional Kindergarten; the federal government provided $1.1 billion for Head Start for children ages 0-5. Spending on these three programs covers over half of public expenditures on child care and development in California.

Preschool programs account for over half of state and federal spending on child care in California

SOURCES: Legislative Analyst’s Office, Child Care and Preschool Budget; US Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Justification of Estimates for Appropriations Committees, FY 2019.

NOTES: Dollar values are presented in millions for FY 2019. Child care vouchers and other programs for children under 13 include the Alternative Payment Programs, General Child Care and Development, migrant programs, the Bridge program for foster children, and care for children with severe disabilities. About a third of Head Start enrollment is children ages 0–2. This chart excludes funding for Title I district preschool and special education infant, toddler, and preschool programs, which blend federal, state, and local funds and are administered locally; Melnick, et al. (2017) estimate that they received $245 million in state and federal funds in 2014–15. Transitional Kindergarten can also receive additional, local funding, which is not reflected in this chart.

- Public preschool programs lack capacity to serve all eligible children.

Together, CSPP and Transitional Kindergarten have 260,000 funded slots for 2018–19; Head Start had about 70,000 funded preschool slots for 2017–18. Limited data sharing between local, state, and federal programs complicates the ability to get accurate counts of actual enrollment—as a result, measurements of unmet need are not exact. However, one estimate finds that the largest programs enrolled 38% of eligible three-year-olds and 69% of eligible four-year-olds in 2015–16. - Preschool enrollment reflects social and economic disparities.

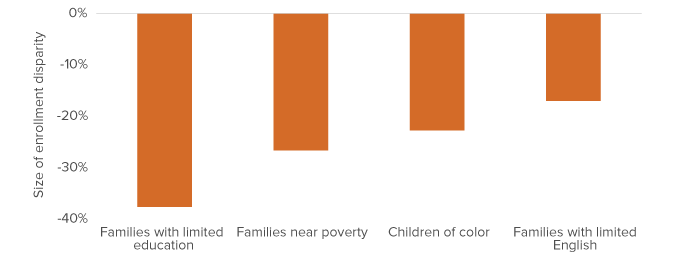

California’s population includes slightly more than one million three- and four-year-olds. Families reported in 2016 that 35% of their three-year-olds and 56% of their four-year-olds were enrolled in either a private or public preschool. Preschool-aged children are much less likely to be enrolled in preschool if no adult in the family has a college degree (37% vs. 59%); they are somewhat less likely to be enrolled if their families live in or near poverty (38% vs. 52%), or if no adult speaks English well (39% vs. 47%). In addition, children of color are less likely to be enrolled than white, non-Latino children (42% vs. 55%).

Children who face disadvantage tend to have lower enrollment in preschool

SOURCE: Estimates from the 2014–2016 California Poverty Measure (CPM) and American Community Survey (ACS) data.

NOTES: Chart shows the percent difference for each group’s enrollment in preschool or nursery school relative to that of preschool-aged children not in the group. Negative numbers indicate relative under enrollment among those in the indicated group. Families with limited education refers to those in which no one has a four-year college degree; children of color refers to those not identified as non-Latino white; families near poverty are those with resources under 150% of the CPM poverty line; families with limited English are those in which no adult reports speaking only English or speaking English very well.

- Expanding access to preschool will require a multipronged approach.

In his 2019–20 budget proposal, the governor recommended spending on workforce development, kindergarten infrastructure, and full-day CSPP slots. Together, these proposals promise to increase access to preschool. Nationally, the states with the highest levels of state preschool participation enroll more than 70% of all four-year-olds. To reach these levels, California will need to reckon seriously with existing program fragmentation. Decision makers may also want to consider how to expand—by building on universal public school, or by growing targeted programs.